The Fest for Beatles Fans hopes you’ve been enjoying some fresh, new perspectives on the Rubber Soul songs you’ve known and loved since 1965. Our goal is to give each song a new look, and if you like that perspective, wonderful! If you have an interesting viewpoint of your own on the song, please share it! And if you’d like to continue listening to the song as you always have, shine on! We’re enjoying re-examining these classics (after 50 plus years) with some of the world’s most revered Beatles music experts and uncovering fresh perspectives to enrich what we know. And…we’re so glad to have you along!

This month, we’re “deep diving” into “Nowhere Man” with John Lennon Series author, Jude Southerland Kessler, and with noted historian, Beatlefan Executive Editor, and author, Al Sussman.

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: First attempt on 21 October, with a complete remake on 22 October (followed by superimpositions and mixing on the 25th and 26th of October as well as 22 November)

Studio: EMI Studios, Studio 2

Tech Team:

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Norman Smith

Second Engineers: Ken Scott (and according to Margotin and Guesdon, Ron Pender)

Instrumentation and Musicians:

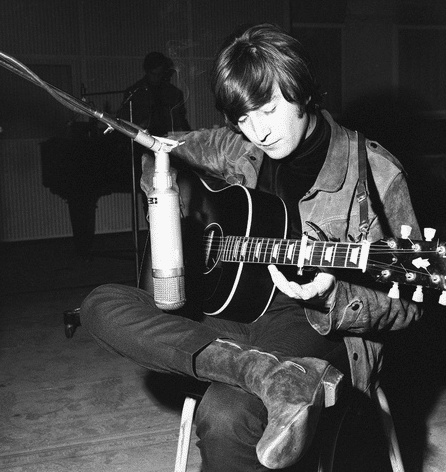

John Lennon, the composer, sings lead vocals and plays his 1964 Gibson J-160E acoustic guitar for the rhythm track and in superimposition, plays lead (with George) on his Fender Stratocaster

Paul McCartney, sings backing vocal and plays 1965 Rickenbacker 4401S bass

George Harrison sings backing vocal (McCartney and Harrison are double-tracked) and in superimposition, plays lead (with John) on his 1961 Fender Stratocaster

Ringo Starr plays one of his two Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum kits

Sources: Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 203, Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 65, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 201, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 284-285, Winn, Way Beyond Compare, 366-367, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, 78-80, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 91, Riley, Tell Me Why, 161-162, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 52-53, Miles, The Beatles’ Diary, Vol. 1, 217, Everett, The Beatles as Musicians: the Quarry Men Through Rubber Soul, 322-324, and Coleman, Lennon, 298-299.

What’s Changed:

- The Definition of a “Rock Song” – “Rock songs did not usually open this way.” So say Stephen Spignesi and Michael Lewis, referring to the exquisite opening of “Nowhere Man,” a brilliant bit of three-part a cappella harmony from Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison. Ranking the song as the #13 Best Beatles Song of all time, they explain that the tight vocal harmony sends chill bumps even before the lyrics begin to tug at our hearts. And although this singular sound was difficult to reproduce live, The Beatles chose to perform the haunting track on their 1966 tour, singing it in their final concert at Candlestick Park. But on that October night in 1965 when the boys recorded this stirring and unique introduction, they redefined the essence of “rock song” in one echoing moment. Mark Lewisohn sums up the work done in studio on 22 October as “A fine piece of work.” (The Beatles Recording Sessions, 65)

- The Birth of “Together, Alone” – Throughout the pandemic of 2020, the slogan “together, alone” resounded across the world. But that theme has its roots here in Lennon’s composition about shared loneliness. Later, in “Strawberry Fields Forever,” John would express the isolation of genius a bit differently: “No one, I think, is in my tree/ I mean, it must be high or low.” But no matter how John articulated it, Beatle John experienced life — utterly surrounded by co-workers, assistants, press men, business associates, and fans — in absolute seclusion. This isolation was nothing new, however. From childhood, his genius had always quarantined him; John was ever the “odd one out.”

- No Mere Love Song – Many Beatles music experts state that “Nowhere Man” is the first Beatles song that is not about love. And although, technically, that is true — since it is not a “he loves her,” “she loves him,” or “I love you” ballad — this song is about a much more pervasive, broad-sweeping love. All of The Beatles had experienced the loneliness of “a train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room.” But John knew that the loneliness they had endured (and what he had always experienced) could not be unique. And so, as Tim Riley points out: in “Nowhere Man,” John sang “for the unsung, for the people who have shut themselves off from life.” (Tell Me Why, 162) John took a very personal message and made it a universal love song. A powerful one.

- The Concept of Creating Somnambulantly – Paul had created “Yesterday” in a dream. Now in the autumn of 1965, John, who had struggled for hours to pen a new song for the emerging Rubber Soul LP, gave up in frustration and “went to have a lie down.” (Everett, The Beatles as Musicians, Vol. 1, 322) As he drifted off into a restful state, suddenly, the words to “Nowhere Man” sprang to life. John said, “Then I thought of myself as a Nowhere Man — sitting in his nowhere land,” (Spizer, Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 201) and the lyrics surfaced, “words and music, the whole damn thing!”(Everett, 322) By 1967, in his “I’m Only Sleeping,” John revealed that the practice of relaxing and letting go —“stay[ing] in bed” and “float[ing] upstream” (not downstream, which would indicate sleep) — allowed his muse to speak to him. Writing songs in bed became a standard Lennon practice. And it all began here.

- Experimentation with the “Jingle Jangle Sound” – Although The Beatles didn’t corner the market on the emerging “jingle jangle” sound of 1965 (The Byrds had already released “Mr. Tambourine Man,” in June 1965.), they were one of the first groups to employ it. Paul says that he pushed Engineer Norman Smith to create a “treble-y” guitar sound. When Smith said that all he could do was “put full treble on it,” Paul pressed for more saying, “Well, put that through another lot of faders and put full treble up on that. And if that’s not enough, we’ll go through another lot of faders…” (Spignesi and Lewis, The 100 Best Beatles Songs, 53) The result was the magical aura of “Nowhere Man,” which may seem commonplace today…but in 1965, this effect was unique and enchanting.

A Fresh, New Look:

Recently, we were honored to be able to talk with distinguished historian, Al Sussman, about “Nowhere Man.” Al is the Executive Editor for Beatlefan magazine and has for many years been an integral part of The Fest for Beatles Fans. He is also the author of Changin’ Times: 101 Days That Shaped a Generation and was a contributing author to Bruce Spizer’s The Beatles Finally Let It Be, The Beatles Get Back to Abbey Road, The Beatles and Sgt. Pepper: A Fan’s Perspective, and The Beatles White Album and The Launch of Apple. Here are Al’s insights into John Lennon’s honest and heartfelt 1965 ballad, “Nowhere Man.”

Jude Southerland Kessler: Al, journalist and Beatles friend, Ray Coleman, in his book, Lennon, says that in John’s 1965 classic hit: “The Nowhere Man is an impotent, hollow symbol of the Swinging Sixties.” And similarly, Steve Turner in A Hard Day’s Write says that “Nowhere Man” was interpreted by some as “a comment on the erosion of belief in modern society.” Please tell us about the historical backdrop of 1965 that fueled this solemn portrait of an empty, vacuous world.

Al Sussman: A less-oblique, more directly personal song than “Nowhere Man” is Brian Wilson’s “I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times,” which was written around the same time as “Nowhere Man” and appears on the Beach Boys’ classic Pet Sounds album. Living in the hothouse atmosphere of the mid-60s was not easy, particularly for a still-young man in a leadership position in what John later called “the greatest show on earth/For what it was worth.”

With an ongoing war in Vietnam, racial unrest not just in the U.S. but in England, too, an emerging drug culture, and a media hungry for The Beatles’ views on all of this, it was easy to believe in the “erosion of modern society.” Much has been written about how The Beatles had each other to get them through the madness that surrounded them but, by mid-1965, the only one still residing in Swinging London was Paul. The others had all bought homes in the stockbroker-dominated suburbs. So, living in a mansion and in a marriage that he felt wasn’t giving him fulfillment, John was truly isolated, and his increasing intake of pot and other drugs wasn’t helping. Hence, his feeling that he was “A real nowhere man/Sitting in his nowhere land/Making all his nowhere plans for nobody.”

Kessler: In Tell Me Why, Tim Riley observes that in “Nowhere Man,” John Lennon reminds us that “no one can make it through life’s difficulties alone…the best crutches are other people.” (p. 162) What were some of the personal difficulties with which John struggled in 1965? What circumstances made him feel like “a real Nowhere Man living in his nowhere land”?

Sussman: It’s interesting to consider that, in 1965, John Lennon wrote “Help,” “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” and “Nowhere Man,” all of which reflected the isolation he was experiencing in his new suburban life away from “the eye of the hurricane.” It was John who later called this his “fat Elvis” period, and not just for the few extra pounds he had put on. Of course, it’s a mark of the complexity of the man and the composer that he also wrote “In My Life,” “It’s Only Love” and, yes, “Norwegian Wood” during this same period. Not being as natural a pop craftsman as Paul, it could take some cajoling from those “best crutches,” but the isolation seemed to inspire one of John’s finest composing periods.

Kessler: I know you really like this song, Al. What elements make this song one of your favorite Beatles numbers? Is it the music, the lyrics, the message, all of the above…or something else?

Sussman: I had very much been a fan of the John/Paul/George three-part harmonies on songs like “This Boy” and “Yes It Is” and, during ’65, I’d become very attached to the emerging folk-rock sound. So, when I first heard “Nowhere Man” on WABC in New York, when they briefly played the four tracks from the British Rubber Soul not on the American edition, I instantly fell in love with the song. I loved the three-part harmony vocals and the background vocals and the Byrds-influenced instrumentation.

Frankly, I could also relate to John’s lyrics, even as a 16-year-old. And I was disappointed, when It was released as a U.S. single in Feb. 1966, that “The Ballad of the Green Berets” kept “Nowhere Man” from continuing the string of Beatles No. 1 singles. That autumn, as a high school junior, I took a Modern Communications course and, at one point, the teacher had us bring in lyrics to a popular song of the time. Most of the kids in the class didn’t take it very seriously and brought in lyrics for typical love songs of that moment (“I’m Your Puppet”), but I brought in “Nowhere Man,” even though, at that point, I didn’t know the real meaning behind it. All these years later, “Nowhere Man” is still among my top five favorite Beatles songs, and it’s aged exceptionally well.

Kessler: What would you like to share with us about “Nowhere Man” that we haven’t discussed in this blog?

Sussman: Younger fans have somehow gotten the impression that the reason why “I’ve Just Seen A Face” and “It’s Only Love” were added to the U.S. Rubber Soul, was so the album would sound more folk-rock. Frankly, the middle-aged big band/Sinatra-philes who were running American record companies in the mid-60s wouldn’t have known folk-rock if it hit them in the face. The two most folk-rock-esque songs on the U.K. LP were George’s very Byrds-derived “If I Needed Someone” and John’s “Nowhere Man” — neither one of which made the Capitol album.

Thanks for this. Rubber Soul was an important influence on me at that time and recetnly I wrote a poem about a friend of mine and me and these influences and if you don;t mind I share it with you from by blog:

https://christopher-black.com/2019/01/02/to-a-friend/

To A Friend

You walked in flowered fields with me

and talked of music, sex, philosophy,

of women, men, their loves and friends,

the fools who taught, our fated ends,

for we had read the strange Camus,

and even Dostoevsky knew,

but Kurosawa was our rage,

and Bergman was to us a sage,

as Ho Chi Minh fought our endless fight,

Guevara murdered was by night,

but while we wondered of our role

we found ourselves in Rubber Soul,

in Kerouac, Marx, and LSD,

for we were seventeen and free,

so road the rails, spent time in jail

wrote howling lines in one long wail,

drifting on a lonely sea,

of younger thoughts, of possibility,

but now you’re dead, some say it’s true,

or did you make it to Peru,

where once you promised me you’d go,

on reading lines from old Thoreau.