Side Two, Track Four

Calling ‘Dr. Robert’

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Steve Matteo

This month, the Fest for Beatles Fans Blog enjoys a closer look at Revolver’s “Dr. Robert.” Jude Southerland Kessler, our Fest Blogger and author of The John Lennon Series works hand-in-hand with Steve Matteo, author of Act Naturally: The Beatles on Film (2023), Let It Be, and Dylan to examine a Lennon song that has frequently been brushed aside as “a minor creation.” As Jude and Steve dig into the music and lyrics of this tongue-in-cheek creation, here’s hoping we all uncover some new insights into the story behind the song, the composition, and the recording techniques.

And we can’t wait to see each and every one of you at the Hyatt Regency O’Hare for the Chicago Fest for Beatles Fans, August 9-11! The lineup is too good to miss! Get your tickets and get ready for the time of your life!

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 17 April 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time Recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 10.30 p.m.

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 74)

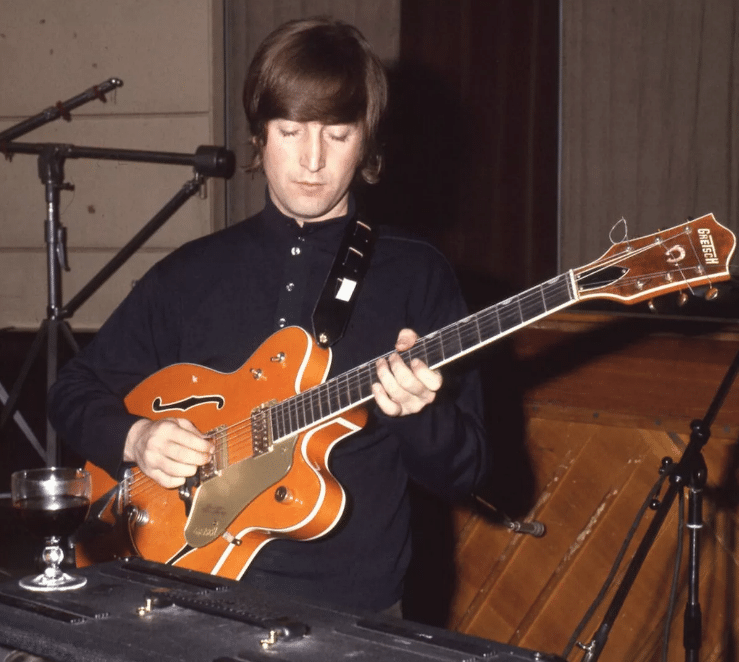

On this day: The Beatles recorded their backing track with John on his 1961 Fender Stratocaster electric guitar with synchronized tremolo (or possibly his Epiphone ES-230TD Casino electric guitar), Paul on his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass (which he was using more and more frequently in studio, when he could sit down), George on maracas, and Ringo on his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drums. As per their “now standard” method of recording, they first performed several rehearsal takes (not numbered) and then recorded seven actual takes, proclaiming seven as “best.”

Then, onto take 7, the boys made several superimpositions: John on the Mannborg harmonium (the studio’s), George on guitar,* and Paul on the studio’s Steinway “Music Room” Model “B” Grand Piano. (Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 123)

*I wrote to Jerry Hammack to ascertain which guitar George was using, and he graciously answered me: “George was working with a 1961 Fender Stratocaster with synchronized tremolo, 1964 Gibson SG Standard with Gibson Maestro Vibrola vibrato, or a 1965 Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino with Selmer Bigsby B7 vibrato during this period, and could have used any of these on his work. With this album and Pepper, the Casinos were certainly getting most of the attention.”

Hammack also tells us that at this point, “Dr. Robert” “…clocked in at 2:56” but “would be edited to 2:13 during remixing.” Sincere thanks to Jerry for helping with the Fest blog each month!

Second Date Recorded: 19 April 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time Recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 12.00 a.m.

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 74)

On this day: Since most of the work on “Dr. Robert” had been completed on the 17th, all that was left to do was capture the vocals from John and Paul…which they did. Later that same evening, a remix was done to thicken both those vocals and George’s guitar work.

Sources:

Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 75, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 218, The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology, 209, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 121-123, Womack, Sound Pictures, The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, 57, Harry, The Ultimate Beatles Encyclopedia, 209, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 12, Gould, Can’t Buy Me Love, 361-362, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 215, Turner, Beatles ’66, 157-159, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 114, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 344-345, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 173-174, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 227-228, Riley, Tell Me Why, 194-196, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 158-159, O’Toole, Songs We Were Singing, 113-115, Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia, 231, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 122-124, Spizer, The Beatles From Rubber Soul to Revolver, 221, Miles, The Beatles Diary, Vol. 1, 239, Shotton, John Lennon In My Life, 122, and Sheff, The Playboy Interviews (1981 edition), 152-153.

What’s Changed:

- A Thinly-Veiled Reference to Drugs – For years, Brian had sternly admonished The Beatles to remain “palatable to the mothers and fathers of teens everywhere.” And as such, the boys had not felt free to express opinions on anything, especially when it came to politics or the Vietnam War. Furthermore, Brian had asked the boys to present “a wholesome image,” eschewing cigarettes at press conferences or photo shoots. And through most of 1963-1964, John, Paul, George, and Ringo had reluctantly complied.

However, by the 1965 North American Tour, those old prohibitions were slip-sliding away. Indeed, the songs of late 1965’s Rubber Soul spoke frankly about difficult topics. They addressed marital infidelity (“Norwegian Wood”), a possible liaison with a rising film star (“Drive My Car”), the dissolution of John’s marriage (“It’s Only Love”), and the complications inherent in adult relationships (“You Won’t See Me” and “I’m Looking Through You”). Even The Beatles’ jaunty single, “We Can Work It Out/ Day Tripper” spoke frankly about love affairs that didn’t go smoothly or finish well.

Now, in the spring of 1966, John penned “Dr. Robert,” a light-hearted ditty about a doctor whom you could ring for drugs…and not cough syrup or any ordinary prescription. And the “rush” that John felt in penning a song like this was the knowledge that to “the Establishment” (Brian included) harmonizing about illegal drug usage was still very much taboo! In his book John Lennon In My Life, John’s lifelong friend Pete Shotton wrote, “When John played me the acetate of ‘Dr. Robert,’ he seemed beside himself with glee over the prospect of millions of record buyers innocently singing along.” (p. 122) Much like singing the “tit-tit-tit-tit-tit” backing chorus to “Girl,” the theme of “Dr. Robert” and his little black bag intrigued John and the lads because it felt quite naughty.

I was a tad surprised to find that in 100 Best Beatles Songs, Spignesi and Lewis rated “Dr. Robert” as #73. However, their explanation soon set me straight. They wrote, “Prior to Revolver…The Beatles…wrote about romance and relationships…Suddenly, with one album, their focus changed. Confiscatory taxes, the alienated and the lonely, laziness, consciousness, the afterlife, and lest we forget, yellow submarines were all topics on Revolver. And then, on this same album, came ‘Dr. Robert,’ which was about (blimey!) recreational drug use. The message was clear: ‘We’ve changed. Either get on board or get out of the way.’ And most of us went along happily for the ride.” (p. 227) Yes, indeed, in 1966 the times they were a-changing for The Beatles…and for us. And as we changed, they changed (or vice versa). The Beatles constantly evolved, and “Dr. Robert” is evidence of that.

- A Slathering of Humor – Though most listeners never comprehended it, in “Dr. Robert,” John Lennon was happily “takin’ the mickey” out of us all. He applied Lennonesque humor so subtly and with such finesse, that few realized that the heavy sound of the harmonium on the “Well, well, well, you’re feeling fine” bridge – backing those comforting words spoken by the goodly Dr. Robert – washed the words of the healer in a saintly soundtrack. When Dr. Robert spoke, it sounded exactly like a hymn offering salvation!

And why not? The healer was, John told us, the sort of doctor who “day or night will be there any time at all.” He’s the kind of physician who “will do everything he can – Dr. Robert!” From Dr. R’s “special cup” to his meds that would “pick you up,” the incomparable Dr. R had a unique way to “well, well, well make you.” You can almost see The Beatles cutting their eyes at one another and snickering.

Clearly, the boys were in on the joke. But actually, so were we, albeit unwittingly. In Tell Me Why, Tim Riley refers to the track as a “penetrating satire,” and he says that John’s biting humor “implicates not only the doctor and his ‘patients’ but the listener who gets seduced by the song’s tease as well.” (p. 123) This clever “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” creation casts us all under the spell of the sympathetic and edgy Dr. Robert.

A Fresh, New Look:

This month we’re privileged to have journalist and author Steve Matteo join us for the “Fresh New Look” segment of our Fest Blog. Steve was part of the 2023 Chicago Fest for Beatles Fans and the 2024 New York Fest at the TWA Hotel. He is the author of Let It Be and Dylan and his 2023 release, Act Naturally: The Beatles on Film. Steve has also written for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Rolling Stone, Spin, Elle, and Salon. We’re looking forward to having Steve and his wife, Jayne, join us again for the Chicago Fest 2024 and we’re excited to hear his reactions to “Dr. Robert,” the fun “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” creation by John Lennon and the boys.

Jude Southerland Kessler: Steve, welcome to the Fest Blog and thank you very much for taking time out of your busy schedule to share your expertise with us. Steve, in the spring/early summer of 1966, The Beatles and George Martin (now an independent producer) returned to EMI Studios not merely as musicians but as artists and innovative technicians. Using “every trick in the book” (as Lou Christie would sing years later) they employed unique instruments, recording techniques, and even outside musicians to create precisely the effects they sought. Although it’s not as obvious with this song as with others, “Dr. Robert” is layered with intentional sounds and stylings that afford the listener samples of a stressed life eased by Dr. Robert and his medicine show. How does John Lennon utilize his guitar, the vocals, and George Martin/Geoff Emerick’s recording techniques to achieve this aural imagery?

Steve Matteo: “Dr. Robert,” released at a significant time in the history of the recordings of the Beatles, is a song often discussed because of its lyrical story. The group’s previous album was Rubber Soul, the first album that throughout showed off the new sounds and textures they were exploring in the studio. The album broadened the canvas of the recording studio and introduced new colors and shadings that made the group’s already extraordinary songs even more vivid. After Rubber Soul and just before they began recording Revolver, they recorded the single “Paperback Writer” and the B-side “Rain.” While lyrically “Paperback Writer” was a poppy story of a writer of dime-store novels, it had guitar and vocal effects that were quite new. “Rain” was even more musically adventurous. On what may be the group’s best B-side, the interplay between McCartney’s bass and Starr’s drums is some of the most exciting playing of any track from the group and illustrates the cosmic musical relationship the group’s rhythm section created.

The vocals, however, are primarily what make “Dr. Robert” so musically memorable. The vocals on the track utilize ADT (Automatic Double Tracking) technology more than the other tracks on this album that is filled with it. Also, some of the vocal harmonies when the group sings “Well, well, well, you’re feeling fine” sound like a Greek chorus. It is here where the druggy theme of the song is most pronounced, but also shows how the group is clearly having fun with the subject matter. Adding to the decadent debauchery of the song’s milieu is some spacey Mannborg harmonium keyboard work by John Lennon, the main writer of the song and lead vocalist. Musically the song is very simple and playful, belying its subject matter.

While the theme of the song, particularly the doctor in question, has been debated and speculated upon since its release, another potentially key influence on the songwriting may have been overlooked. It’s hard to tell the exact spark that influenced Lennon to write the song, but one possibility is intriguing and highly plausible. The Rolling Stones had recorded a song called “Mother’s Little Helper,” which was the lead track on the group’s Aftermath album, released on April 15, 1966.

The recording of “Dr. Robert” began on April 14. There’s certainly a good chance Lennon heard the album long before its official U.K. release. There is a much-viewed photo of McCartney in the recording studio closely examining the back cover of Aftermath, with his reading glasses on and holding onto his Rickenbacker bass guitar. With “Mother’s Little Helper,” rather than reflecting the burgeoning drug culture of the youth of the day, Jagger was writing about someone with parental and adult responsibilities dealing with the stress by taking pills.

“Dr. Robert,” Lennon’s first song to address the theme of drugs, rather than glorifying them, tells of a doctor available to the pampered and well-connected denizens of the demi-monde of the day. Unlike “Mother’s Little Helper,” the song doesn’t, for the most part, have a dreamy or spacey quality. While “Mother’s Little Helper” has a terse, almost gritty rock’n’roll edge, “Dr. Robert” is a jaunty little tune. It is a whimsical tale with the kind of light touch that appeared on the surface of Lewis Carroll’s “Alice” books, which were filled with drug references – literature Lennon was all too familiar with and fond of since he was a child.

Kessler: Steve, Beatles music experts and biographers have bandied about the identity of the infamous Dr. Robert. Some, like Hunter Davies, point to dentist John Riley who, without permission, gave George and John LSD in their coffee in the spring of 1965. Some point to London’s Robert Fraser. Most aver that Dr. Robert is New York’s famed Robert Freymann (Freeman or Frieman in other sources) who served as “healer” for the stars; some go so far as to claim that John was one of his clients. However, for those like you who know The Beatles’ harried schedule during those few days in which The Beatles were in New York during February of 1964, late August of 1964, mid-September of 1964, and mid-August of 1965 when they returned to play another “Ed Sullivan Show,” perform in Shea Stadium, and host celebrities in their suite the following day, there was absolutely zero time for John (and/or The Beatles) to trek over to see this supposed Dr. Robert. And there is no record of his presence in their suite, though myriad others are catalogued. Paul states that they have merely heard about the doctor and are writing this song based on that knowledge. In The Beatles Anthology and later in his Playboy Interviews, John Lennon stated that he consistently carried and administered the drugs for the band and – like almost all of his other songs – this song was written about him; he was Dr. Robert. What say you?

Matteo: It would appear the doctor in question initially was based on a doctor in New York who indeed did administer “vitamin” injections for his curious clientele. A more sinister reality of the situation may have been the doctor giving amphetamine shots to wealthy socialites, the famous and the infamous. Various doctors have been named as the subject of Lennon’s song, even though Lennon himself may not have been aware of exactly who the doctor was and just what he was doing. Many sources, as Jude pointed out in the “What’s New” segment, claim the real-life doctor in question was Dr. Robert Freymann, a German-born doctor who, at the time of the writing and recording of the song, was 60 years old and whose office was located at 78th Street, in Manhattan, on the tony upper east side. Interestingly, in the film Ciao Manhattan, produced by Andy Warhol, there is a character named Dr. Charles Robert, who was likely based on the real Dr. Freymann, or even on Lennon’s song, since the film came out in 1972. In 1972, the real Dr. Freymann was still practicing medicine and was eventually expelled from the New York State Medical Society for malpractice in 1975.

What makes things even more confusing is that in Manhattan in the mid- to late-60s and early-70s there were many so-called “Dr. Roberts” offering a seamlessly endless cornucopia of potions to cure whatever ailed one. This doctor is the dark and destructive side of the drug culture, not those experimenting with marijuana or LSD who were seeking a more spiritual enlightening, although LSD and amphetamines could be equally lethal with enough use. It’s easy to read many other meanings (and doctors, real and imagined) into the song and on any given day, Lennon may have offered his own varying answers to what it was all about. It is, of course, not the only song on the album that has drug references, just the first he had written.

Prior to Revolver, “Rain” may have been influenced by drug use, but didn’t directly address drugs in the song’s lyrics. The other songs on the album about drugs, directly or indirectly, are “I’m Only Sleeping,” “She Said She Said” and “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Paul’s songs that had direct or indirect drug references are “Yellow Submarine” and “Got to Get You Into My life.” All of them share an obliqueness when addressing drugs, but all have drugs as a key component, whether musically or lyrically or both. There is also the question of whether the songs were simply influenced by the drug culture, or written under the influence.

Lennon was always a fan of double-entendres, as were The Beatles, especially the naughty schoolboys that still lurked in the four. “Dr. Robert” doesn’t so much have double-entendres as it includes lyrics that don’t specifically spell out the story of the song’s title character. It’s a song for those in the know, who get the wink-wink wordplay. The lyrics that most spell out who “Dr. Robert” is and what his function was and how Lennon slyly laid it out are: “If you’re down, he’ll pick you up/Doctor Robert/Take a drink from his special cup.”

Kessler: Steve, as I mentioned in the “What’s Changed” segment of the blog, in Spignesi and Lewis’s book, 100 Best Beatles Songs, “Dr. Robert” is rated at #73 , above such songs as “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Get Back,” and “Michelle.” How do you feel about the song’s ranking and the song itself?

Matteo: It’s difficult to rate “Dr. Robert.” In the context of Revolver, arguably the group’s best album, it may not be considered one of the group’s best songs or recordings. Among their entire catalog, it probably fares better. As is always the case, individual tracks from The Beatles that may not be considered among their best would probably rank pretty high against those from many other artists and certainly better than what passes for hits on the charts these days.

For more information on Steve Matteo, HEAD HERE

Follow Steve on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter

For my review of Steve Matteo’s book, Act Naturally: The Beatles on Film, HEAD HERE

Join Steve and Jude at the Fest for Beatles Fans, Aug. 9-11 at the Hyatt Regency O’Hare!!