Revolver

Side One, Track Two

“Eleanor Rigby” Lives On

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Simon Weitzman

Through 2023, the Fest for Beatles Fans blog will be delving into the fine details of The Beatles’ astounding 1966 LP, Revolver. This month network TV director, producer, and author, Simon Weitzman – best known in The Beatles’ World for his beloved film A Love Letter to The Beatles: Here, There, and Everywhere – joins John Lennon Series author Jude Southerland Kessler for a fresh, new look at a track that literally changed all we had come to know about The Beatles! Simon is co-author, with Paul Skellett, of four remarkable Beatles books: Eight Arms to Hold You, All You Need is Love, The Mad Day Out with Tom Murray, and The Beatles in 3D. We’re thrilled to have Simon with us this month and in person, in just a few days, at the New York Metro Fest for Beatles Fans!

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded:

The Home Demo was recorded by Paul in late March 1966 at Ringo’s flat in Montague Square (Winn, 7)

First EMI session, 28 April 1966, Studio Two

5 p.m.- 7:50 p.m. (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 77)

Second EMI session, 29 April 1966, Studio Three

5 p.m. – 1 a.m. (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 77)

Third EMI session, 6 June 1966 in Studio Three (control room only)

7 p.m. – 12 a.m. (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 82)

Tech Team

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald

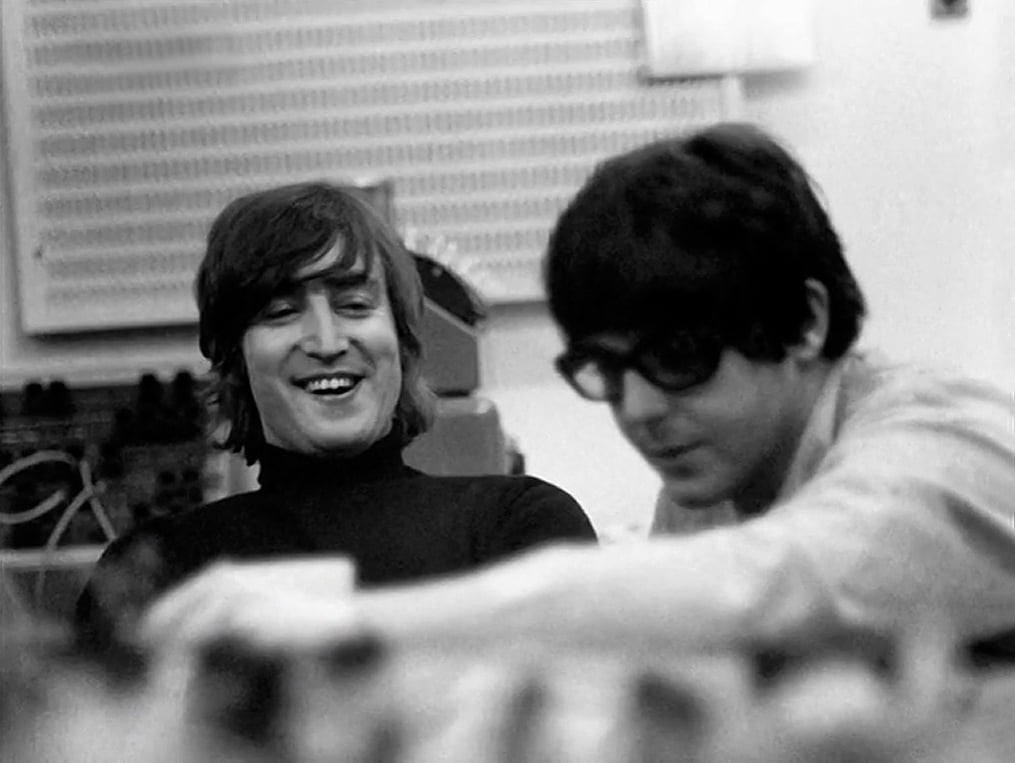

Stats: On 28 April, a professional string octet (members listed below) recorded 14 takes. On 29 April, as John C. Winn tells us in That Magic Feeling, “Paul added his lead vocal on track 4, and then he, John, and George harmonized for the choruses on track 3.” (p. 24) That evening, the tape recorder was slowed a bit to achieve a higher pitch when played at regular speed. Finally, on 6 June (spilling over into the small hours of 7 June), Paul re-recorded his vocal, employing a unique concept provided by Martin. Martin had suggested Paul “sing the chorus in counterpoint to his final vocal refrain.” (Winn, That Magic Feeling, 24)

Instrumentation and Musicians:

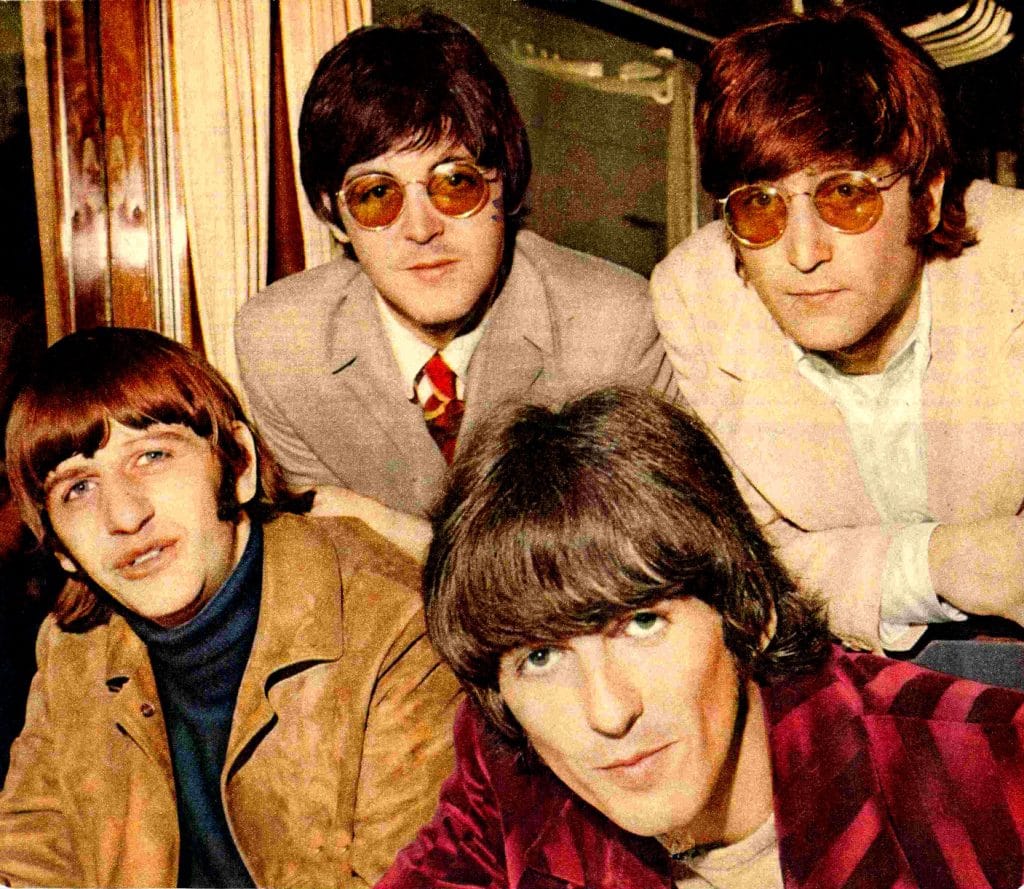

Paul McCartney, the composer, sings lead vocal.

John Lennon sings backing vocals.

George Harrison sings backing vocals.

String Octet including violinists Tony Gilbert (first violin) Sidney Sax, John Sharpe, and Jurgen Hess; violists

Stephen Shingles and John Underwood, and cellists Derek Simpson and Norman Jones. Musical arrangement by George Martin. (Hammack, 136)

Sources: Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 219, Lewisohn, The Recording Sessions, 77, Martin, All You Need is Ears, 199, Emerick, Here, There, and Everywhere, 127, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 167-169, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 144-149, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 326-327, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 7 and 24, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 136-137, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 104-105, Riley, Tell Me Why, 184-185, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 213, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 93-95, McCartney, Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, 157-163, Sheff, The Playboy Interviews, 118-119 and 151, Shotton, John Lennon: In My Life, 123-124, and MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 162-163.

What’s Changed:

Absolutely Everything!!! If you knew nothing at all about The Beatles, and heard “Love Me Do” followed by “Eleanor Rigby,” you would vow that those two songs were not composed by the same band! Even if we juxtaposed 1965’s “Help!” against 1966’s “Eleanor Rigby,” the differences would still be myriad and vast. The second track on Revolver truly changed so much that we know about The Beatles. It was a dramatic 180-degree pivot. Here are just a few of the meteoric changes:

- Instrumental Personnel – Paul sings the lead vocal while John and George sing back-up, but nary a Beatle plays an instrument on this track. The instruments are manned by a professional string octet, but not by John, Paul, George, and Ringo. That is certainly “something new”!

- Instruments – four violins, two violas, two cellos. And that is all. To quote Clang: “Shocking!”

- “A Complete Change of Style” – This quote regarding “Eleanor Rigby” (and “Tomorrow Never Knows”) is from Sir George Martin. And of course, he said it perfectly. Both songs propelled us headlong into “the new direction.” Prior to Rubber Soul and Revolver, Beatles music had been upbeat if not always optimistic. Even songs expressing crushing depression (such as “I’ll Cry Instead” and “Help!”) sound hopeful, if not downright joyous.

But “Eleanor Rigby” is unabashedly a song about painful isolation from which there is no glimmer of rescue. In The Beatles’ catalog, this is a revolutionary theme and sound. As Tim Riley observes in Tell My Why: “The ‘ah’s’ aren’t soothing, they’re aching, and the sudden drop in the cellos after the first line sinks the heart along with it.” Yes, “Misery” was a song of heartbreak but left open the possibility that the wayward girl would “come back to me.” And in “Girl,” the bickering couple only suffer through their troubles because they’re still very much in love.

But the world of “Eleanor Rigby” is a place in which “no one was saved.” In Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, Robert Rodriguez points out that even “Yesterday” holds more hope than “Eleanor Rigby.” He observes: “’Yesterday’ bore obvious commerciality with its time-honored theme of love gone wrong. But ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was a somewhat unsettling composition devoid of traditional romanticism, calculated to stir rather than to soothe.”

- Contested Authorship of Lyrics – The lyrics of only one other Beatles song – “In My Life” – has been claimed by both John and Paul. Through the years, Paul has always claimed full authorship for “Eleanor Rigby.” In Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, he goes into great detail about several “old ladies” he encountered in his youthful Bob-A-Job-Week chores – ladies who inspired the character. And Paul adds that Eleanor Bron might have reinforced the concept of using “Eleanor” as the character’s name. Then he states, “Initially, the priest was ‘Father McCartney’ because it had the right number of syllables. I took the song out to John at that point, and I remember playing it to him, and he said, ‘That’s great, Father McCartney.’ He loved it. But I wasn’t really comfortable with it because it’s my dad – my Father McCartney – so I literally got out the phone book and went on from ‘McCartney’ to ‘McKenzie.’” (pp. 157-163)

However, in the 1980 Playboy Interviews, John Lennon told David Sheff, “Yeah, ‘Rigby.’ The first verse was [Paul’s], and the rest are basically mine…we were sitting around with Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall, and he said to us, ‘Hey, you guys, finish up the lyrics.’…and I was insulted that Paul had just thrown it out of the air. He actually meant he wanted me to do it, and of course, there isn’t a word of theirs in it because I finally went off to a room with Paul and we finished the song.” John then goes into great detail about the writing process of “Rigby,” even stating that “when [he] stepped away to go to the toilet,” George and Paul were working on “Rigby” in his absence, and they came up with the line, “Ah look at all the lonely people.” When he returned, John says, “They were settling on that.” He says that he heard it, loved it, and remarked, “That’s it!” (pp. 118-119)

Later in the same interview, John restated his contribution to “Eleanor Rigby,” calling it “Paul’s baby, but I helped with the education of the child.” (p. 151)

However, in his book, John Lennon In My Life, Pete Shotton revealed a very different account of the song’s creation. Pete says that he and about 8-10 other people (including Ringo) were spending an evening in John’s home Kenwood when Paul arrived. McCartney presented those gathered with a set of lyrics for “Eleanor Rigby,” and said, “I’ve got this little tune here. It keeps popping into me head, but I haven’t got very far with it.”

Pete says, “We all sat around, making suggestions, throwing out the odd line or phrase…[When] Paul got to the verse about the cleric, whose name he had down as ‘Father McCartney,’ Ringo came up with the line about ‘darning his socks in the night,’ which everybody liked.” However, Pete says that he objected to the cleric’s name and pointed out to Paul that fans might think it is Jim McCartney having to darn socks, lonely and all alone. And when Paul agreed, Pete goes on: “…I noticed a telephone directory lying around and said, ‘Give us that phone book, then, and I’ll have a look through the Macs.” And he did. After finding and rejecting the humorous name “McVicar,” Pete says that he asked Paul to “try Father McKenzie out for size, and everyone appeared to like the lilt of it.” (Shotton, 123)

Then, according to Pete, Paul told the gathered group: “The real trouble is I’ve no idea how to finish this song.” Ideas and suggestions were thrown out at random. And Pete claims that he suggested having Eleanor die and having Father McKenzie perform the burial. Pete states that he said, “That way you’ll have the two lonely people coming together in the end – but too late.” (Shotton, 124) It was a concept, Pete tells us, that Paul seemed to endorse, but an ending that John did not care for one bit.

Quite a different tale! So, where does the truth lie? Who wrote what and when and why?

The only thread that is consistent in all accounts is that Paul took the song to John and somehow the two of them – alone or with other people – finished the lyrics as a joint effort. All other details vary, depending upon the teller of the tale. Rarely does this scenario occur with a Beatles song. Credits are shared; nods are given. But the history of “Eleanor Rigby” is much like the record’s namesake, aloof and unknown.

- Recording Techniques – When Paul McCartney told new EMI engineer Geoff Emerick that he wanted the strings on “Eleanor Rigby” “to sound really biting,” Emerick was a little intimidated. How could he achieve that? In his book Here, There, and Everywhere, Emerick tells us that he devised an outrageous plan to close-mic the strings. He explains: “String quartets were traditionally recorded with just one or two microphones placed high, several feet up in the air so the sound of bows scraping couldn’t be heard.”

Defying this unwritten rule, Geoff close-miked the instruments. It was a bold act of genius. And the result was precisely what Paul wanted! Not only did the strings supply melody but they also supplied percussion. And their “harsh realism” brought the strident authenticity of a callous world into this lonely and tragic song. (More on this in Simon Weitzman’s “Fresh, New Look” interview below.)

One final note…According to The Beatles, “Eleanor Rigby died in the church and was buried along with her name.” But in 2023, almost 60 years from her appearance in the world of The Beatles, Eleanor lives on. By the mid 2000’s, the song had been covered by over 200 musicians. Ray Charles, for example, hit No. 35 on the Billboard charts with his version of the song. In 1969, Aretha Franklin’s take on the number shot to No. 17 on the Billboard Hot 100. But these two icons are not alone in their respect for the song. Hundreds of other groups recorded their own tributes to Father McKenzie, all the lonely people, and yes, to Eleanor. In 2023, Eleanor is still with us…living on.

A Fresh, New Look:

We’re thrilled to have Simon Weitzman with us this month for a close and personal examination of “Eleanor Rigby.” Apart from his other many credits, listed earlier in the blog, Simon is working on a documentary about Beatles PA and Rolling Stones Tour Manager, Chris O’Dell. He’s also completing his wonderful film, A Love Letter to The Beatles: Here, There, and Everywhere, which you will be able to enjoy at the New York Metro Fest for Beatles Fans. Taking time out of his hectically busy schedule to discuss “Eleanor Rigby” was a real treat for the Fest staff. Thank you, Simon!!!!

Jude Southerland Kessler: Hi Simon, thank you “ooover and oover and oover again” (whoops, wrong band!!) for giving us the gift of your time. We know you’re incredibly busy, so I’ll dive right in. Simon, the 1966 addition of young Geoff Emerick to the production team at EMI certainly made Revolver an edgier, more experimental LP. Please tell us a bit about Emerick’s clever method of making the orchestral segment “hard-biting,” as Paul had requested him to do.

Its production is as exquisite as it is different. Paul was a forward-thinker and was amenable to George Martin’s suggestions that classical music be employed. Despite initial misgivings, Paul wisely followed Martin’s lead and brought classical influences firmly into the 20th century. It was familiar ground for George Martin; it enabled him to take a leap of faith with Paul and really push the strings in the recordings, whilst taking inspiration from Bernard Herrmann, who himself innovated the modern film compositions that were to shape cinema throughout the century. Indeed, “Eleanor Rigby” has a soundscape that would very comfortably sit in a number of movie soundtracks today.

“I was very much inspired by Bernard Herrmann…[he] really impressed me, especially the strident string writing. When Paul told me he wanted the strings in ‘Eleanor Rigby’ to be doing a rhythm, Herrmann…was a particular influence.”

- George Martin as quoted in The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn, 77

The sound revolution in “Eleanor Rigby” was further extended by the youthful influence of sound engineer Geoff Emerick. Emerick loved classical music but wasn’t bound by the rules and containment of his predecessors. He was more in tune with Paul’s desire to take what was known from the genre and move it into the contemporary music of the time…in effect, making classical acceptable to the pop genre and vice versa. To achieve this – as Jude noted – Emerick brought the microphones closer to the players, managing to isolate each string in a way that hadn’t been done before, This caused some of the more purist musicians some discomfort during the recordings. You just didn’t do that to musicians in session; well, not until now. As Emerick clearly stated in his book Here, There, and Everywhere: “On ‘Eleanor Rigby’ we miked very, very close to the strings, almost touching them. No one had really done that before; the musicians were in horror.”

The combination of Emerick’s soundscape enthusiasm mixed with Martin’s more orthodox approach worked perfectly to create something that sounded filmic, classical, and modern, all at the same time – just as Paul had always seen it in his mind’s eye.

Kessler: Simon, please give us your thoughts on the imagery of the desolate woman and the desperate priest whom no one could hear and whom no one drew near. What do they say to you? Is there hope in this song?

For me, “Eleanor Rigby” is about the mask we put on when we are in social situations and the personas we invent to create our own self-worth. The line: “Wearing the face that she keeps in a jar by the door” is a face we all wear when we leave our homes and try to interact and connect with the world. “Picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been, lives in a dream” for me, translates as the daydream in which most of us live as we look at what we perceive to be what we should be doing with our lives…and what we perceive everyone else is doing with theirs, as well as being the outsider who is always trying to conform.

“Father McKenzie, writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear, no one comes near. Look at him working, darning his socks in the night when there’s nobody there, what does he care?’” Again, for me the song concentrates on the lifelong search for our self-worth and ultimately, the things we do to satisfy our own perception of achievement. We are conditioned to do things that are recognized. We are educated to believe that the things we do to create our own self-worth don’t count if no one else is watching or listening. Perhaps Paul was also thinking about the apparent futility of everything. Perhaps he, too, was asking, “Does any of it matter?” and “Why are we conditioned to think like this?”

“Eleanor Rigby, died in the church and was buried along with her name, nobody came. Father McKenzie, wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave, no one was saved.” These final words remind us that we are all ultimately alone. Although in this case, Father McKenzie – whose life is as lonely as Eleanor’s – is at least there to see her over to the afterlife. There is ultimately someone there to see us through, even if it is after we have passed, if only to acknowledge our existence.

Then, there is the final chorus: “All the lonely people, where do they all come from?” This speaks to me and to all of us, I believe, at some stage of our lives, or a lot of stages in our lives. “All the lonely people, where do they all belong?” Where do any of us belong? It’s such a clever observation of the human condition and our need to find our place in the world. It addresses our belief that we only count if we are recognized by others…when the reality is discovering and being at one with our self-worth, however our life turns out. That is ultimately what it’s all about.

Kessler: Finally, Simon, why does this song appeal to you, personally?

This is a song that I very much identify with as an only child and as someone who lives on his own. Ultimately, we are all ‘lonely people,’ but what Paul McCartney (possibly together with John) tapped into is the ultimate loneliness of us all. Even if we are successful, we are unsure. If we are unsuccessful, we feel remote from those who seemingly find success easier. “Eleanor Rigby” is also about the lives we lead, despite the isolation we encounter in life. It is a song that speaks to so many people, even if they aren’t hardcore Beatles fans.

It’s a song that has always made me think. Very few of us get through life without anxiety and self-doubt. I do get very lonely. I suffer from anxiety and issues of self-worth, perhaps like so many of us in this Beatles family. And perhaps that’s why this family exists and why it is so successful…because it is one of the few places in life where we do belong, where we are amongst our own kind and where we can embrace individuality and encourage each other. It feels like this song was designed as a “shout out” to everyone looking for themselves.

We all have to go through life trying to exude a confidence we probably don’t have. Look at musicians like Adele, who suffer from imposter syndrome. I think we all suffer from imposter syndrome, unless we lack the humanity that anchors us to the reality of our short lives in the vastness of eternity. It doesn’t matter how much money you have in the bank, how good looking you are perceived to be, or what circles you move in – isolation is the biggest challenge we encounter in life, and it is easy to get lost. Look at the unfortunate people who are homeless and struggle to be seen at all by so many of us. Everyone deserves to be seen.

I wonder if Paul ever imagined that the fans of The Beatles would still be together after all these years and that the music and the legend of the group would create such a strong family bond? Yet, here we are. We are very lucky to have our Beatles family. It’s what keeps many of us sane and gives us a community to feel comfortable with. I think our Beatles community has a bond stronger than The Beatles ever anticipated. It has been the catalyst that unites us and helps us get through the tough times, and songs like “Eleanor Rigby,” for me, remind us where we all are and how lucky we are to have each other. A place where we can belong, be valued, and not feel so lonely.

Kessler: Simon, truer words were never penned! Thank you for being an integral part of this special look at “Eleanor Rigby”! We can’t wait to see you in just a few days at the New York Metro Fest for Beatles Fans!

For more info on Simon Weitzman, HEAD HERE or follow him on Facebook HERE or on LinkedIn HERE

For more information on Jude Southerland Kessler and The John Lennon Series, HEAD HERE