The Conclusion to our Fest for Beatles Fans Deep-Dive Into Revolver

By Robert Rodriguez

Thank you, one and all, for being with us for the last 18 months as The Fest for Beatles Fans delved into the multi-faceted, intricate work that is Revolver. What an exciting ride it has been working with such remarkable authors to uncover the many, many layers of this unparalleled work! We truly appreciate each one of these people taking time from their films, books, art, lectures, podcasts, webinars, and personal appearances to share their thoughts with us.

No one could close this lengthy study of Revolver better than the man who wrote THE book on Revolver, Robert Rodriguez. Until I read Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, I had no room in my heart for this album that sang about taxes, death, a doctor supplying drugs, and relationships in decay. At 15 years old, I didn’t understand a great deal of it, and I didn’t like it, much. So, I dismissed it for ages.

But Robert artfully opened the colorful, magical pop-up book that is Revolver for me and made it not only vastly comprehendible, but also majestic.

Here is Robert’s superb conclusion to our study and please…read his book for the full effect!

– Jude Southerland Kessler

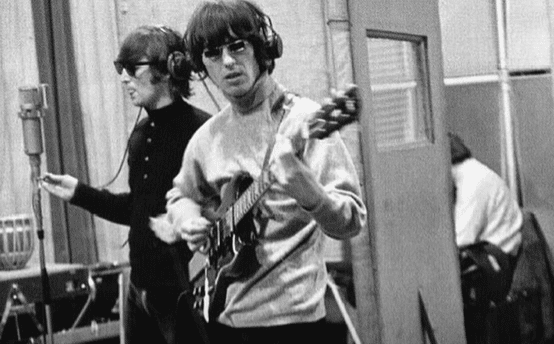

1966 was already shaping up as a departure from the previous three grueling years by the time The Beatles reconvened in the studio to begin work on their follow-up to Rubber Soul. 1963 had seen them parlay their first two hit singles for Parlophone into a best-selling album (and a follow-up), while 1965 was an echo of 1964: the year beginning with a new film and soundtrack album, followed by a world tour before releasing what had become a tradition for them, the holiday season long-player.

If overshooting their target goal to become a hitmaking entity had become a grind, there were plenty of signs along the way that artistic restlessness and aversion to formula was paying dividends. The Help! soundtrack album saw a leap forward with the recording of “Yesterday,” a distinctly non-beat group track that everyone must have recognized as a departure (and that they must have felt a degree of self-consciousness about, in that rather than showcasing it, they buried it on side two and then refused to release it as a single in the UK). This was followed in the autumn by Rubber Soul, which yielded further evidence of their embrace of studio craft. If heretofore their albums were primarily comprised of songs that could more or less be reproduced on stage, the baroque-sounding “wind-up piano” of “In My Life” or the exotically Eastern-sounding “Norwegian Wood” pointed away from what had been their custom.

They also were not creating in a vacuum. Informing their ambitions every step of the way was what was going on in the world of singles and albums, something they paid close attention to. This was evident at the beginning, with their embrace of early rock ‘n’ roll and subsequent disdain of much of what was popular coming out of Britain just before their own contract signing. Upon landing a record deal, they asserted the freedom to record their own compositions, an unheard-of demand for newbies with few cards to play.

But in fact, it was their in-house songwriting team that made them attractive to EMI in the first place. The company’s gamble on a long shot paid off dividends beyond their wildest expectations. In exchange, the label was willing to indulge the Beatles’ desire for freedom in the studio and their drive to widen the paradigm within their genre.

Each step they took creatively was a move past where they’d been before, but as long as they continue to score a million sellers, Parlophone could not quibble with this golden goose. The label could be demanding, and in this case, requiring some Christmas product when the band was fairly spent after such a busy year. But The Beatles recognized that the price for the latitude accorded them was to deliver. And despite a certain amount of scrounging to get Rubber Soul into shape, deliver they did, with John in particular cresting as a writer on that album. “In My Life” – “Norwegian Wood” – “The Word” – “Girl” – all stand among his finest achievements as a Beatle. (Less so “Run For Your Life,” a late clue to their past direction.)

Early in the new year, the group was signaling that they’d reached the end of the rope with certain constraints imposed upon them. Despite Brian Epstein’s admonitions to the contrary, they became increasingly frank in their exchanges with the press, no longer steering clear of controversy. Nowadays we live in a world where the PR team keeps a tight control over the artist’s image, but as with so much, The Beatles were sailing into uncharted waters.

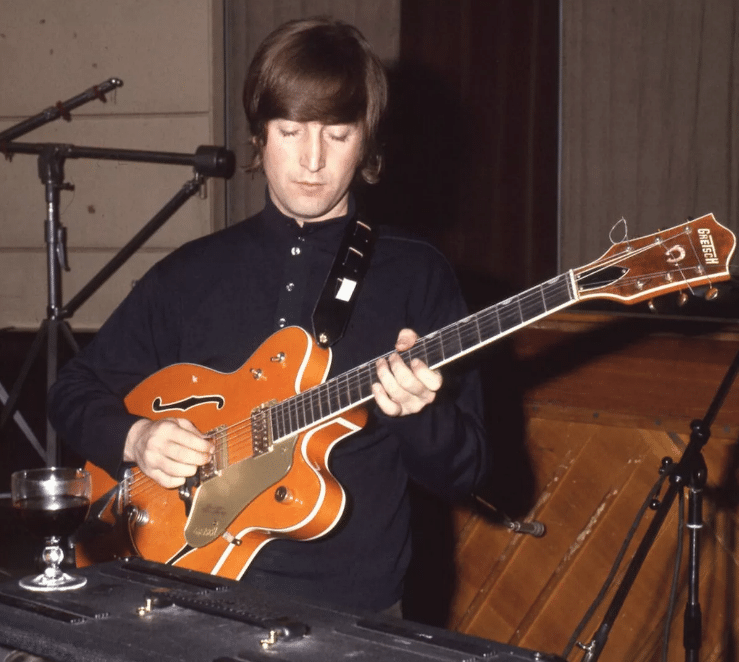

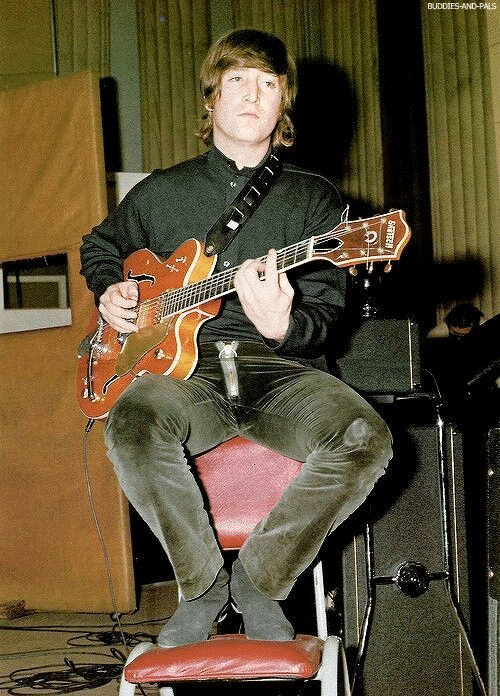

And there was the matter of their presentation. Photographer Robert Whitaker had been working with them since the Beatlemania days of 1964, more or less capturing them in flattering but conventional ways. Come March of ‘66, he was ready to take them in a more artsy and less commercial (to say the least) direction. The Beatles were certainly in the position to say no, but instead they embraced it. The ensuing outré shoot, nowadays known for yielding the so-called “Butcher cover,” was pretty dramatic evidence of a step toward their own artistic flexibility and away from the carefully cultivated moptop image that had sustained them to this point.

It came on the heels of the series of profiles given to journalist Maureen Cleave in the London Evening Standard earlier that month. Though not seeking controversy for its own sake the way a less disciplined public figure might, they certainly did not hold back from speaking their minds on an array of taboo subjects, including racism and religion.

What all this points to is they were chafing at the restraints they’d been subjected to thus far. Achieving and sustaining fame were no longer inhibiting considerations. They were moving toward describing themselves as artists, not simply “recording artists.” Though John was a few years away from calling everything he did art, it was clear that he and Paul at least saw what they were doing as something lasting and of value beyond the ephemeral pop chart considerations. They had earned a certain amount of liberty with their record label, and with sales no longer of utmost importance, they were now willing to act on any creative impulse they could conceive.

This period of early 1966 presented them with a gift of sorts: unlike their previous album project, they now had a bounty of time to produce a follow-up, owing to the circumstance of time budgeted for producing their third film going unused due to the lack of agreement on a script. Though it would have been fascinating to have seen what they would have come up with, knowing where their heads were at the time, our cinematic loss was their musical gain with the extra time they had to craft this release.

There is another aspect worth noting informing the direction that this particular project took, and with one Beatle in particular. As John would observe after the breakup, Rubber Soul was the pot album as Revolver had been the acid album. He needn’t have been describing himself, although that much was accurate. Really, he was speaking of a mindset informing the creation of the two respective releases. Whereas Rubber Soul possessed a chill vibe and more mature themes than previous releases, the expanded consciousness associated with the latter drug is readily apparent throughout the latter album, if the stylistic diversity and implicit psychedelic subtext is anything to go by. Lest we take this point too far, let’s underscore one thing right here: The Beatles were already extraordinarily gifted songwriters going back to the amphetamine years off the heels of Hamburg. Beyond the occasional weed or alcohol, they never deliberately worked in the studio under the influence (save the one occasion during the Sgt. Pepper sessions when John accidentally dosed himself, but it should be noted that no further work was done that night). All the drug talk here is meant to make the point that 1) It was definitely a part of their lives at this point and 2) Its use coincided with an undeniable expansion in their artistry. Any other direct correlation would be speculation.

So, all of this is meant to lay out what made Revolver a departure from previous work at the onset: 1) A demonstrable desire to advance their art; 2) A state of heightened consciousness that could in part at least be attributed to their recreational pursuits; 3) an unwillingness to play the game as they had to this point, and 4) more time to work on an album than they’d previously experienced.

If anyone is looking for more tangible proof of their intentions, look no further than the first session for this album, wherein they threw away everything they knew about making records. “Tomorrow Never Knows,” initially “Mark I,” would be the first fruit of their labors. We as listeners have been exposed to so much since August 1966 that it would be impossible for all but the people who were of age at the time to recognize what a leap into the future this recording was. The only artist that came close to concurrent experimentation would have been Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, hardly in the same lane as the Beatles. (Their debut album, Freak Out!, was released in late June 1966, coinciding with the end of the Revolver sessions. Though a commercial failure in the states, it did better in Europe and Paul was said to have been a fan, telling people it was an inspiration for Sgt. Pepper.)

Though US fans would have been familiar with full-blown Indian performances on the Capitol version of Help!, George’s “Love You To” presented this music as Beatles and not simply incidental music. This song showcased an early effort at following his bliss, something he would pursue with a vengeance following the end of touring later that year. Indian sounds had begun creeping into Western pop music the previous year, predating even “Norwegian Wood,” but no one had presented a fully formed piece of raga rock like this before.

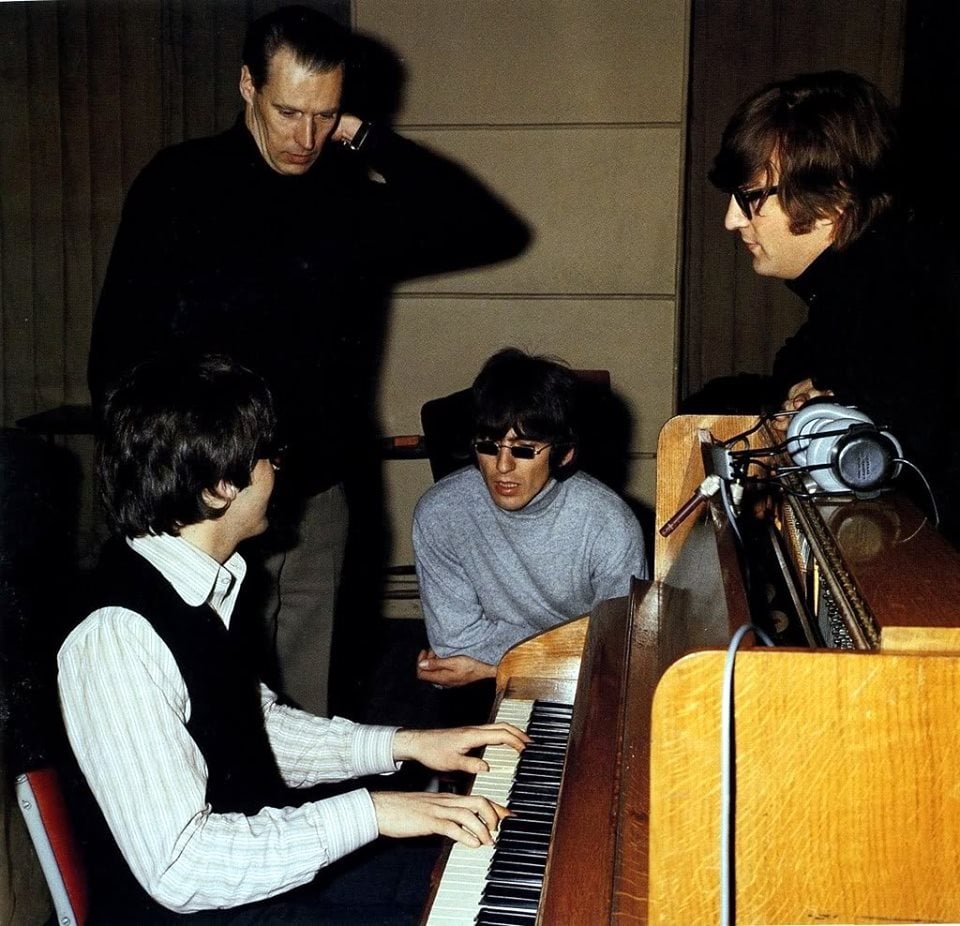

Since moving in with the Ashers in 1963, Paul had been undertaking an advanced course in cultural enrichment. Living in the heart of London (whereas his bandmates had moved out to the suburbs), he was also the sole bachelor and thus readily available to partake in all the happenings while Swinging London was the center of the artistic universe. This immersion encompassed everything from the fine arts, classical and modern, as well as the avant-garde and experimental. His familiarity with the latter tended to manifest not in his own compositions, but those of his bandmates: tape loops for John’s “Tomorrow Never Knows”; dissonance for George’s “I Want To Tell You”; Eastern-sounding lead guitar for George’s “Taxman.” (This was something Jeff Beck had been exploring with The Yardbirds, notably on “Heart Full of Soul” but also “Over Under Sideways Down.”)

But for his own compositions, Paul’s stretching out took the form of applying elements far beyond their beat group origins. “Eleanor Rigby” was a triumph on every level: George Martin’s dramatic string octet score was like nothing else heard in pop to that time. (The closest thing to it heard on top 40 radio that year may have been the similarly string-laden “Walk Away Renee” by NYC’s The Left Banke, released in July but actually recorded in March.) An egalitarian spirit resulted in the song’s social commentary lyrics (an element prompting no little resentment from John over Paul’s willingness to accept creative input from anyone who was around). But the song’s theme of universal loneliness was an atypical excursion into what had once been Bob Dylan territory. It laid out a problem but offered no comforting solution.

Indeed, Paul’s willingness to repurpose sounds associated with his peer artists could be found all over the album. “Good Day Sunshine” was directly inspired by the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Daydream,” while the exquisite “Here There and Everywhere” evoked the sound The Beach Boys had borrowed from The Four Freshmen. Brian Wilson (at least, among his band) had by this time scaled ambitions upward on a parallel path along with The Beatles (the Capitol iteration of Rubber Soul being a direct inspiration for their own breakthrough album, 1966’s Pet Sounds). Likewise, in their own way, The Byrds were quickly moving past their folk-rock origins to similarly assimilate Eastern ideas into their music, culminating with the modal improvisations of “Eight Miles High” – a single whose title may have evoked the drug culture but in fact was inspired by their flight to the UK. Here, they channeled Ravi Shankar not with sitar, but with the sound of a 12-string Rickenbacker, itself inspired by George in the first place.

Less directly precedented were two of Paul’s stylistic excursions heard on side two: the classically inspired “For No One” and the R&B shouter, “Got To Get You Into My Life.” The first one, with its elegant clavichord and tasteful French horn solo was dubbed “Baroque and Roll” by those who thrill in such labels. Not to be overlooked was the stark depiction of heartache in the lyrics; a subject Macca did not typically traffic in. Like “Eleanor Rigby,” there was no solace to be found here; it may be for its perceived “realism” that John declared it to be a particular favorite.

The latter composition featured an authentic soul horn section, an element that would regularly be featured in Paul’s solo work. It also possessed a clever double meaning lyric that worked as a love song as well as its true subject matter, pot (or acid, depending on the telling). If one needs any further evidence of how ahead of the curve The Beatles were in general, or this album in particular, consider this: “Got To Get You Into My Life” was issued as a single in the US one decade after its creation: not as a charming anachronism like “The Twist,” “Monster Mash,” or “Rock Around The Clock” but competing alongside the sounds of the day, including Silver Convention’s “Get Up and Boogie,” Thin Lizzy’s “The Boys Are Back In Town,” and Paul’s own “Silly Love Songs.” It peaked at number 7, which was two places higher than the remake by Earth, Wind and Fire two years later.

Returning for a moment to the subject of drugs again, it’s not hard to find the evidence of John’s infatuation at the time. In addition to the user’s manual for tripping depicted in “Tomorrow Never Knows,” we have his description of a bad trip in “She Said, She Said”; an advert for a friendly pill-pusher in “Dr. Robert,” and the more subtle expressions of his expanded consciousness presented in “I’m Only Sleeping” and “And Your Bird Can Sing.” The former song concerns itself with the joy readily attainable by slipping out of the fully conscious state of mind, while the latter advocated for finding peace of mind from the internal rather than the external. (This of course predated their fascination with the Maharishi’s teachings.)

George evoked his acid experience with “I Want To Tell You,” a song stating how his newfound insights left him inarticulate. Though psychedelic-themed, it featured a conventional arrangement with the aforementioned dissonance added. “Love You To” may indirectly reflect his LSD insights as he advised his listeners of the heightened awareness he had begun to acquire in the form of admonitions. One may observe that this became a less attractive quality well into his solo years, but here it is, tempered with an exciting arrangement and climactic finish. (To traffic in double entendres is undoubtedly more fun for the person doing it than it is for the reader, to be sure.)

Left undiscussed to this point is the Ringo vocal spotlight, the deceptively psychedelic “Yellow Submarine.” Like some of George’s more ponderous material, this tends to be a divisive one for fans. To hate on it would be to miss the point: it was, on one level, intended as a sing-along for children and with that modest goal, it hit the mark. But there’s certainly room in interpreting the lyrics to find evocative imagery and the deeper theme of a collective society living in harmony. What is most interesting nowadays is the recent revelation of the verses apparently initiating with John, rather than Paul. A work tape surfaced while archivists were putting together the expanded Revolver set, featuring John on acoustic guitar singing a structure very like the eventual verses, but much, much grimmer. It reads like a precursor to his Plastic Ono Band confessionals, declaring of his childhood, “no one cared, no one cared.” Had they continued down that particular path, perhaps the song would have been realized as another in the lineage of “I’m A Loser” and “Help!” But thankfully for Al Brodax, Heinz Edelmann and Ringo, the song was retooled into the form it is known today.

Revolver stands as a bold testament to imagination, vision and inspiration. With its breadth and depth, it was a feat of colossal daring that might have been received the same way the Magical Mystery Tour film was a year-and-a-half later: self-indulgent, messy, indecipherable. But The Beatles’ read on their audience, as always, was pitch perfect; they did not get too far ahead of themselves to lose their base. Crafting a collection wherein virtually every tune on it was a subgenre unto itself represented an unprecedented demolition of barriers. In less than a year, The Beatles would present to the world an album where they used an alter ego identity as a means of presenting a justification for diversity outside The Beatles’ existing paradigm. Perhaps they’d forgotten they’d already done it with Revolver, while dispensing with the mask.

It is practically impossible at this distance to grasp the audacity The Beatles must have possessed to lay this on the world. For some fans, it may have been a little dark or weird but their fellow creators were surely listening. The most imaginative minds in their field were most certainly inspired to break through some barriers of their own. Funnily enough, one of its detractors at the time was Ray Davies of The Kinks, who famously nitpicked the album with faint praise (“…at least it was recorded well”) when not calling parts of it “rubbish.” Let’s try to remember he was still in his twenties and not selling records in the same volume as those he would critique. His assessment has not aged well, and on the contrary, Revolver began to experience a well-earned second look of appreciation by the 1990s, perhaps informed by the UK iteration getting worldwide distribution on CD.

It was a fluke of history that Revolver arrived at a time that the public’s attention wasn’t ready to recognize this advance in their art. They still looked more or less the same as they had in the previous years, and their tours had become routine. The “more popular than Jesus” controversy surely knocked them off message in the media, with journalists more interested in taking John and the group down a peg or two than they were in expressing any curiosity in the groundbreaking music they just crafted. And then there was The Beatles themselves, who followed up the release six months later with the astonishing double-A side single, “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane.” After that nail-biting period of “Are they breaking up?” (there was no holiday release, after all) was answered by their new look and astonishing sound, the release of Sgt. Pepper was heralded unmistakably as an event in a way that Revolver‘s arrival wasn’t.

Revolver represents a revolutionary leap into the future, as well as risk-taking that took The Beatles – and their listeners – out of their comfort zone. For decades to come, it gave artists that followed permission to explore outside of existing paradigms. While Pepper was presented with a well-articulated concept (i.e. WE are Sgt. Pepper’s band, putting on a show), with the costumes to prove it, Revolver‘s cohesive framework was more subtle: “We’re The Beatles and we can do whatever that hell we want. Would you like to come along?”