Here we go, Fest Family, with our seventh “deep dive” of 2021 into The Beatles’ exceptional LP, Rubber Soul. I was thrilled to tackle this classic ballad with Jerry Hammack, respected author of The Beatles Recording Reference Manuals. As an expert on precisely what transpired in EMI Studios, Jerry has a unique perspective on this song. (You’ll be especially interested in his comments on the song’s lead line!) He gives us an opportunity to examine “Michelle” with a fresh, new look even though it’s a beloved song that we’ve cherished for 56 years.

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 3 November 1965

Time Recorded: 2:30 – 11:30 p.m.

Studio: EMI Studios, Studio 2

Tech Team

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Norman Smith

Second Engineer: Ken Scott

Jerry Boys dropped in on the recording session but didn’t work on the session. (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 67) Richard Lush and Jerry Boys did tape on the mixing sessions.

Stats: To quote Jerry Hammack, “One take was all that was required to perfect the backing track.” (Vol. 2, p. 84) Of course, superimpositions would follow.

Instrumentation and Musicians:

Paul McCartney, co-composer (Paul wrote the verses for this song from a “parody” song he had performed whilst at the Liverpool institute.) He sings lead vocals, plays bass on his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S, plays acoustic guitar on his 1964 EpiphoneFT-79N and possibly, also supplies the lead guitar solo on his 1962 Epiphone ES-230TD. (Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2: Help Through Revolver, 84)

John Lennon, co-composer (John devised the concept for this song from an old college tune he’d heard Paul perform, and he wrote the song’s middle eight.) John sings backing vocals.

George Harrison sings backing vocals. (Some sources attribute the lead line to George Harrison. Other sources attribute the rhythm line to George Harrison)

Ringo Starr plays drums on one of his Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum sets. (Hammack, 84)

Sources: Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 204-205, Lewisohn, The Recording Sessions, 67, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 292-294, Winn, Way Beyond Compare, 372, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2: Help Through Revolver, 84-85 and 250-253, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 94, Riley, Tell Me Why, 162-163, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 202, Spignesi and Lewis, The 100 Best Beatles Songs, 237-239, Miles, Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now, 273-275 , MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 140-141, and Everett, The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul, 324-328.

What’s Changed:

- Lennon/McCartney provide the second “true collaboration” on this LP — When The Beatles were searching for a few songs to fill out their Rubber Soul retinue, John recalled a piece that Paul had performed during their college days — a song that parodied the French existential artistes, such as Sacha Distel and Juliette Greco. He told Paul, “D’you remember the French thing you used to do at…parties?…Well, that’s a good tune. You should do something with that.” (Miles, Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now, 273) John encouraged Paul to “dust off” the clever, tongue-in-cheek ditty and rework it for the LP.

As Paul began to re-shape the college piece into a ballad, John composed a touching middle eight that was derivative of love letters he had written to Cynthia during their college romance. In Ray Coleman’s book, Lennon, you can see one such letter on pp. 104-105. The “I love you, I love you, I love you/that’s all I want to say” line is almost a direct quote from John’s early impassioned Christmas card to the girl he adored. He also suggested to Paul that the emphasis should fall on the word, “love.” (Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 94) Years later, in the Playboy Interviews with David Sheff, John states that the middle eight was also influenced by Nina Simone’s “I Put a Spell on You,” but clearly, John had been penning lines such as these to Cynthia in the late 1950s.

Very much like “We Can Work It Out” in which Paul wrote the verses and John composed the middle eight — adding what John called “a bluesy edge” to this song — (Everett, The Beatles as Musicians, The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul, 326) “Michelle” is a true collaborative effort.

- “Reunion” with Ivy Vaughn — All of us know that Ivan “Ivy” Vaughn brought Paul to the Woolton Garden Fête in 1957 to hear the Quarry Men perform and to meet the group’s founder and leader, John Lennon. Ivy’s role in The Beatles’ legend looms large! But he or rather his wife Jan, a French teacher, also figured into the creation of “Michelle.” Not being fluent in French and wanting to keep the song’s female character a mysterious French femme fatale, Paul rang the Vaughns, seeking Jan’s help. He wanted a pet phrase that rhymed with “Michelle” (to which Jan supplied “ma belle”) and approving of that, he asked her, “What’s French for ‘These are words that go together well?” Of course, we all know Jan’s response was: “Sont des mots qui vont tres bien ensemble.” And voila! Once again, the Vaughn family had claimed a significant role in Beatles’ history. (Miles, Many Years From Now, 273-275)

- A brilliant study in contrasts — Probably unintentionally, in “Michelle,” The Beatles gave us a study in contrasts: English boy/French girl, electric instruments/acoustic instruments, major chords/minor chords. And interestingly, Stephen Spignesi points out that although this is a highly emotional song, “Paul’s vocal is restrained and (dare I say it) somewhat unemotional.” (The 100 Best Beatles Songs, 239) This balance of opposites makes the ballad unique. As Spignesi observes, “Throughout the song, there is a sense of discretion. In a word, ‘Michelle’ is subtle. As it should be.” (p. 239)

A Fresh New Look:

Recently, Fest Blogger Jude Southerland Kessler, author of The John Lennon Series, visited with author, Jerry Hammack about some of the finer points of Lennon/McCartney’s “Michelle.” Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference, Vol. 2: Help Through Revolver (1965-1966) — researched meticulously for over a decade — provides even more detailed information about this fan favorite. As an experienced Canadian-American musician, producer, and recording and mix engineer, Jerry Hammack has insights into this song that many of us would miss. Be sure to attend his presentations at The Fest, where he always a sought-after guest speaker!

- Jerry, one of the most interesting aspects of your analysis of this song in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2: Help! through Revolver (1965-1966) is your strong thesis that Paul (not George Harrison) performed the exquisite lead solo in “Michelle.” Please tell us about the evidence you’ve amassed that supports this theory.

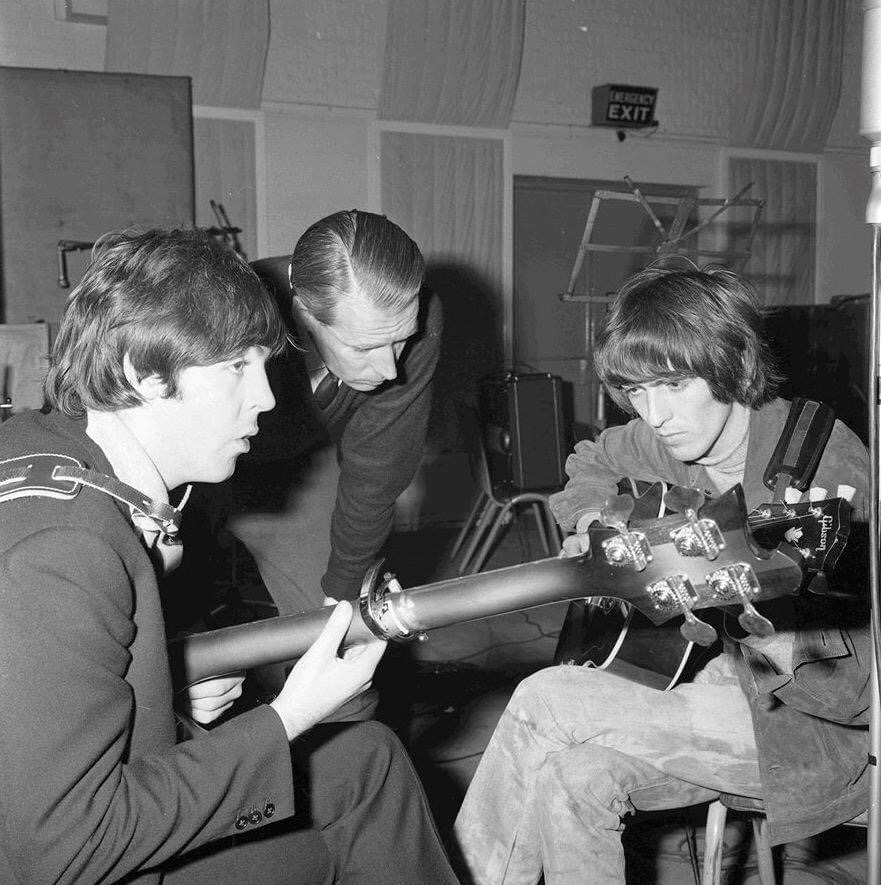

There are multiple aspects of the solo part supporting the conclusion that Paul was responsible for this work on the song. The playing style of the part bears no resemblance to any of Harrison’s playing during this period, while it has great similarity to Paul’s bass work. The solo is played entirely in the mid-range of the guitar, much like a jazz-style bass solo would be played. Photographic evidence from sessions during this period show Paul’s Epiphone guitar leaning against the Bassman amplifier, and the muted sound of the part would be consistent with the frequency characteristics of that amplifier as set up for bass playing, as well as the AKG D20 commonly used to mic that cabinet.

But the primary evidence is the tape log, which accounts for an original tape and a tape reduction remix on a second reel.

The performances for the song’s arrangement are few – two acoustic guitars, bass, lead guitar, lead vocal and backing vocals. After the backing track of acoustic guitar, lead vocal and drums was completed, Paul superimposed bass and lead guitar onto the song, each onto their own track. The tape-to-tape reduction then made room for his final acoustic guitar (doubling parts of the original performance) and backing vocals by John, Paul and George.

If George had played the solo, there would have been no need for a tape reduction remix. The four-track could have supported all the performances that make up the track without it. The only reason to put the bass and solo on separate tracks is because one person can’t play both at the same time. That person is Paul.

- Jerry, in the “What’s New” section, I talked briefly about the use of contrasts in this song. And one of those contrasts is the juxtaposition of major and minor chords. For those of us who aren’t music experts, please tell us a bit about the clever way in which those major and minor chords are artfully employed in “Michelle.”

Not that I’m a music expert myself…As Walter Everett notes, the song is mixed modally between F-major and F-minor, which is pretty sophisticated for a pop song. Paul even manages to throw in a few diminished, major and minor 7ths and 9ths. McCartney is believed to have drawn on influences as far ranging as French artists Sacha Distel and Juliette Greco for his inspiration, and perhaps, more practically, from lessons he learned in songs like “Bésame Mucho” that also play with major/minor inversions.

- You point out in your Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2 that “Michelle was the first track to feature bass as a superimposition.” Why is it so important that the bass be given its own track in this song and in many Beatles songs to follow (especially the tracks on Sgt. Pepper)?

The reason the bass was given its own track in “Michelle” was a practical one as I’ve noted earlier, but the benefit of recording it on its own is in control over the tone and volume level of the instrument when it came to creating a mix — in this case, a reduction mix. If it had been recorded with another instrument like a guitar, the volume relationships would already be fixed, and tonal decisions when it came to mixing would have to be balanced out. (A reduction mix is similar to a final mix.) Too much bass on a guitar signal and the guitar sounds muddy and thick – too much treble on a bass signal and it sounds thin.

The lessons learned with the control gained on the bass signal through the recording of “Michelle” didn’t necessarily alter the approach to bass recording overall, but the approach was called upon again in the Pepper era and whenever the sound that Paul wanted from the bass was more up-front and unique.

- As we discussed in the “What We Know” section, “Michelle” was rather hastily assembled in the autumn of 1965, and it was, originally, a wry spoof of French beatnik singers from Paul’s Liverpool Institute days. And yet, this song emerges as anything but a lighthearted caricature. In fact, “Michelle” won the Grammy Award for “Song of the Year” in 1966. What makes this composition so brilliant?

For myself, what makes the song so brilliant is that quality of complexity disguised as simplicity. The Beatles make the song sound almost effortless, natural, like it always existed, and they just happen to be playing it for us. As with the best actors, the effort is hidden; the impression is that of ease. There’s nothing about “Michelle” that isn’t sophisticated (and some cover versions fail by how painfully obvious they display the fact), but The Beatles flow through the track like a river that knows where it’s going. It’s just so naturally performed. Hiding behind that perception of ease is a beautifully complex song, adding a whole other level to the experience. The more you know about what The Beatles pulled off with “Michelle”, the more you enjoy it.

For more information on Jerry Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference Manuals, head here