Side One, Track Two

“Norwegian Wood”: A “Roll” Reversal

By Jude Southerland Kessler and Bruce Spizer

Throughout 2021, The Fest for Beatles Fans blog will take a deep dive into the songs that comprise 1965’s innovative, transitional Beatles LP — a record that Mark Lewisohn dubs “a major turning point in The Beatles’ career” — Rubber Soul. (The Complete Beatles Chronicles, 202) In our second of the series, Louisiana natives and Beatles authors Bruce Spizer and Jude Southerland Kessler look at what we already know about this edgy song, “Norwegian Wood,” and what we can discover in a fresh, new look! Enjoy!

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 12 October and 21 October 1965

Time Recorded: 7.00 – 11.30 p.m. on 12 October

2.00 – 7.00 p.m. on 21 October

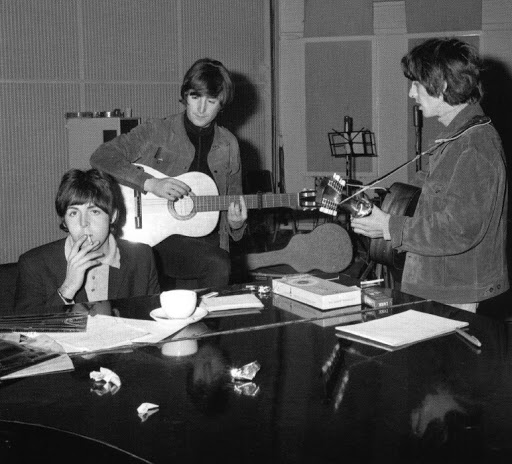

Studio: EMI Studios, Studio 2

Tech Team:

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Norman Smith

Second Engineers: Ken Scott and Phil McDonald

(Margotin and Guesdon add Ron Pender)

Original Song Title: “This Bird Has Flown”

Stats: Recorded in 4 takes on 12 October and then completely re-made in 3 takes on 21 October.

Instrumentation and Musicians:

John Lennon, the composer, plays acoustic rhythm guitar and sings lead vocal.

Paul McCartney plays bass, piano, and supplies backing vocal.

George Harrison plays lead guitar and sitar. This is the first time the sitar has been used in a pop recording, according to Mark Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 63, and Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 201.

Ringo Starr plays tambourine, maracas, and finger cymbals. (In the 12 October session, Ringo played bass drum and on 21 October, he also played bass drum at the end of Take 3. Winn, 362 and 366.)

Sources: The Beatles, The Anthology, 194, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 202-203, Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 63, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 200, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 278-281, Winn, Way Beyond Compare, 362, and 366-367, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, 63-65 and 73, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 89, Riley, Tell Me Why, 158-159, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 139-141, Miles, The Beatles’ Diary, Vol. 1, 212, Babiuk, Beatles Gear, 169-173, Badman, The Beatles: Off the Record, 147-148, Norman, Shout!, 155, and Goldman, The Lives of John Lennon, 184-185.

What’s Changed:

- Musical Maturity – Despite one’s personal feelings about Albert Goldman, he most aptly observed, “When John Lennon finished recording ‘Norwegian Wood,’ he was no longer Beatle John, the Man in the Bubble Gum Mask. He was now the brilliant, young innovator who was doing more than anybody in the music business to transform the rock’n’roll of the Fifties into the rock of the Sixties.” (The Lives of John Lennon, 185) Similarly, Mark Lewisohn calls even the first iteration of “Norwegian Wood” (from 12 October) a “brilliant recording,” and he quickly adds that the final version (from 21 October) is “quite different but equally as dazzling.” Indeed, Lewisohn sees the whole of Rubber Soul as “excellent musicianship with a new lyrical direction.” (The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 203)

By the autumn of 1965, The Beatles were no longer the innocents of “From Me to You” or “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” They were multifaceted in their mastery of the studio, technological production, and lyrical composition. In “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),” composed very early in 1965 (and performed by John for George Martin on a skiing holiday in February 1965), John had progressed eons past his ingenue status. Indeed, he had become so introspective about his work that he could record a successful initial offering on 12 October — heavily laced in sitar and boasting superb harmony as well as an honest, raw Lennon vocal — and then reject this version to start all over again on 21 October, producing a cleaner, more commercially viable work. All of The Beatles were coming into their own as musicians, but even very early in 1965, Lennon seemed to be surging forward into the experimental “studio era.”

- Employment of Double Entendre – John Lennon loved wordplay. This propensity was evidenced in his first book (proclaimed by Foyles Bookstores to be 1964’s finest work in British literature), In His Own Write. During the spring of 1965, when he was composing “Norwegian Wood,” John was completing his second volume of prose and poetry, A Spaniard in the Works. So, phrases lavishly imbued with double meaning such as “Norwegian Wood” and “I lit a fire” (although after John’s death, Paul asserted that he had coined this famous phrase) came naturally to the Author Beatle.

Furthermore, in the manipulation of the melody, John also artfully added a second level of meaning to the song. In “Drive My Car,” the powerful and independent female “running the show” speaks on one note only. Thus, she emerges as a powerful but one-dimensional character. We can’t “see” her; she exists in caricature. But the woman in “Norwegian Wood” is vividly depicted as an alluring and mysterious female — through John’s exotic melody and use of remarkable instruments. In the song’s opening waltz tempo, she beckons. In the sexy sitar sound, she seduces. She serves wine in her own boudoir and dominates her potential sexual partner. Throughout her seduction, the lilting music flows as freely as the wine, but when she resolves to sleep alone, the bridge becomes sharp, staccato, hard-hitting. John not only uses words to portray his glamorous femme fatale, but he also adds the music itself to, in clever double entendre, reveal her nature through her emanating “siren song.” Quite clever. Quite Lennon.

- Inculcation of International or “World Music” – In The Anthology, Ringo is quoted as saying that on “Rubber Soul, [we] began stretching the writing and playing…This was the departure record. A lot of other influences were coming down and going on the record…We were really opening up to a lot of different sounds.” (p. 194)

Rubber Soul is indeed replete with finger cymbals, a ching-ring (in “In My Life”), maracas, tambourines, and a “wound-up piano” (to imitate a harpsichord, in “In My Life”). (Babiuk, Beatles Gear, 169) In “Norwegian Wood,” we hear the curious and exciting sound of a sitar. Most Beatle fans know that George Harrison had been introduced to the sitar in the spring of 1965, when Director Richard Lester employed musicians to play the instrument for “comical purposes” in Help! (Norman, Shout!, 255) Badman quotes John as saying, “On the set [of Help!]…an Indian band [kept] playing in the background, and George kept staring and looking at them.” (The Beatles: Off the Record, 147-148)

Almost immediately, Harrison purchased his own sitar — “a 1940s or 1950s Kanai Lal & Brother sitar…[from] India Craft in London (Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, 63, and Babiuk, Beatles Gear, 169) and began learning to play it. Only seven months later, in October, we find both George and John willing to incorporate this unique, “funny sound” (as George Harrison refers to it in Badman, The Beatles: Off the Record, 147-148, and Babiuk, Beatles Gear, 169) into their catalogue. The Beatles’ increasing willingness to embrace international or “world music” decidedly enriched their already matchless melodies. While many of the bands of the 1960s were intent upon producing a “signature sound,” The Beatles were unafraid to push boundaries. They kept expanding horizons rather than limiting themselves to what they’d done before. The result was a thrilling, melodic lushness that never grew stale.

A Fresh New Look:

Recently, I was honored to confer with the Guru of Beatles Music History and the author of the new book, The Beatles Finally Let it Be, Bruce Spizer, about the depth and intricacies inherent in “Norwegian Wood.” Here is our conversation:

Jude Southerland Kessler: Bruce, I know that one of the new books in your successful Beatles Album Series that you are working on right now takes a look at The Beatles’ 1965 Help! LP. How did the recording techniques employed on Help! pave the way for what was to come on the revolutionary LP that was late 1965’s Rubber Soul?

Bruce Spizer: The Beatles’ first two albums were recorded on a two-track recorder, most often with vocals on one track and instruments on the other. The two tracks were then mixed down for a mono mix in which the vocals and instruments were balanced for maximum effect. These performances were live in the studio, with The Beatles playing their instruments and singing at the same time. Sometimes an instrument, such as keyboards by George Martin or harmonica by John, would be overdubbed to enhance the track. Other times, a vocal would be double-tracked. But for the most part, the recordings were vocals backed by two guitars, bass and drums.

By A Hard Day’s Night, the group was recording on a four-track recorder. This gave them the opportunity to break up the vocals and instruments onto separate tracks. For example, they could record the bass and drums on track one, the guitars on track two, the lead vocal on track three and leave four free for overdubs. They could then play back the tape and record a second vocal and another instrument, such as tambourine, on the fourth track of the tape while listening to the already recorded vocals and instruments.

For Beatles For Sale, George Martin and the group took greater advantage of the four tracks, routinely double-tracking vocals and using exotic percussion instruments.

On the “Help!” LP, the process evolved even more, and the group began experimenting with different instruments and effects. George Martin added a string quartet to “Yesterday.” The Beatles were also moving towards more of a folk-rock sound, as could be heard on some of the later tracks recorded for Help!, including “I’ve Just Seen A Face” and “It’s Only Love,” both of which would end up on the Capitol version of Rubber Soul in the U.S.

And it wasn’t just the recording of the Help! album that influenced Rubber Soul and well beyond. On the set of the movie Help!, as Jude mentioned, George became acquainted with the sitar, an Indian string instrument. There was a scene in a restaurant where musicians were playing Beatles songs on Indian instruments. This was the idea of the film’s musical director, Ken Thorne, who was used instead of George Martin, who did not get along particularly well with the film’s director, Richard Lester. Had Martin been the film’s musical director, he may not have chosen the Indian instruments and Harrison may not have been introduced to the sitar on the movie’s set. On the other hand, Martin had used sitar on a Peter Sellers’s recording, so he may very well have used Indian instruments in the film’s soundtrack. We will never know if Harrison would have picked up the sitar had Martin done the score. We do know that it was Thorne’s use of Indian instruments that exposed George to a whole new world of music.

Anyway, by the time The Beatles recorded Rubber Soul, they had mastered the recording techniques on the four-track and were branching out to different instruments, going way beyond the two guitars, bass and drums line-up. They were looking for new sounds and were using different instruments to get those sounds.

Kessler: You mentioned the sitar…let’s talk a bit more about that emerging instrument. From its debut on Rubber Soul, the sitar became a staple with The Beatles, specifically with George Harrison. But learning to control the sound of this exotic, new instrument was a journey. How did the sitar’s presence alter and develop on “Norwegian Wood” from Take 1 to Take 4? What were the technical difficulties inherent in recording the sitar?

Spizer: As Jude has pointed out, The Beatles recorded “Norwegian Wood” at two separate sessions. Take 1 was recorded on 12 October 1965, under the title “This Bird Has Flown,” during the first day of recording for the album. Although it was completed in one take, the song was given several overdubs. The finished master featured John’s lead vocal, his and Paul’s backing harmonies, acoustic guitar and bass, percussion (finger cymbals, tambourine and maracas) and George on sitar. While the sitar adds a new sound for The Beatles, George’s playing is a bit labored. He is gaining familiarity with the instrument, but still has a long way to go.

Although Take 1 was remarkable and could have been issued “as is,” The Beatles decided to completely re-record “Norwegian Wood” on 21 October. John had difficulty with his acoustic guitar part on Takes 2 and 3, but nailed it on Take 4. The basic backing track included John on lead vocal and acoustic guitar, Paul’s backing vocal and bass, and George on 12-string acoustic guitar. George overdubbed a much-improved sitar part. Knowing George Harrison’s dedication to getting his solos exact, I am sure he practiced it many times over before the re-recording of the song. Other embellishments included tambourine, a clapping sound, Ringo’s bass drum, and a crash cymbal at the end of the song.

The sitar must have posed issues for the Abbey Road engineers. The sitar does not have an electric pickup, so its sound signal is not sent directly from the instrument to an amplifier like an electric guitar or bass guitar. It must be recorded through a microphone. The trick is where to place the microphone as it needs to pick up the strings on which the melody line is played as well as the drone strings.

Based on the recording appearing on Rubber Soul, I think George and the engineers did an excellent job, particularly considering their relative unfamiliarity with the sitar.

Kessler: In Revolution in the Head, Ian MacDonald claims that “Norwegian Wood” is “the first Beatles song in which the lyric is more important than the music.” (p. 130) Do you concur? We know John was a master of wordplay, especially double entendre. How did he use that tongue-in-cheek literary technique in this song?

Spizer: I wouldn’t go as far as Ian on that one. I would say that the lyrics and the words are equally important. And while the words to “Norwegian Wood” are a long way from “Love, love me do/You know I love you,” John had already showed his fondness for the double entendre on “Please Please Me,” way back on the group’s second single. Similarly, the lyrics on “There’s A Place” from the group’s first album go way beyond the simple love songs of the day, hinting at John’s reflective nature that would find its way into later songs, such as “I’m A Loser,” which also was recorded before “Norwegian Wood.” The song was not even the first by John to tell a story. That distinction goes to “No Reply.” No doubt the words to “Norwegian Wood” are among John’s best from 1962 – 1965, but I would not consider the song to be the first where the words were more important than the music.

Also, as I’ve already said, the music on “Norwegian Wood” is equally important. It has a catchy melody line and excellent guitar playing by John and George. And it provides a new sound for the group through George’s sitar playing. As Jude pointed out, it represented the first time the sitar was featured in a released rock song. (The Yardbirds tried sitar on their 1965 recording of “Heart Full Of Soul,” but it didn’t sound quite right. Instead, Jeff Beck played his guitar part to emulate the sitar.)

John’s lyrics were in and of themselves a double entendre in the sense that there is more than one thing going on. John was trying to write about an affair, but to disguise it so that his wife Cynthia wouldn’t catch on. John had a great opening line that lent itself to telling a story: “I once had a girl, or should I say, she once had me.” Now that’s really tongue-in-cheek! From that line, the song evolved into a story of an evening in a woman’s flat where the principal décor was wood—cheap pine, often referred to then as Norwegian wood. (Thus, the tile of the song refers to the apartment’s furniture.) After being led on by the girl and then forced to sleep in the tub, the singer awakes to find himself alone. Although the ending words, “So I lit a fire, isn’t it good, Norwegian wood,” could be interpreted to mean lighting a fire in the fireplace to keep warm, Paul has said it meant that the singer burned down the house as an act of revenge.

Kessler: Bruce, can you tell us something about “Norwegian Wood” or about Rubber Soul that we haven’t considered or discussed?

Spizer: “Norwegian Wood” is the second song on both the Parlophone U.K. version of Rubber Soul and the Capitol U.S. version of the album. Interestingly, however, it follows two completely different style opening tracks.

On the U.K. album, the song follows “Drive My Car,” which is a hard rocker. It sounds totally different than “Norwegian Wood,” but the two songs work well together because of their lyrics. “Drive My Car” is not a typical pop love song. It has a story line about an interesting girl who want to be famous, but is not quite there yet. She doesn’t even have a car! And, of course, the phrase “drive my car” is one that serves as sexual double entendre. And even though, musically, the first two songs on the album are worlds apart, the “Beep beep beep beep, yeah!” ending of “Drive My Car” flows nicely into John’s lovely acoustic guitar intro to “Norwegian Wood.”

On the Capitol album, “I’ve Just Seen A Face” is the perfect musical lead into “Norwegian Wood.” Both have intricate acoustic guitar parts and have that same folk-rock sound that dominates the Capitol version of Rubber Soul. As for the lyrics, “I’ve Just Seen A Face” is a typical pop love song, whereas “Norwegian Wood” certainly is not.

The bottom line is that “Norwegian Wood” is such a great song that it works well as the next track to two completely different sounding songs!

An oddity: The song was originally titled “This Bird Has Flown.” Then, it was nearly called “This Bird Has Flown (Norwegian Wood)” before the final title became “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).”

A remarkable achievement about the Rubber Soul album in general: The recording sessions were rushed as The Beatles needed to complete 14 songs for an album plus two more for a single in time for release for the 1965 Christmas season market. Yet these sessions yielded the best crop of songs for any album. Out of the 16 tracks recorded during the session, eight (one-half) appear on the red hits collection! No other album session comes even close!

To learn more about Bruce Spizer and his remarkable Beatles Album Series, including the new book, The Beatles Finally Let it Be, CLICK HERE

And follow Bruce on Facebook HERE