Revolver

Side One, Track Three

“I’m Only Sleeping”…or So He Said!

by Jude Southerland Kessler, Don Jeffries, and Bob Wilson

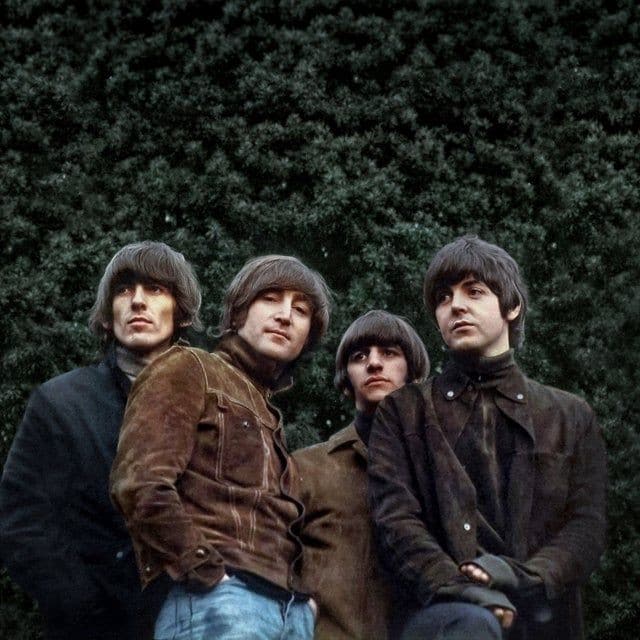

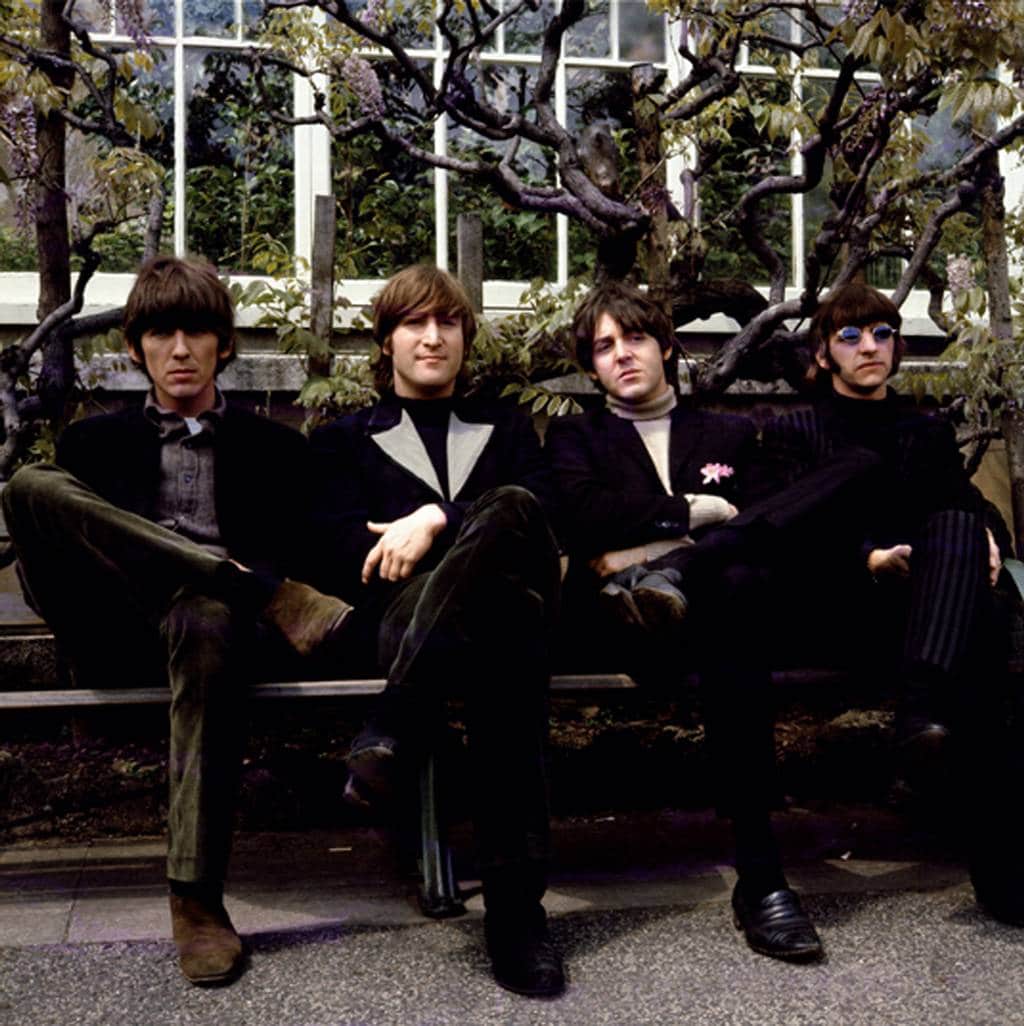

Through 2023, the Fest for Beatles Fans blog will explore the intricacies of The Beatles’ astounding 1966 LP, Revolver. This month, Don Jeffries and Bob Wilson of the fascinating new book on the “Paul is Dead” controversy, From Strawberry Fields to Abbey Road: A Billy Shears Story, join Jude Southerland Kessler, author of The John Lennon Series, for a fresh, new look at track three of this landmark LP.

What’s Standard:

Dates and Times Recorded, Studios Used:

27 April 1966 (Studio 3 from 11.30 p.m. – 1.00 a.m.)

29 April 1966 (Studio 3 from 5.00 p.m. – 1.00 a.m.)

5 May 1966 (Studio 3 from 9:30 p.m. – 3.00 a.m.)

6 May 1966 (Studio 2 from 2.30 p.m. – 1.00 a.m.)

Source: Lewisohn’s The Complete Beatles Chronicle and The Beatles Recording Sessions

Tech Team:

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald

Instrumentation and Musicians:

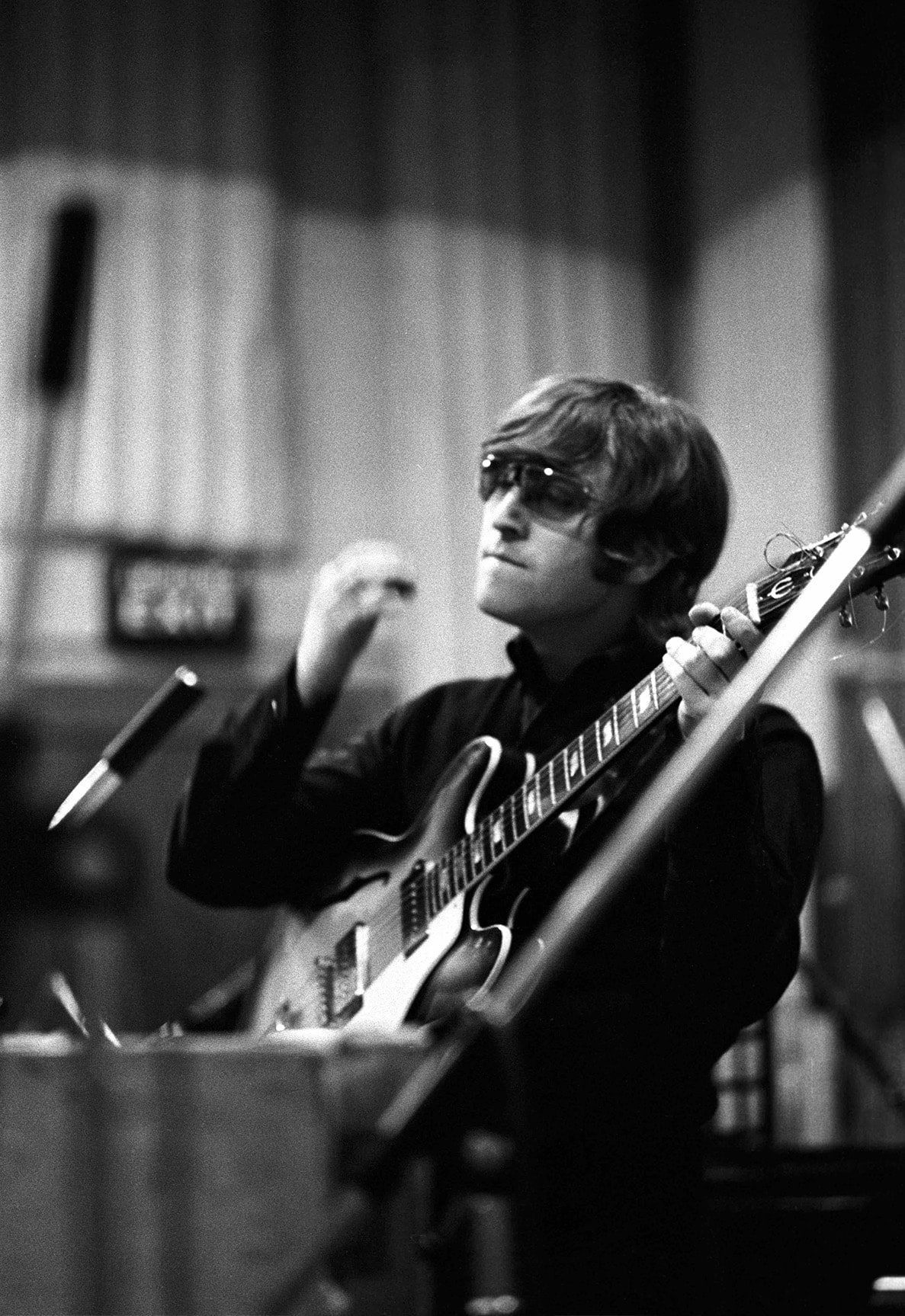

John Lennon, the composer, sings double-tracked lead vocals and plays acoustic guitar on his 1964 Gibson J-160E.

Paul McCartney sings harmony vocals and plays bass. Some sources claim he used his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass. Others, just as adamantly, state Paul used his Hofner. Rodriguez says the Hofner was used to get “those tiptoeing bass sounds.” In The Anthology, George Martin states that Paul played the lead line with George Harrison. In Here, There, and Everywhere, Geoff Emerick seconds this assertion. (p. 124)

George Harrison sings harmony vocals and plays lead guitar. However, no source, including Babiuk’s Beatles Gear, identifies the guitar Harrison was using for the dramatic “backwards” guitar solo. And if, as Martin and Emerick insist, Paul played lead simultaneously, we do not know what instrument Paul was employing either.

Ringo Starr plays his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set.

Sources: The Beatles, The Anthology, 211, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 219-220, Lewisohn, The Recording Sessions, 77-78, Emerick, Here, There, and Everywhere, 124, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 129-132, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 328-329, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 15 and 18, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 132-134, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 106, Mellers, Twilight of the Gods: The Music of The Beatles, 71-73, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 161, Riley, Tell Me Why, 185-186, O’Toole, Songs We Were Singing: Guided Tours Through The Beatles Lesser Known Tracks, 116-118, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 200, Davies, Beatles Lyrics, 150-153, Womack, Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, 129 and 139, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 180-182 and Cardinale, “The Spark of Inspiration” found at https://medium.com/synapticalchemy/the-spark-of-inspiration-2e51272d0dcd.

What’s Changed:

As Kenneth Womack perceptively observed in Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, “Where Rubber Soul is about The Beatles’ self-conscious redefinition of themselves and their art, Revolver is about taking those new-fangled models of themselves and their art out for a proverbial spin. This album is about revving up the engines of their musicality…about The Beatles’ desire to push the boundaries of their achievement, to experiment…” (p. 129)

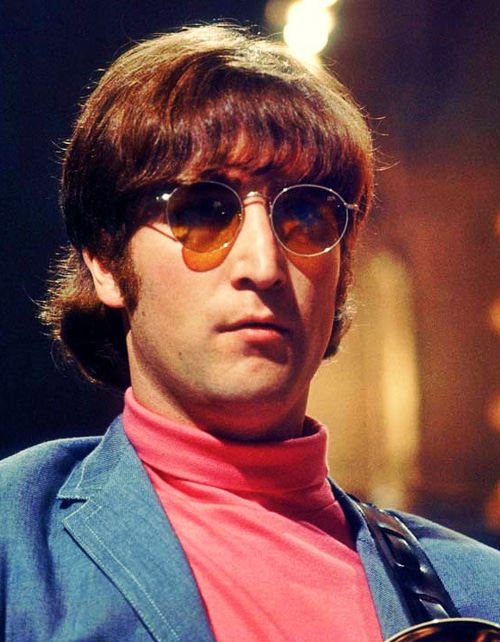

And experimentation is precisely what John Lennon is about here in “I’m Only Sleeping” as he cleverly recreates his favorite place: the enchanted world of sleep-inspiration, the birthplace of that cherished “spark of after-midnight.”

In his blog “The Spark of Inspiration,” Stephen Cardinale poetically observes: “The spark of inspiration is…a force that pulls you from your slumber and won’t allow you to rest until you’ve imprinted the ground with that spark from the heavens.” Very early on, John Lennon discovered and utilized this field of somnambulant stimulation, and throughout his career, he would credit it with the stimulus for songs such as “Across the Universe” and “Watching the Wheels.” In the slim space between wake and slumber, John encountered the shadowy land where (for him) great ideas exist.

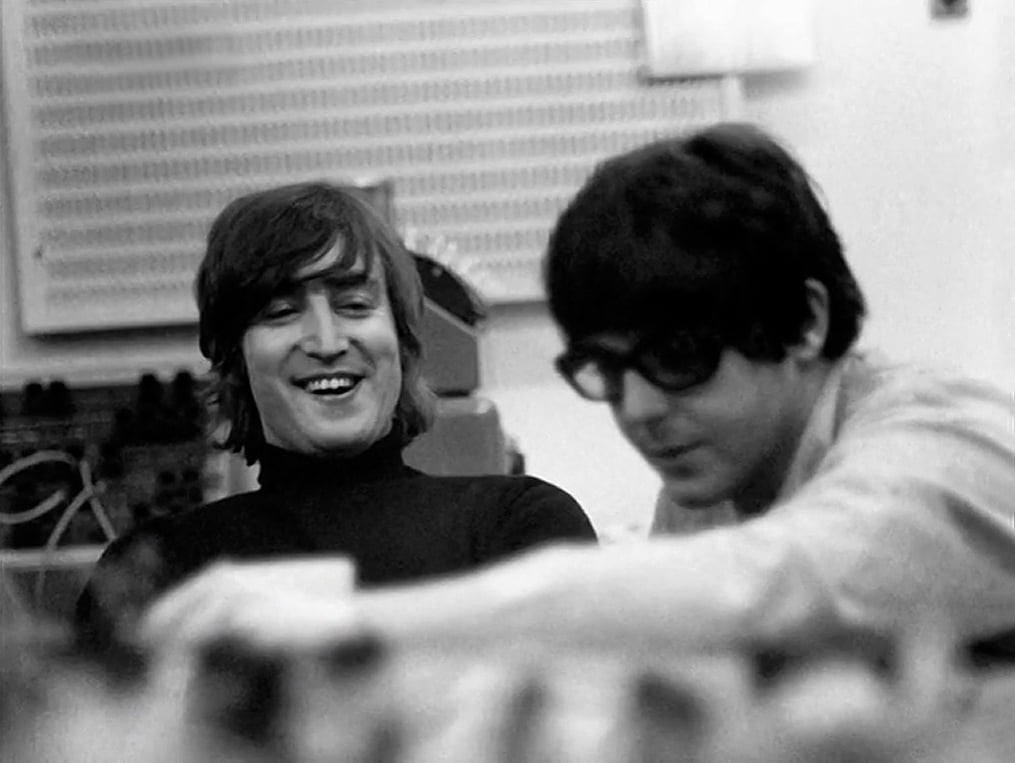

In “I’m Only Sleeping,” John utilizes every “bell and whistle” at his disposal to recreate the fertile fog of semi-consciousness. Calling upon the genius of The Beatles and the musical acumen of George Martin and Geoff Emerick to help him bring this world to life, Lennon employs sophisticated technical tricks – and a few simple ploys – to set an elaborate stage for us all…and to wave a welcoming hand toward his “Land of Nod.”

Robert Rodriguez, in Revolver, How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, states, “Just as when you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail, so it was in 1966: if you were a Beatle, every sound was fair game to be sped up, slowed down, turned backwards, doubled, and otherwise sliced and diced.” And here, John and the band do precisely that; they create extraordinary sound effects that pull us into Lennon’s exotic reality. These devices include:

- Frequency Modulation – On page 15 of That Magic Feeling, John C. Winn tells us, “On 27 April, The Beatles…taped 11 takes of John’s new composition, ‘I’m Only Sleeping.’ These were played in the key of Em, but with the tape running fast.” (At 56 cycles, Lewisohn tells us in The Beatles Recording Sessions, p. 76) “This gave the song a more languid, dreamy quality when played back” at normal speed, at 47¾ cycles, Lewisohn states. (The Beatles Recording Sessions, p. 76) The resulting exotic harmonies skew away from the harmonies of “This Boy.” They are equally lovely, but now also haunting.

Rodriguez explains that John’s vocal was recorded with the tape rolling more slowly than customary. (In The Beatles Recording Sessions, p. 77, Lewisohn tells us it ran at 45 cycles.) Then, when the tape proceeded at normal speed in playback mode, John’s voice became “more dreamlike,” more ethereal, and removed. (pp. 130-131)

The Beatles had become fascinated with frequency modulation in making “Rain.” And here it was carefully applied to veil John’s sleepy song in the drowsy cobweb of half-consciousness.

- Use of Backwards Tracks – The Beatles used 17 seconds of backward guitar in the body of “I’m Only Sleeping” and another ten seconds in the fade-out. That’s all. And to capture this beautifully bizarre sound, it took six hours of intense work. Geoff Emerick claims it was nine hours of labor (p. 124), and Hunter Davies, in The Beatles Lyrics, claims it took 12 hours. (p. 151) This may seem rather extravagant, but as Spignesi and Lewis state, when The Beatles “wanted an effect, they moved earth and sky to achieve it.” (p. 181) The curiously curling and writhing guitar is the essence of the sleep soundtrack: the stuff of dreams.

Here is how George Martin explained the “very strange” technique employed to achieve the sound: “In order to record the backward guitar on a track like ‘I’m Only Sleeping,’ you work out what your chord sequence is and write down the reverse order of the chords – as they are going to come up – so you can recognize them. You then learn to boogie around on that chord sequence, but you don’t really know what it’s going to sound like until it comes out again. It’s hit or miss, no doubt about it, but you do it a few times, and when you like what you hear, you keep it.” (Spignesi and Lewis, 180) That sounds logical – doable, even.

But in Here, There, and Everywhere, EMI Engineer Geoff Emerick claimed the process was “one hard day’s night!” (p. 124) He says it “turned out to be an interminable day of listening to the same eight bars played backwards over and over and over again.” (p. 124)

As mentioned earlier, Beatles scholars disagree about whether or not Paul joined George in playing the backwards line. But all agree that two guitar parts were recorded. In The Beatles Recording Sessions, Lewisohn says, “[The Beatles] made it doubly difficult by recording two guitar parts – one ordinary and one a fuzz guitar – which were superimposed on top of one another.” Similarly, O’Toole in Songs We Were Singing, states, “Martin…had to conduct Harrison beat by beat, with the guitarist ultimately recording two separate solos – one with fuzz effects or distortion, and one without. Martin then laid the tracks on top of one another…” However, Hammack in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2 says that “on May 5th, McCartney and Harrison added lead guitars to the song…The solos (one with fuzz distortion added) were recorded simultaneously.” One guitarist or two? We may never know definitively. But the artistry and care given to this song is just shy of miraculous.

- 3. Simple Sound Effects – Of course, not all of The Beatles’ “sound effects” in “I’m Only Sleeping” were groundbreaking. At 1:57 in the song, you can hear someone (presumably, John) say, “Yawn, Paul.” And at 2:01, Paul yawns. It’s not a highly complex maneuver, but it adds the perfect final touch in the recreation of John’s Muse-inhabited realm of sleep. And as O’Toole remarks, “…it represents [The Beatles] at their most experimental to date…nothing was off limits for this 1966 masterpiece.” (Songs We Were Singing, 116)

A Fresh New Look:

Don Jeffries is the author of myriad books including Bullyocracy: How the Social Hierarchy Enables Bullies to Rule Schools, Work Places and Society at Large; On Borrowed Fame: Money, Mysteries, and Corruption in the Entertainment World, and Hidden History: An Expose of Crimes, Conspiracies, and Cover-Ups in American History. Don is a lifelong Beatles fan, and we’ve shared many in-depth conversations about Beatles music on his popular I-Heart Radio show, “The Don and Ella” show.

Bob Wilson is well-known in The Beatles World for his very popular podcast with Warren Brown, “Tomorrow Never Knows” and his intriguing solo podcast, “Don’t Pass Me By.” He has also contributed several articles to Beatles Magazine.

This month, Don and Bob Wilson are releasing their first venture into Beatles investigative research. After interviewing numerous Beatles friends and experts about the “Paul is Dead” controversy, they will soon be releasing From Strawberry Fields to Abbey Road: A Billy Shears Story. Here are their insights on “I’m Only Sleeping.”

Jude Southerland Kessler: Don and Bob, John wrote many songs about sleep in his Beatles and solo career. Sleep was a muse to him, a mystical place to seek inspiration. And sometimes, it was simply a place to escape. How do you view sleep in this particular rendition? Is John talking about shutting out the world or letting in creativity?

Don Jeffries and Bob Wilson: We know that John loved to sleep and also to lie in bed. Apparently, his bed was a kind of refuge for him. It’s no accident that the “Give Peace a Chance” video took place during John and Yoko’s “Bed-In for Peace.” John would touch upon the theme of sleep in other songs, such as “I’m So Tired.” During his solo career, he wrote both the scathing attack on Paul McCartney, “How do you Sleep?”(on which Harrison also played) and the aptly titled “Number 9 Dream.”

But John’s “bed-in” time didn’t necessarily note slothfulness. In fact, In “I’m Only Sleeping,” to quote author Hunter Davies in Beatles Lyrics, “The words are sharp and succinct, not at all the mark of a lazy lyricist. John loved his bed. When he wasn’t sleeping, he was often propped up on pillows, writing…John loved to stay in bed creating and writing.”

Lennon needed sleep to create; many of his songs touch on this. John famously described how “Nowhere Man” came to him, “the whole damn thing, as I lay down.” Similarly, the words to “Across the Universe” came to him as he lay in bed after an argument with Cynthia. Here, John lauds the creative process he always enjoyed in “half-sleep.” Sam Kemp of Far Out magazine referred to “I’m Only Sleeping” as “an ode to the importance of being idle.” But this sort of idleness is equivalent to receptiveness, not oblivion. John is listening, thinking, and creating.

Kessler: I so agree! We are alerted to John’s wakefulness from the very first line of the song when he sings: “When I wake up early in the morning…” And as the song progresses, John reminds us that he is “keeping an eye on the world going by my window.” Clearly, John is not sleeping but existing in that dozing state in which ideas flow freely.

What do you like about “I’m Only Sleeping”? What’s its charm for you?

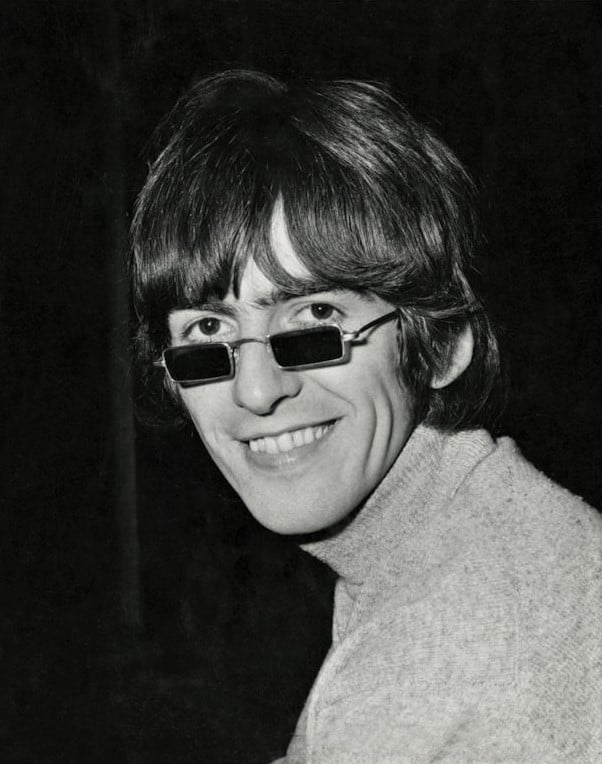

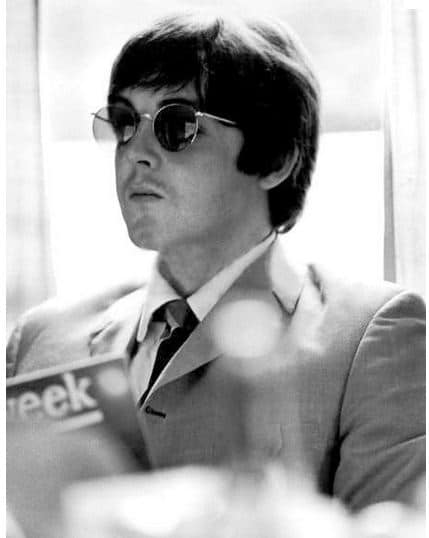

Jeffries and Wilson: I almost always love Lennon’s melodies. His voice here, as it regularly does, draws the listener in. I consider Lennon to be the greatest vocalist in the history of popular music. He could make any song contagious.

As he would do in his song “I’m so Tired,” Lennon seemed to have a special talent for melodies that make the listener think of sleep, or even feel sleepy. All anecdotal evidence suggests that Lennon’s inordinate amount of time spent in bed made him an expert on the subject.

The dreamlike sound in “I’m Only Sleeping” was enhanced by its E minor key. Furthermore, as Jude indicated in the “What’s New” segment of the blog, new studio tricks were used to create that very atmosphere. The backing track, as she explained, was recorded faster and then slowed down when played back at average speed. This evoked the image of “running through deep water” or “moving in a dream.” (And, of course, John’s lead vocal was processed in the opposite way to produce a high-pitched, far-away sound.)

Simpler techniques in the recording also catch my attention. For example, Paul actually yawns during the song. And John’s word choices cleverly evoke a “hussssshed” feeling of sleep: lazy, crazy, speed, staring, ceiling, shake me. The song’s repeated “s” and “sh” sounds lull us.

However, I’m not the only one who admires this song. Steven Spignesi and Michael Lewis, in The 100 Best Beatles Songs, rate it at #57. They call it: “One of the band’s drowsiest, most lethargic songs” but point out that it has “John’s cleanest and most well-written lyrics.” (p. 182) And in Revolution in the Head, noted author Ian McDonald says, “‘I’m Only Sleeping’ with its dreamy multitracking, a dim halo of slowed cymbal sound, and softly tiptoeing bass is…deep in artifice. The Beatles…[created] a new sonic environment.” And while admitting that the song’s theme is sleep and lethargy, MacDonald notes that “I’m Only Sleeping” was “more active than anything [John Lennon] had written since ‘Girl.’”

Kessler: Don and Bob, some music critics have claimed that this song is about drug usage, not sleep. Which theory do you support and why?

Jeffries and Wilson: I don’t think there are any drug inferences here, although certainly, the ethereal nature of the song might lend itself to being listened to while smoking marijuana. People have often claimed drug messages in Lennon’s songs. Lennon’s lyrics were sometimes ambiguous enough to be open to multiple interpretations, but in this case, it seems pretty clear that it’s a simple song about the joys of half-sleep and the creativity found there.

In his book Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, Dr. Kenneth Womack notes that a big difference is observed when John is writing about drugs and when he’s writing about sleep. When he’s writing about drugs, John is adrift, floating downstream. For example, “In ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ you turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream….truly surrender to the void.” However, in “I’m Only Sleeping,” John is floating upstream, awake and aware of what’s going on outside his window. This has nothing to do with drugs.

For more information on From Strawberry Fields to Abbey Road: A Billy Shears Story, HEAD HERE

For more information on Don Jeffries, HEAD HERE