Side Two, Track Five

“I Want to Tell You” said George…and Anthony!

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Anthony Robustelli

This month, the Fest for Beatles Fans Blog takes an in-depth look at Revolver’s “I Want to Tell You.” Jude Southerland Kessler, our Fest Blogger and author of The John Lennon Series works hand-in-hand with Anthony Robustelli, author of (wait for it…) I Want to Tell You, The Definitive Guide to the Music of The Beatles, Vol. 1, 1962-1963. Who better to give us a “Fresh, New Perspective” on George’s third song on this pivotal LP than Anthony? He wrote the book!

Anthony holds a degree in music from NYU, and since 1996, he has run his own successful recording studio, Shady Bear Productions. Also, as a sought-after stage musician, Anthony has performed with Gloria Gaynor, Bo Diddley, Michael Franti & Spearhead, and many more. In 2022, he opened for Sir Paul McCartney at the Glastonbury Festival. Wow! We are very honored to have Anthony – a frequent Guest Author at the Fest for Beatles Fans – take time out from his crazy-busy schedule to share with us!

And… we can’t wait to see each and every one of you at the Hyatt Regency O’Hare for the Chicago Fest for Beatles Fans, August 9-11! The lineup is too good to miss! Get your tickets and get ready for the time of your life!

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 2 June 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time Recorded: Early in the session, which ran from 7.00 p.m. to 3.30 a.m.

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 74)

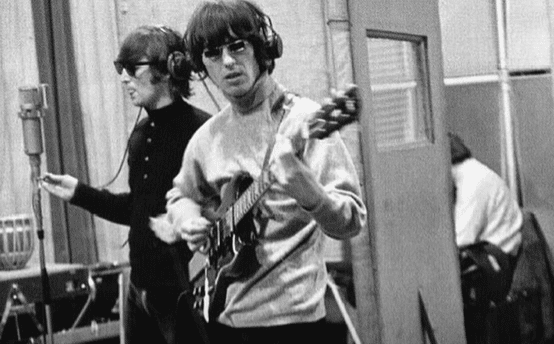

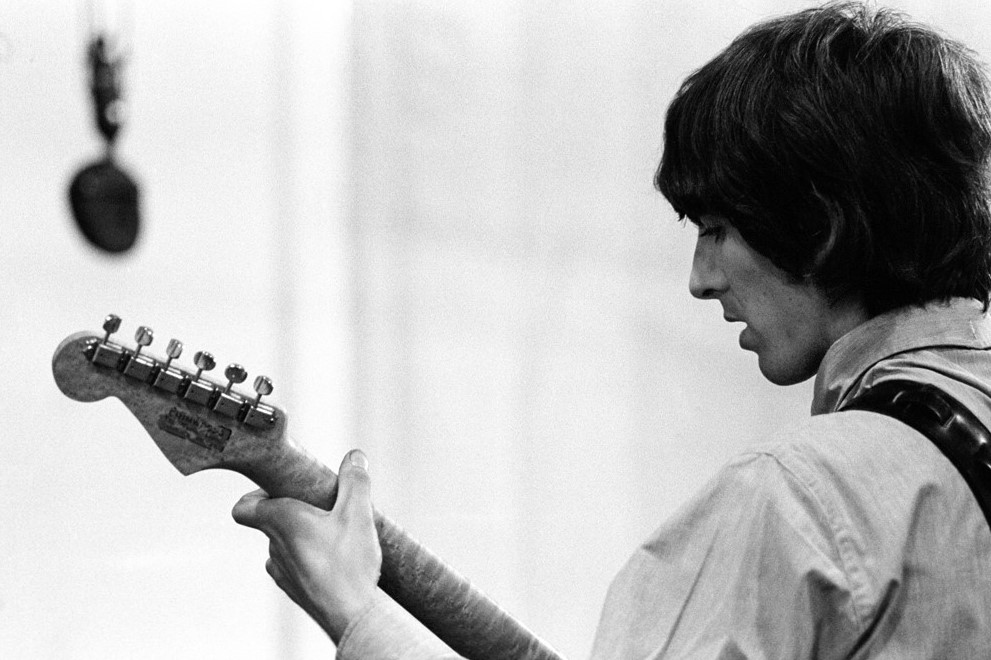

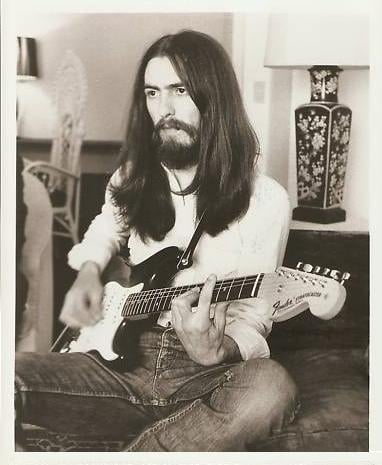

On this day: The Beatles did five takes to capture the backing track. Take 3 was selected as “best.” The track featured George Harrison (the composer and lead singer) on one of three guitars that he had in studio: either his 1961 Fender Stratocaster, his 1964 Gibson SG Standard, or his 1965 Epiphone ES-230-TD, Casino. Paul McCartney played the studio’s Steinway “Music Room” Model “B” Grand Piano, and Ringo Starr was on his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set. John Lennon sang backing vocals with Paul McCartney; these were added in superimposition, as was a piano part by McCartney. One of The Beatles (some sources designate John; others say Ringo) added a superimposed maracas part. After a tape reduction remix, dubbed Take 4 (regardless of the fact that a Take 4 already existed), handclaps were added onto the new Take 4.*

Second Date Recorded: 3 June 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time Recorded: Early in the session which ran from 7.00 p.m. to 2.00 a.m.

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 82)

On this day: Paul McCartney’s bass line (played on his Rickenbacker 4001S) was superimposed onto the new Take 4. This completed The Beatles’ work on the song.*

*From Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 144-146.

Sources:

Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 81-82, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 224, The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology, 209, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 66 and 68, Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, Womack, Long and Winding Roads, 145, Harry, The Ultimate Beatles Encyclopedia, 334, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 23, Gould, Can’t Buy Me Love, 362-363, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 215-216, Turner, Beatles ’66, 157-159, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 115, Turner, Beatles ’66, 260 and 261, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 346-347, Riley, Tell Me Why, 196-197, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 166, O’Toole, Songs We Were Singing, 111-112, 231, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 144-146, Spizer, The Beatles From Rubber Soul to Revolver, 221, Miles, The Beatles Diary, Vol. 1, 232 and 239, Everett, The Beatles as Musicians, Revolver Through Anthology, 57-58, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 174-175, Hertsgaard, A Day In the Life: The Music and Artistry of The Beatles, 187-188, and Mellers, Twilight of the Gods, 79-80.

What’s Changed:

- Separate Bass Overdub – On 3 June, 1966, Paul’s bass overdub on the Rickenbaker 4001S was done separately from the other instruments. Paul had overdubbed his bass previously. For example, on 10 November 1965 he added the bass as a superimposition for “The Word,” but the bass was not added individually. In The Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn states, “It was, for the first time on a Beatles recording, a bass guitar superimposition only.” (p. 82) Lewisohn points out that this “afford[ed] it a vacant track on the four-track tape, [which] allowed a greater dexterity with the sound in the re-mix.” In The Beatles From Rubber Soul to Revolver, Spizer goes on to say that this practice also “enabled [Paul] to come up with [a] more melodic bass line…” (p. 203) Lewisohn notes that this technique is something “that would become more commonplace during and after 1967.” (Beatles Recording Sessions, p. 82)

- Time Constraints – The 2 June recording of the rhythm track for “I Want to Tell You” was completed efficiently. In fact, Lewisohn refers to it as: “A quick recording.” (The Beatles Recording Sessions, 81)

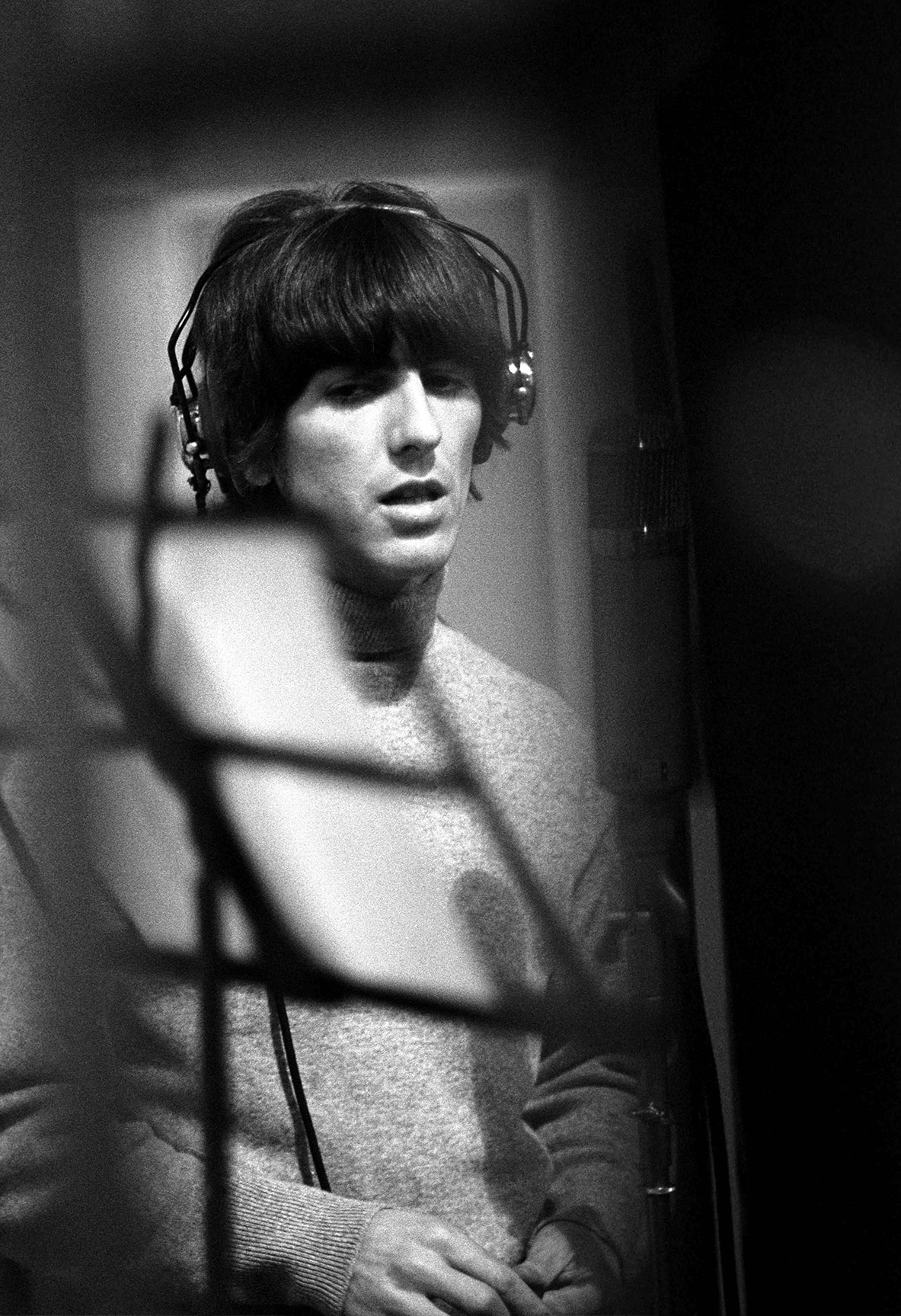

Then, Lewisohn quotes Geoff Emerick as saying: “One really got the impression that George was being given a certain amount of time to do his tracks whereas the others could spend as long as they wanted. One felt under more pressure when doing one of George’s songs.” Although Geroge was given three songs on Revolver rather than his customary one (or two, at best), the amount of time allotted for recording and re-recording was not as lavishly spent on Harrison’s number as it was on Lennon and McCartney’s. George was, as Emerick himself observes, expected to “Turn to!” (Meaning, get to work.) Perhaps (nudge, nudge, wink, wink) that is one motivation behind the 129 times that George recorded and re-recorded “Not Guilty” for the Esher Demos.

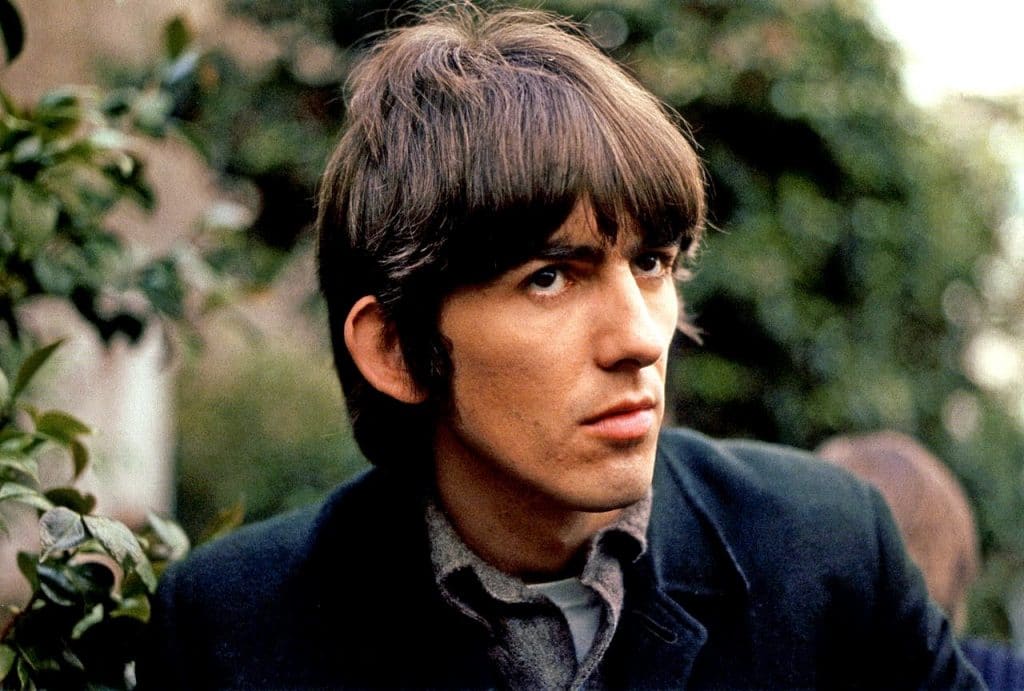

Although George was not always treated equitably, Robert Rodriguez in Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, points out that, “Though it would be a long time before his senior Beatle partners would come to regard [George] as anything approaching an equal, proximity to the two masters accelerated the learning curve.” (p. 66) As proof of that extraordinary growth, Rodriguez points to the “thematic complexity” of “I Want to Tell You” (which we will discuss below) and says it is “found nowhere else on the album. It marked George’s ascent to a world-class songwriter.” (p. 66)

- Three Prelim Titles – By now, everyone realized that George Harrison struggled with song titles. In The Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn shares this fun bit of verbiage in Studio Two from 2 June, 1966:

Martin: What are you going to call it, George?

Harrison: [who doesn’t know] I don’t know!

John: Granny Smith Part Friggin’ Two! (To George) You never had a title for any of your songs!

To which, Geoff Emerick suggests another British apple, “Laxton’s Superb.” (p. 81)

By 3 June, Harrison’s song title had morphed from “Laxton’s Superb” to “I Don’t Know.” Then, at the end of the evening, it became “I Want to Tell You.” Three titles for a Harrison number. A new record had been set!

More on the apple-themed titles from Anthony Robustelli in the “Fresh, New Look” segment.

- Much-Debated Lyrics – When asked about the message of this song, George said, “‘I Want to Tell You’ is about the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or transmit.” And Beatles experts echo the composer’s intent, but add that other topics are in play as well. For example, Riley in Tell Me Why says, “This song shuns the modern anxieties with time and seeks exchange and the enlightened possibilities that lie outside fixed Western boundaries.” (p. 196) Womack in The Beatles Encyclopedia, Vol. 1 adds, “Clearly written with Eastern notions of karma in mind, ‘I Want to Tell You’ addresses the individual as the result of a set of totalizing, lived experiences.” (p. 434) And although Mellers repeats that Harrison’s theme is “the difficulty of communication,” he asserts that “I Want to Tell You” has “no Eastern connections.” (Twilight of the Gods, p. 79) Finally, Miles tells us that the song is about George’s “determinedly realistic view of relationships, in which failed communication was the order of the day.” (The Beatles Diary, Vol. 1, 239) Miles goes on to say that “all of [George’s] portrayals of love were surrounded in misunderstanding and the dreadful prospect of boredom, and this was no exception.” (The Beatles Diary, Vol. 1, 239)

Early Beatles songs from 1963 and 1964 focused on touching but simpler themes such as “I love you,” “She loves you,” “You love me,” and (in the case of “You’re Gonna Lose That Girl”) “You don’t love her enough.” Now, however, both fans and critics find themselves examining songs with complicated meanings and myriad interpretations. The exciting tracks on Revolver – and this Harrison composition in particular – offer layers of complex messages that would be debated for the next 60 years…thus far.

A Fresh, New Look:

We welcome our friend Anthony Robustelli to the Fest Blog for July! Besides being a frequent presenter at the Fest for Beatles Fans, I’ve also shared happy times with Anthony at Beatles at the Ridge and the GRAMMY Museum of Mississippi “Beatles Symposium.” With Anthony’s vast knowledge of music and recording techniques, I’m looking forward to his “Fresh, New Look” at George Harrison’s “I Want to Tell You.”

Jude Southerland Kessler: Anthony, thanks so much for taking time out from your studio, your own music, and your research for what I HOPE will soon be the new volume of your amazing book on ALL Beatles songs (both originals and covers), I Want to Tell You. Your work is so thorough that I know your answers here will give us all some new insights into this familiar 1966 song. So, with that in mind… George Harrison’s “I Want to Tell You” does not, at first glance, seem to exhibit as profound an Indian influence as does say “Love You To” or Sgt. Pepper’s “Within You, Without You.” But there are subtle touches both musically and lyrically that incorporate George Harrison’s passion/beliefs. Tell us about those, please.

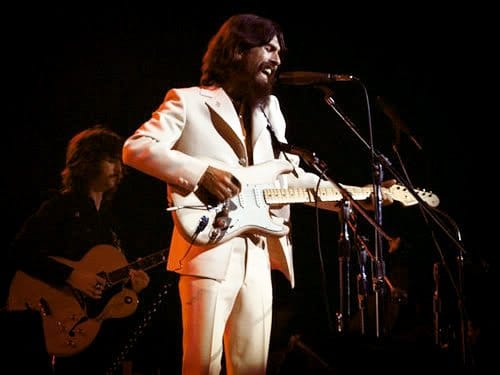

Robustelli: While “I Want to Tell You,” doesn’t necessarily use Indian instruments, it conveys an Eastern feeling that is apparent in “Love You To” and later, on a grander scale, “Within You Without You.” Harrison’s vocal performance is full of bends reminiscent of the dilruba, a bowed Indian instrument later heard on “Within You, Without You.” He also makes good use of an odd number of measures (eleven to be precise) for the verse which keeps the listener off balance. Many believe that there’s a bar of 2/4 snuck in there at bar four, but Harrison just changes chords in the middle of the bar while “just confusing things.” Interestingly, McCartney also adds some of these elements to the song, as he did with his blistering Indian influenced guitar solo on “Taxman.” The piano phrase in bars six through nine highlight the flattened ninth of the E chord – quite a jarring development – and the melismas he sings on the outro are Eastern flavored. Even the fade out has a drone-like quality with McCartney’s bubbling bass that pedals underneath Harrison’s striking guitar riff.

Kessler: It’s interesting that in a song about how difficult it is to express one’s feelings, George looked back at the lyrics years later and said that he got the words wrong and would change them if he could. What did he want to change and why?

Robustelli: With his newfound interest in Eastern religion Harrison found himself at odds with the Western philosophy that often put financial success above spirituality. He was still having problems expressing himself with his lyrics, and the inability to communicate is the main focus of the song. He even had trouble naming his songs with “Love You To” having a working title of “Granny Smith,” named by engineer Geoff Emerick after his favorite apple. When it came time to record “I Want To Tell You” Harrison once again had no title, so Emerick decided to name it “Laxton’s Superb,” another type of apple. Harrison later stated that his new Eastern beliefs should have led him to change the lyrics to the first bridge in order to explain that rather than listen to a mind “that hops about telling us to do this or that – what we need to do is lose the mind.” When he toured Japan in 1991, he took his own advice and changed the line to “It isn’t me, it’s just my mind.” Even with the original lyric, Harrison was beginning to find his footing as a lyricist by using themes that were universal.

Kessler: Ted Nugent’s 1979 remake of “I Want to Tell You” is praised by Margotin and Guesdon in All the Songs as “a superb remake which tends to show that with more arrangements and more work what George’s song could have been.” Do you agree or disagree? Why?

Robustelli: Well, I’ve never been a fan of Ted Nugent, nor of his music, and I don’t think his cover added anything to the original. I don’t particularly like the lead guitar riffs or the fact that he adds a bar of 2/4 before the original dissonant piano phrase that begins on the E chord. While the original piano part is unexpected and swings in an inimitable way, in Nugent’s version this section is plodding and choppy. When we arrive at the middle section more horrors are in store as Nugent decides to only play a B minor chord, whereas Harrison’s original incorporates not only the B minor chord but a B diminished and a B7. These changes give the song its unstable nature and lead the ear to unexpected places, something Nugent’s version does not do. Follow this with a pedestrian guitar solo, and there really isn’t much to say of this tame, and lame, cover version of a fantastic Harrison song.

Kessler: Many music critics have said that this song was addressed to Pattie Boyd, but Riley quotes David Laing as noting that the song was meant, possibly, as a message between the artist and the audience. What say you?

Robustelli: While it could be looked at as a simple statement about his trouble expressing himself to his wife Pattie Boyd when they first met during the filming of A Hard Day’s Night two years earlier, it probably had a broader meaning. As you mentioned earlier, George stated in his 1980 book I Me Mine that “‘I Want To Tell You” is about the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit.” But his original lyrics seem to stem from the more typical trope of being unable to express feelings to a love interest. The original lyrics, “Maybe love will be the one thing to get me by,” were replaced with “I don’t mind, I could wait forever, I’ve got time” and “If you should see me and need my love to pass the time” was changed to “So I could speak my mind and tell you maybe you’d understand.” The new lyrics are more sophisticated and lend an ambiguous air to a song that is musically dissonant and unsettled.

For more information on Anthony Robustelli’s work, HEAD HERE

Follow Anthony on Social Media: