This phrase I understand: “Love you, too!” (Meaning: “Love you, also.”)

And yes, I grasp the vaguer meaning of this phrase: “Love you two.” (As in: “I love John first, but I love you two”).

But now, consider the curious phrase: “Love you to…” — It’s a quandary! It’s an unfinished preposition waiting for a following noun. (As in: “Love you to death!” or “Love you to pieces!” or “Love you to the end of time!”)

Or… it could be an unfinished infinitive waiting for a following verb. (As in: “Love you to love me.” Or “Love you to listen.” Or “Love you to comprehend what I’m saying”).

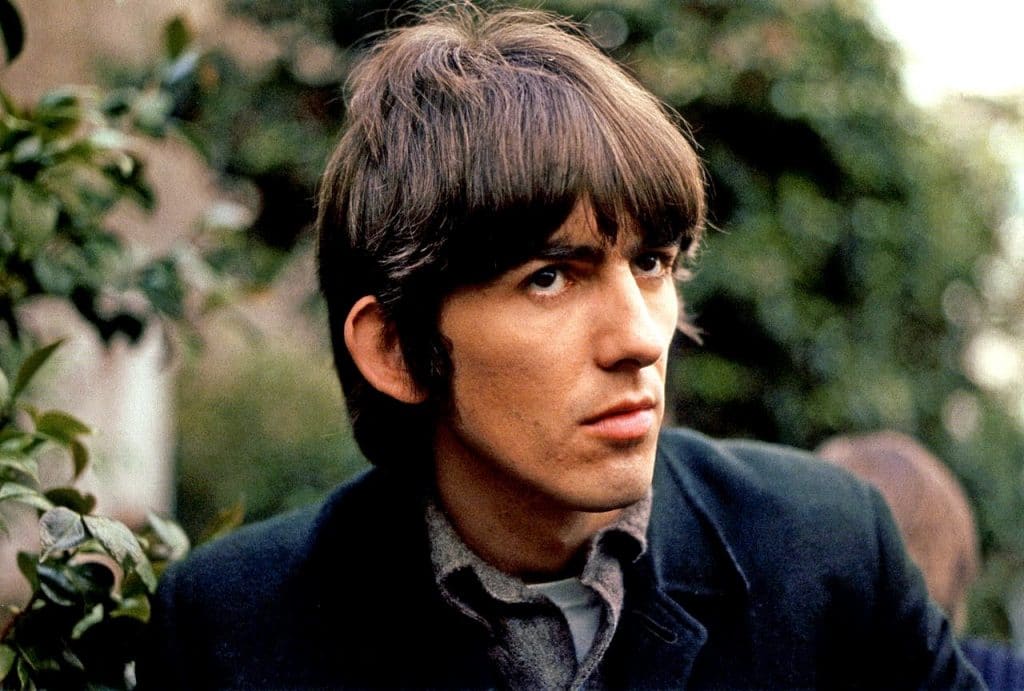

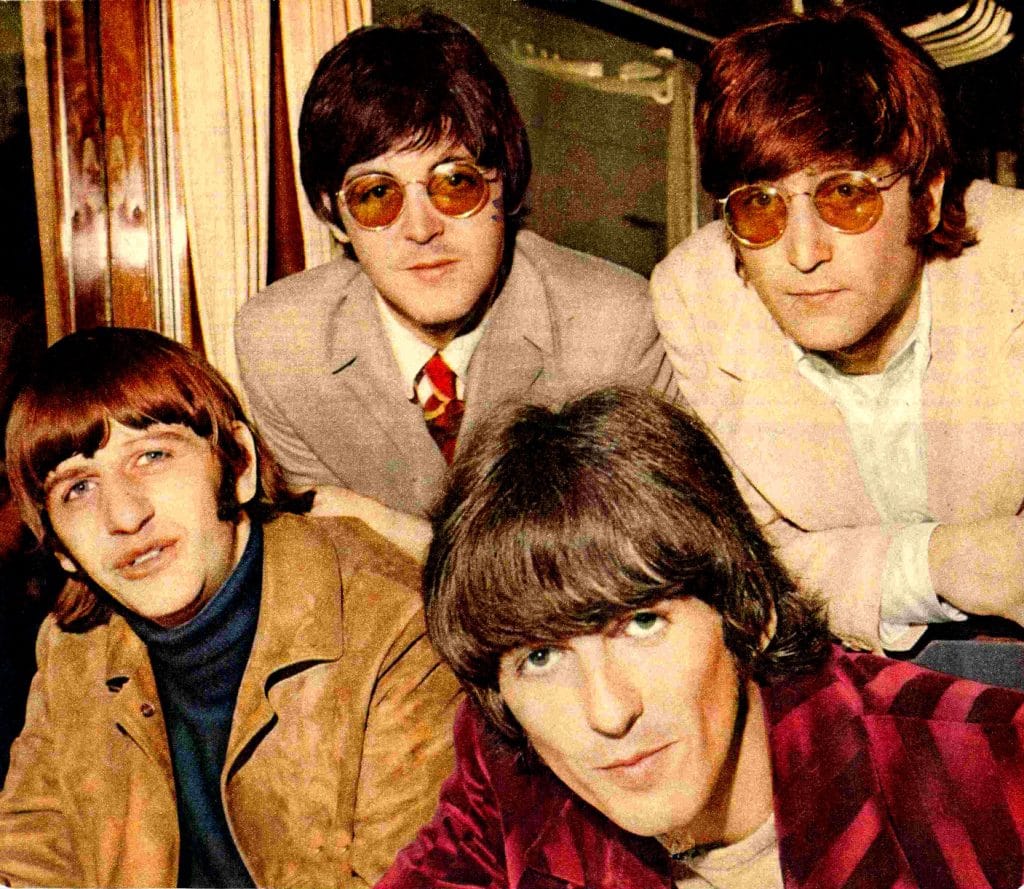

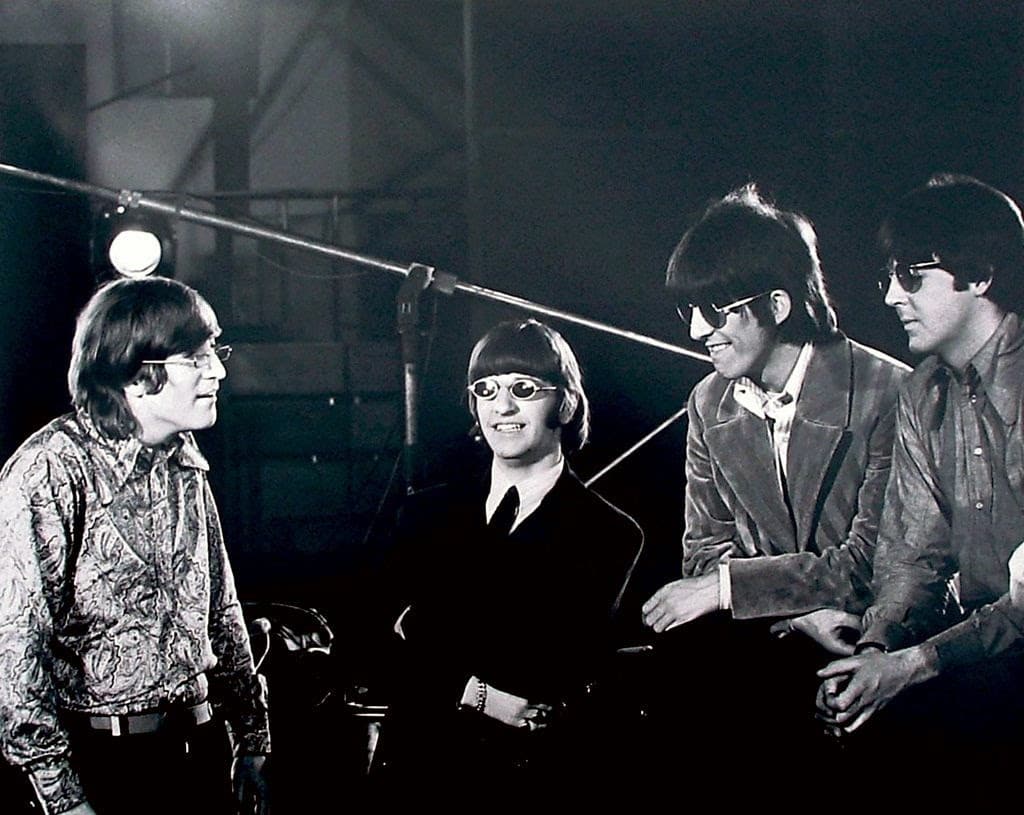

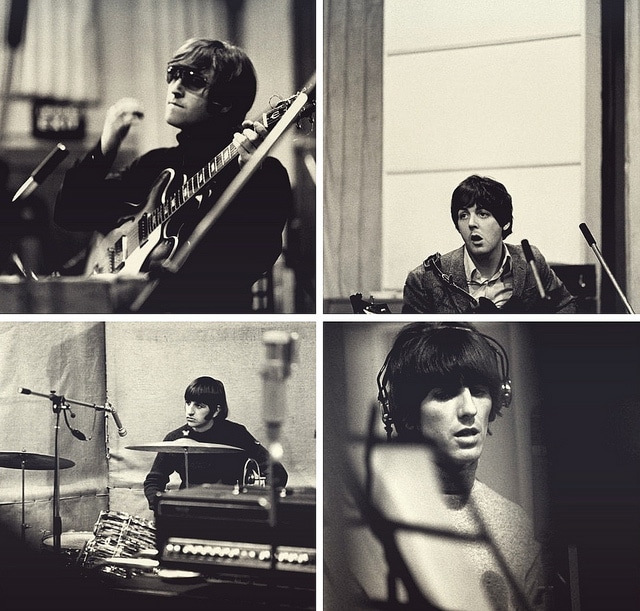

But as George Harrison’s title stands – without any other nouns, verbs, or explanations to complete it – the phrase is incomplete, unclear, and ambiguous. And really, that is where George Harrison was when he penned this 1966 song. Recently returned from a trip to India where he had begun sitar studies under Ravi Shankar and the study of the Hindu religion, George was an excited newbie. He was completely enthusiastic, but green – an amazed young man muddling through the murky waters of a complex, new faith and an equally complex mode of musical expression. George was a bit overcome.

Recently married to Pattie Boyd, George wanted to make this song a love ballad for his wife. He really did! But the tenets of his new faith kept pulling at him, sternly reminding him that:

A lifetime is so short,

A new one can’t be bought…

The brevity of existence kept bothering George, niggling at him – and those beliefs transformed his love song into a serious warning refrain: a song about living not only for today, but also living a life worthy of the hereafter.

George tried to shrug off his feelings of impending doom: of death at his back, of time running out, of life slipping away, but in “Love You To,” he failed to escape that weighty influence. Even when employing his famous, droll Harrison humor to minimize the song’s grim overtones, the boy’s wit was still dark:

Love me while you can,

Before I’m a dead old man!

he said. Despite his best efforts, George’s love song kept slipping into a sermon. No matter what George tried to say (or sing), his bride’s ballad kept circling back around to one all-important message: Life is short; time is limited; live prudently! Or in George’s adaptation:

Each day just goes so fast

I turn around, it’s past…

It was a bit depressing. As the song neared its close, George struggled to find something to smile about, to celebrate.

Well, a bit before The Beatles’ time – when the poets of the Middle Ages felt death pressing down upon them, they decided that the wisest thing to do was to carpe diem…to “seize the moment!” They decided to make hay while the sun shines! To quote Medieval poet Robert Herrick’s words, “Gather ye rosebuds while you may!”

And in 1966, George reached the same conclusion. He decided the very same thing. At the end of his song, he advised Pattie (and all of us) to go for the gusto! To grab happiness while you can! To smile while you still have teeth!

Make love all day long!

Make love singing songs!

he advised us. It was the only viable solution to mortality that George could offer.

By The Summer of Love (1967) when George released “Within You, Without You” as the opener for Side 2 of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, both his faith and his acumen on the sitar had reached a higher plane. By then, he was able to speak with more depth and wisdom. But here on Revolver, George is clearly grappling with a vast belief system and an intricate musical genre, so he falls back on immediate gratification as a ready, easy solution.

Or maybe…maybe George’s answer was, in fact, the very best solution anyone could offer.

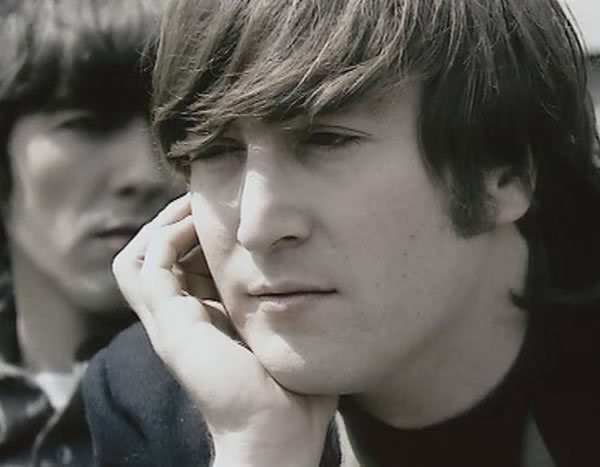

In 1967, John Lennon would so famously tell the world that, “Love is all you need.” And here, George is voicing the exact same sentiment. In light of death, aging, and fleeting existence, the youngest Beatle turns to Pattie and to us, advising everyone to cling tightly to love. Sage advice, I think. Perhaps our kid wasn’t such a newbie after all.

Jude Southerland Kessler is the author of the John Lennon Series: www.johnlennonseries.com

Jude is represented by 910 Public Relations — @910PubRel on Twitter and 910 Public Relations on Facebook.