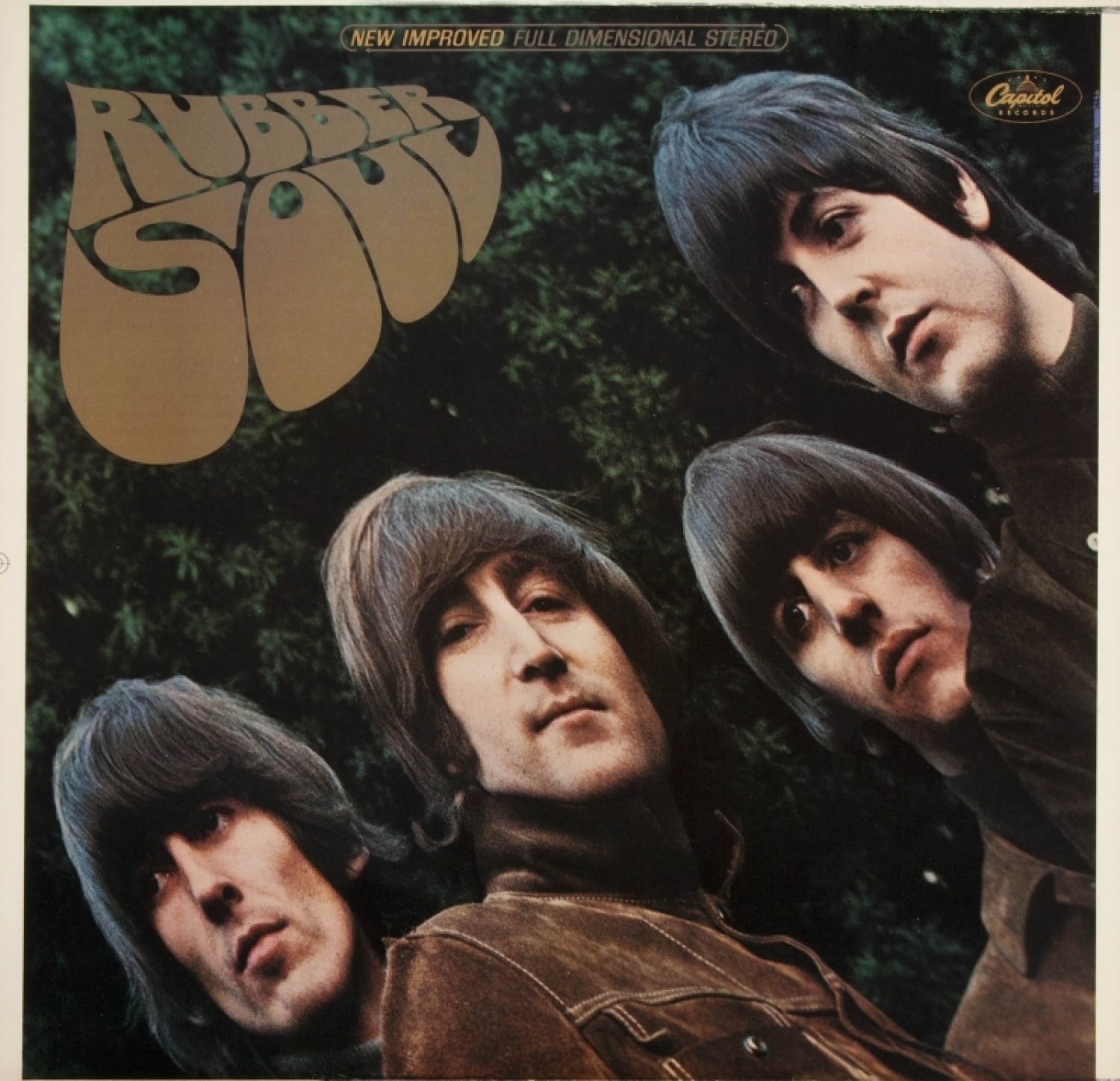

Rubber Soul

Side Two, Track Three

“In My Life”

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Susan Ryan

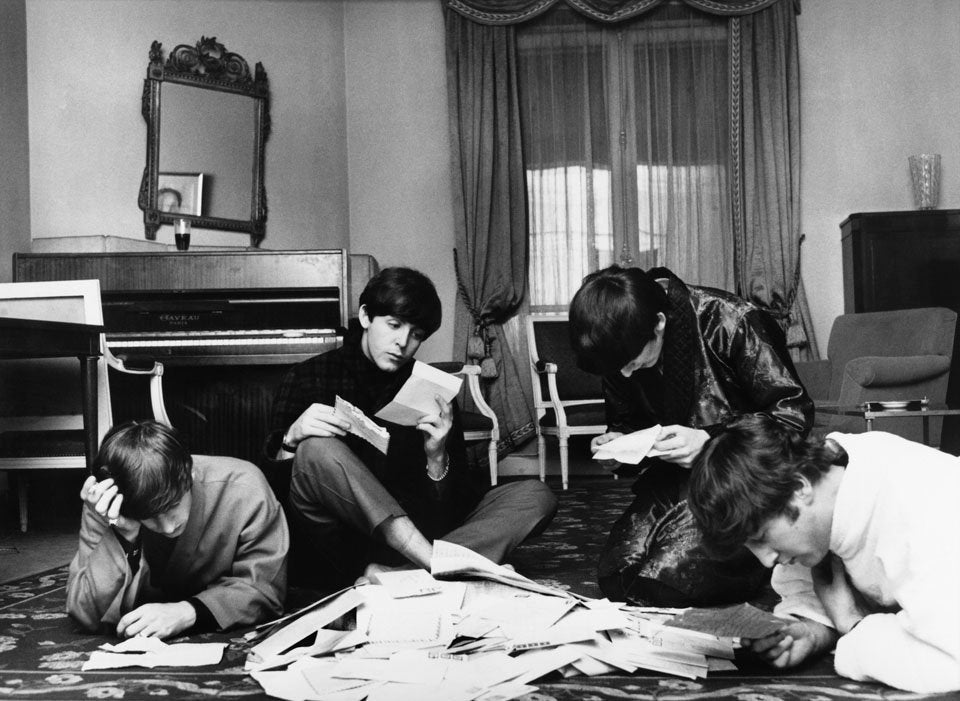

Throughout 2021 and the first few months of 2022, the Fest for Beatles Fans blog has been exploring some of the finer points of The Beatles’ innovative 1965 LP, Rubber Soul. This month, a lifelong friend of the Fest, Susan Ryan, joins Jude Southerland Kessler, author of The John Lennon Series for an in-depth consideration of “In My Life.” Susan is the co-author of The Beatles Fab Four Cities, a new release thoroughly exploring the lives of The Beatles in Liverpool, Hamburg, London, and New York City. Susan is also an experienced New York City Beatles Tour guide and the owner of Fab Four Walking Tours. In her role as a noted public speaker, Susan has served as Emcee for Beatles at the Ridge and The Fest for Beatles Fans. Susan and Jude hope you enjoy this “fresh, new look” at Lennon’s masterpiece, “In My Life.”

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded:

18 October 1965 – The Beatles recorded the base track for the song: the two guitars, bass, and drums in three takes. On Take 3, John recorded his double-tracked vocals; Paul and George added backing vocals.

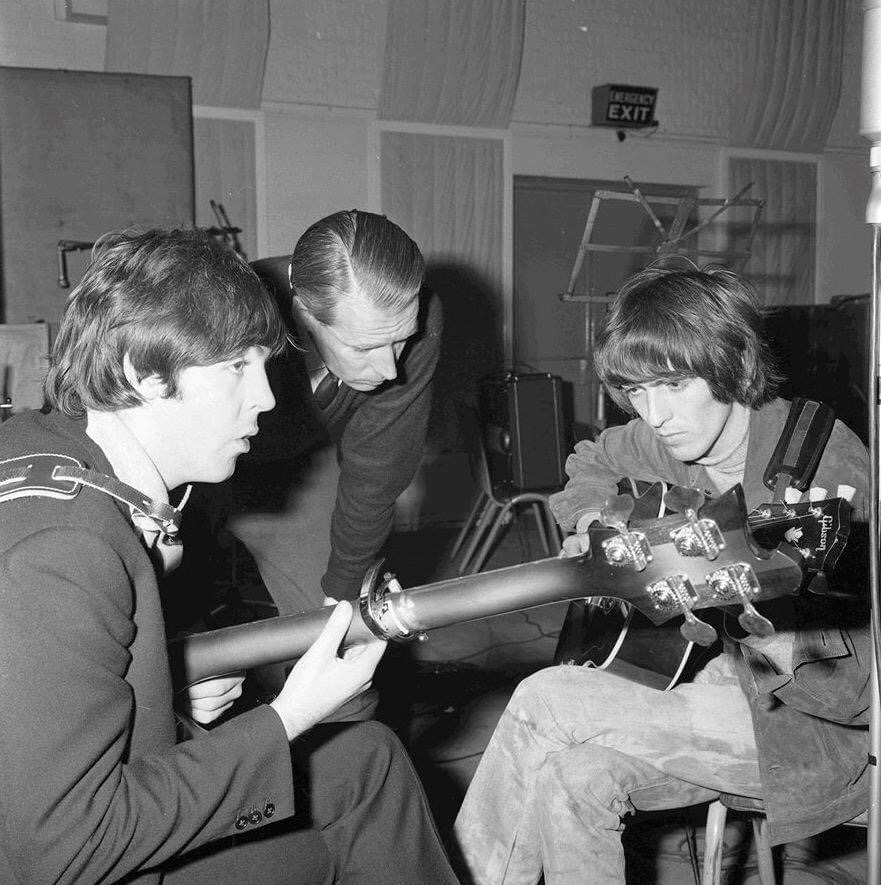

22 October 1965 – As per John’s request for “something baroque,” George Martin recorded an original piano solo for what John referred to as the song’s “middle eight.” Martin did this by playing half-speed on a normal piano and then speeding it up to create the sound of a harpsichord.

Studio: Both recordings took place in EMI Studios, Studio 2

Tech Team

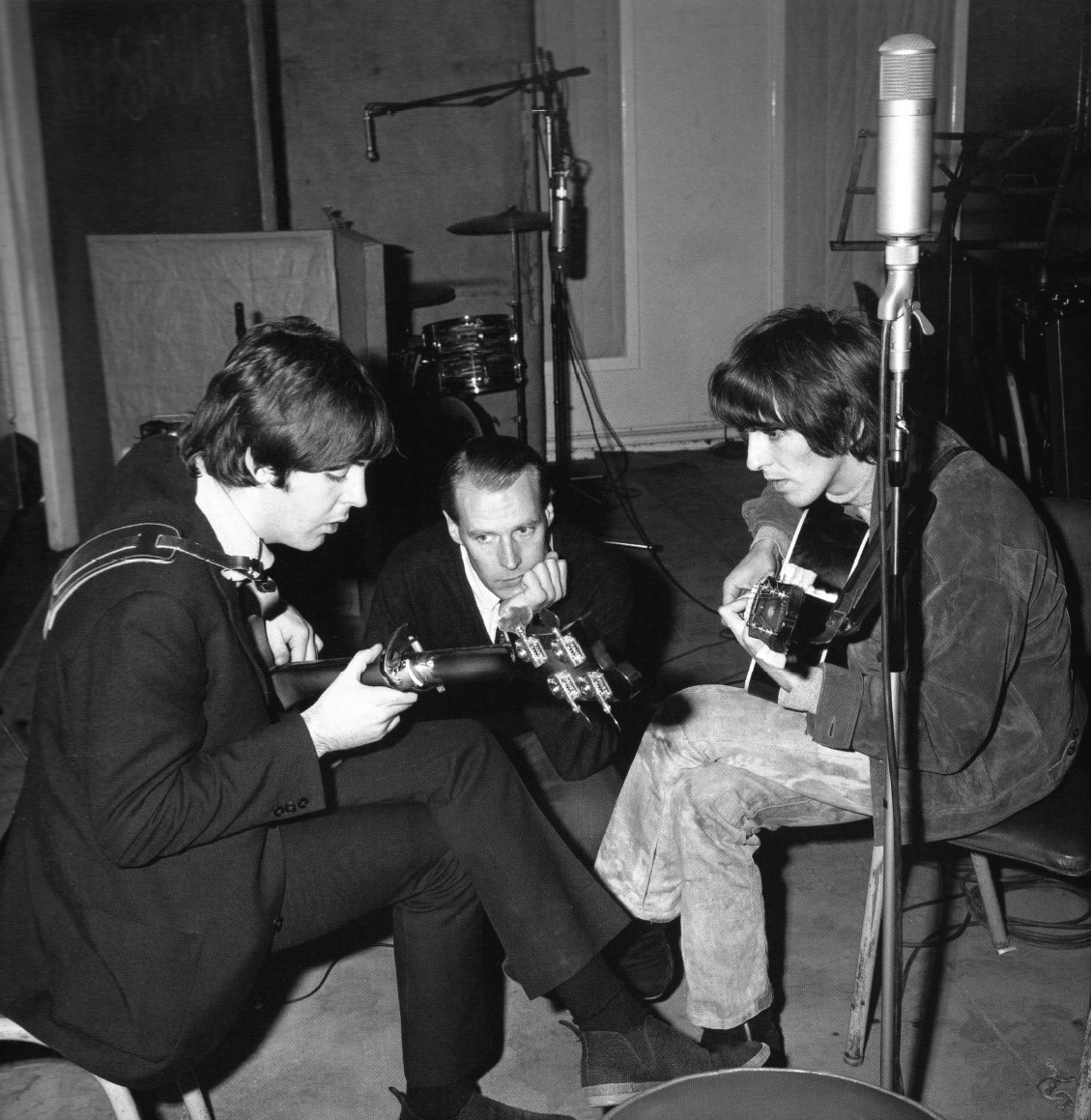

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Norman Smith (and according to some sources, Ron Pender)

Second Engineer: Ken Scott

Stats: Recorded in only four takes. “Best” take was Take 4. However, a plethora of overdubs completed the song in later sessions.

Instrumentation and Musicians:

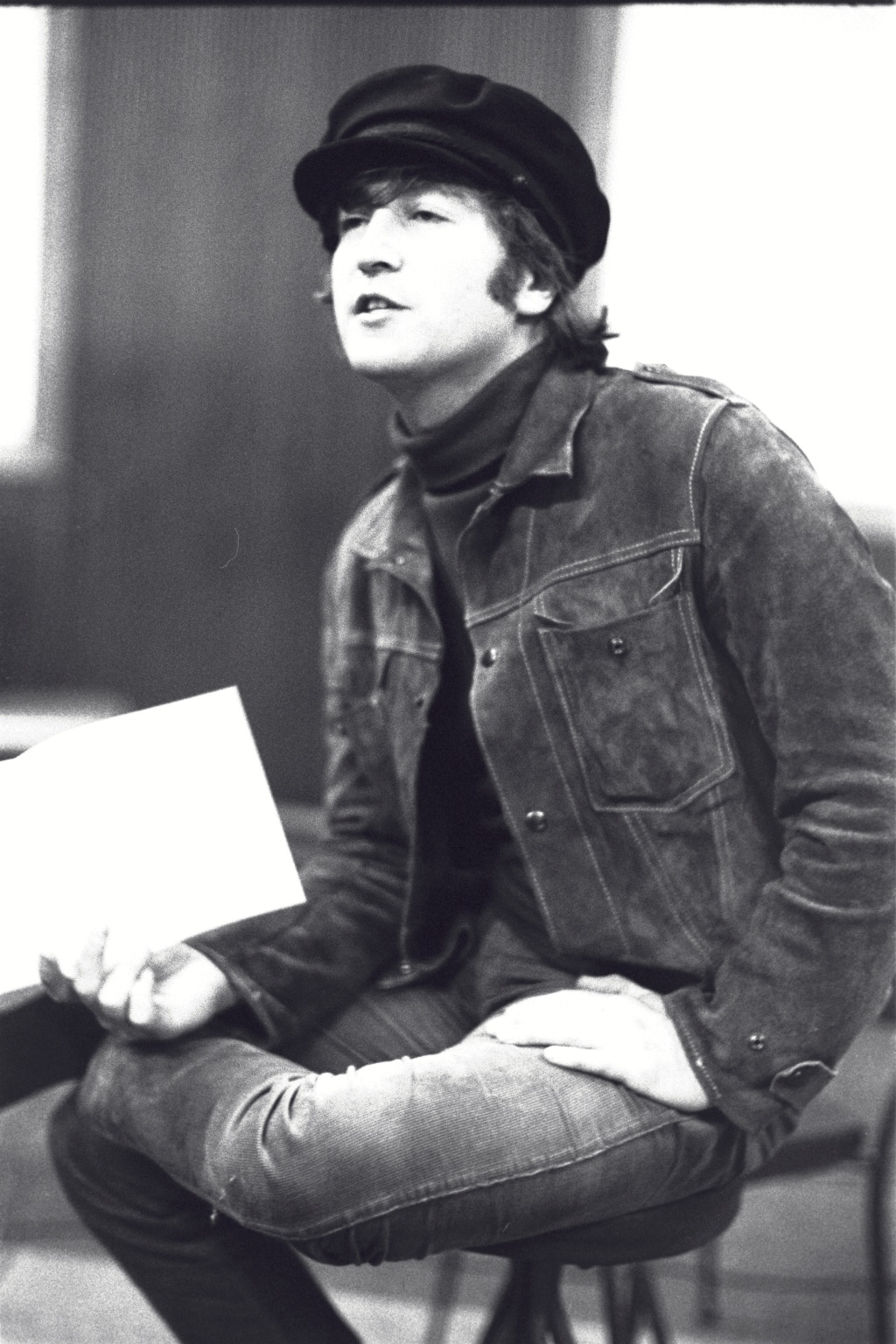

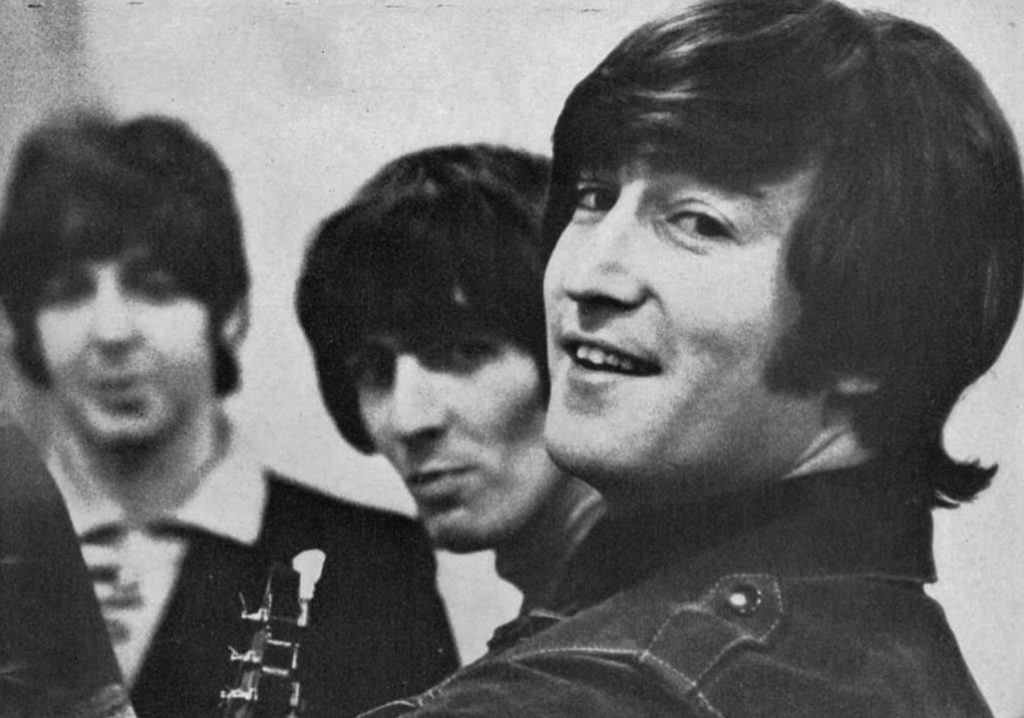

John Lennon, the lyrical composer and, he states, the musical composer (Lennon stated to David Sheff that “All Paul added to the song was the middle eight and the harmony.”) sings lead vocals and guitar on his 1961 Fender Stratocaster electric. (Hammond, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 73)

Paul McCartney, who also claims to be the musical composer, sings backing vocal and plays bass on his Rickenbacker 4001S. In his Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, Hammack points out that the Hofner 500/1 “was available, but probably unused.” (p. 73)

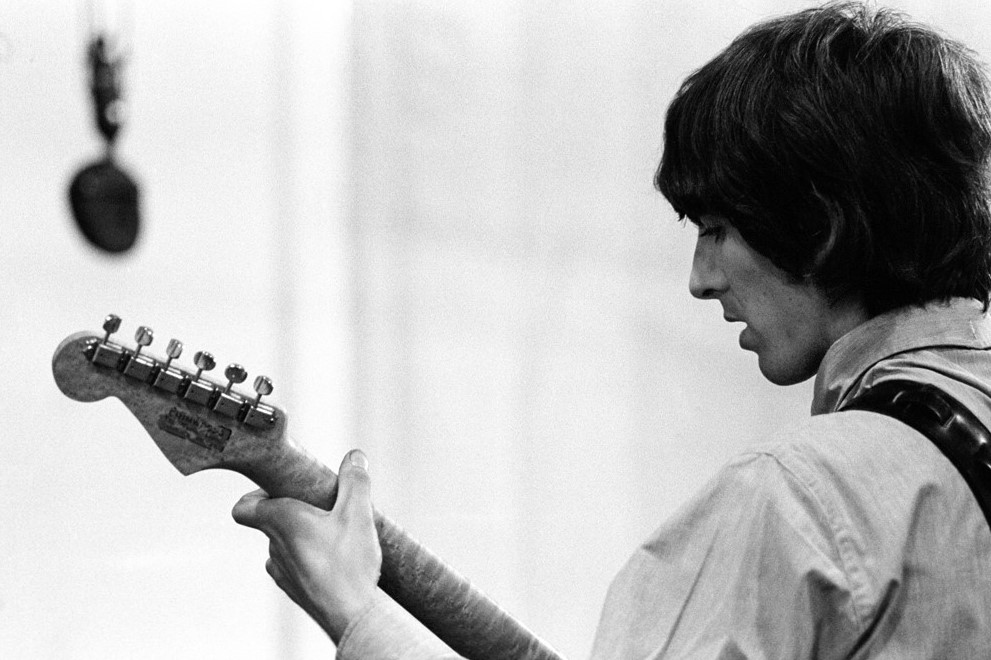

George Harrison sings backing vocals and plays lead guitar on his 1961 Fender Stratocaster electric, an exact match for John’s guitar. (Hammack, 73) Harrison plays the memorable and lovely introduction to this song. (Womack, Maximum Volume, The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, 291)

Ringo Starr plays one of his Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl Super Classic drum sets (Hammack, 73 and Womack, 291)) and tambourine.

George Martin, plays the baroque “middle eight.” The complete story of this solo is covered in the “What’s Changed” section below. (Womack, Maximum Volume, The Life of Beatles Producer, George Martin, 290-291.)

Sources: The Beatles, The Anthology, 194, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 202-203, Lewisohn, The Recording Sessions, 64-65, Womack, Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, 122-124,Womack, Maximum Volume, The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, 290-291 and 294, Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, 462-464, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 302-303, Winn, Way Beyond Compare, 365 and 367, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 73-75, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 96-98, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 203, Coleman, Lennon, 299, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and The Sixties, 136-137, Riley, Tell Me Why, 166-168, Sheff, The Playboy Interviews, 149 and 151, Norman, John Lennon: The Life, 417-418, Miles, Paul McCartney, Many Years From Now, 276-278, Babiuk, Beatles Gear, 169-170, and Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 33-34, and In My Life” by The Beatles. The in-depth story behind the songs of the Beatles. Recording History. Songwriting History. Song Structure and Style. (beatlesebooks.com)

What’s Changed:

- Overt autobiographical references set to a solemn melody –

Although many (if not most) of John’s songs prior to 1965 had been highly autobiographical, hits such as “I’ll Cry Instead,” “Tell Me Why,” and “Help!” had been accompanied by up-tempo music that made them seem happy, light-hearted, and upbeat. Even when John’s confessionals were backed by more somber music – as in the case of “If I Fell,” “I’m a Loser,” and “Not a Second Time” – the public perceived them merely as universal love songs, songs that could apply to anyone. Few guessed that rich, powerful, successful John Lennon was singing about his own wounds and fears.

“In My Life,” however, was at last quite completely candid about the joys and sorrows John had experienced. Spurred on by journalists John respected (including Maureen Cleave and Kenneth Alsop) who encouraged John to be more openly autobiographical and literary…and validated by the nature of Dylan’s popular “Freewheeling” LP, John summoned the courage to make “In My Life” an overtly personal release. He didn’t try to buoy it up with lively music or brush it off as nonsense or gobbledygook. John owned “In My Life” as “my first real major piece of work.” (Sheff, The Playboy Interviews, 151) Without excuse or camouflage, John laid bare his heart.

- Inclusion of a classical sounding (“Bach inversion”) piano solo –

John had originally envisioned a guitar solo as the instrumental solo for “In My Life.” He had even devised an intricate melody line for this part of the song. And in keeping with his wishes, a guitar solo was recorded. In his book, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Jerry Hammack states that this might have been a dual solo, recorded by Harrison and Lennon. He writes: “…the solo appears to have been played by two different guitars. Harrison recalled that on October 22nd, he and John played a dual solo on ‘Nowhere Man,’ so the dual performance is a distinct possibility.” (p. 74) However, this solo just didn’t turn out to be as poignant or effective as John wanted it to sound, and he expressed those misgivings to George Martin.

In Kenneth Womack’s, Maximum Volume, The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, we are told, “Lennon and Martin set about the business of recording a keyboard solo for ‘In My Life’…To Lennon’s mind, the solo was an essential feature – a highly melodic means of underscoring the song’s nostalgic power. With a Hammond studio organ on hand, Lennon opted for a classical sound in the manner of J.S. Bach. As The Beatles lacked the ability to score music…Martin sat beside Lennon in Studio 2. As Lennon sang the notes of a potential keyboard solo, Martin doubled the sounds on the grand piano with one hand while charting them in his notebook with the other. With the keyboard solo having been fully realized, Martin sat before the Hammond organ as Norman Smith cued up the existing first and second takes of ‘In My Life.’ But as he listened to the playback with Smith and The Beatles, Martin was decidedly underwhelmed [with the solo]…The organ sounded thin and lifeless in contrast with the song’s moving lyrics…”(p. 291)

So, the evolution of the lovely solo that John had composed did not end there. Womack goes on to say, “…on Friday, October 22…the band’s producer turned his attentions back to ‘In My Life.’ George was determined to unseat the Hammond organ solo that he had recorded…a stunning song and glorious song such as ‘In My Life’ deserved a much grander fate.”

To find out “the rest of the story” (as journalist Paul Harvey used to say), join Susan Ryan later in this blog for “A Fresh New Look” at the so-called “middle eight.”

- Highly-contested authorship and performance debates –

In the early years, The Beatles admittedly collaborated quite frequently on songs such as “She Loves You” and “From Me to You.” But as time went along and they lived further from one another, they began to write the body of a song singly, later altering that song with words or phrases deftly supplied by the other Beatles (such as John’s endorsement of “the movement you need is on your shoulder” in “Hey Jude”) or tweaking a composition here or there, with a little help from their friends. (Pete Shotton, for example, claimed to have contributed significantly to “I Am the Walrus”).

Of course, there were always some true collaborations such as “We Can Work It Out” and “A Day in the Life,” but these partnership productions were less prevalent post-1964 than they had been in the group’s ingenue years. Therefore, it was rare for a song’s authorship to be debated. “In My Life” is one of the few songs in contention. As Ken Womack points out in Long and Winding Roads, The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, “It was certainly a song over which claiming authorship was a worthy goal indeed.” (p. 124)

More on this topic as we now join Beatles author Susan Ryan for…

A Fresh New Look:

Jude Southerland Kessler was thrilled to be able to interview Susan Ryan, for this deep-dive into John Lennon’s “In My Life.” When considering Lennon’s masterpiece – a song that Philip Norman has called “a superlative achievement” (John Lennon: The Life, 417) and Ken Womack has dubbed “John Lennon’s…exquisite composition.” (Maximum Volume, 290) Ryan has conducted tours of John Lennon’s New York City for many years as part of her company, Fab Four Walking Tours, and she is featured in the DVD “John Lennon’s New York City.” Kessler commented, “It would be difficult to find anyone who would know John Lennon better than Susan Ryan!” Here is their recent conversation:

Jude Southerland Kessler: Susan, congratulations on your new book co-written with David Bedford and Richard Porter, The Beatles Fab Four Cities! I’ve read it cover-to-cover and am really impressed with the depth of research and the wealth of Beatles history in its pages. I know you’re busy promoting it on podcasts, radio programs, social media, and so forth. So, thank you for taking time out to join us for this consideration of “In My Life!”

Susan Ryan: Thanks for asking me to help with this project, Jude! Rubber Soul is pretty much my favorite Beatles album, and being able to discuss “In My Life,” a song that has been one of my favorites forever, is a true privilege. I’m also glad to hear that you are enjoying The Beatles Fab Four Cities! Working on that book with David and Richard has also been a true joy, allowing us to share our personal passions as tour guides in our individual cities with all Beatle people!

Kessler: Well, let’s jump right into the heart of this beautiful Lennon ballad, “In My Life.” Susan, Ray Coleman in Lennon has this to say about John’s work on Rubber Soul: “For Lennon, particularly, this album marked a personal progression in his craft. Personal honesty and confession, which were to characterize his later work, were inherent. His songs are marked by a more poetic approach, and he was beginning to find his own voice.” How is Coleman’s observation well-illustrated in John’s poignant Side Two creation, “In My Life”?

Ryan: Certainly, by the time Rubber Soul and “In My Life” came out, John’s songwriting was maturing at rapid rate. His lyrics had already begun to exhibit a much more personal bent, less of the “I love you; you love me; she loves you” of earlier works. “In My Life” is absolutely an intensely personal reflection, a look back on simpler days and the people and things that were near and dear to John’s heart, and much more straightforward than previous “personal” songs that were covered up by cheerful pop melodies.

It is also interesting that the song came from someone so young – normally, a listener would not expect a man of just under 25 years of age to be able to craft such a heartfelt song about “looking back,” but John manages it, and you can hear his longing for times gone by, even if those times were not so very far in his past. Given everything that The Beatles had been through up to this point, becoming virtual prisoners of their fame, it’s not surprising that he would be wishing for the way things had been before they were swallowed up by fame and fortune. It is also a definite step towards the sometimes brutal honesty that would characterize so many of John’s later songs, both with The Beatles and solo – songs like “Julia” on the White Album, where he sings about his mother, but also inserts his hope for the future with Yoko, or the songs on the John Lennon Plastic Ono Band album, nearly all of which are personal to the point of pain.

But it is with songs like “In My Life,” however, where the seeds for those songs and others begin to take root, and where his ability to craft beautiful, passionately personal songs that were destined to endure as pop standards began to emerge, although he could (and did) still write perfect bits of more commercial pop as well. It’s no wonder this song means so much to so many people – even though they are John’s memories, there’s a universality to the lyrics, set to the lovely melody, that resonates with so many people and their lives.

Kessler: John wrote a third verse for “In My Life” that specifically mentioned places in Liverpool he so vividly recalled. However, he removed this bit because he said it felt too much like a “What I Did on Summer Vacation” essay. Share that verse with us, please, and if you don’t mind, please give us your reaction to the lyrics that were omitted.

Ryan: Here’s the omitted verse:

Penny Lane is one I’m missing

Up Church Road to the clock tower

In the circle of the Abbey

I have seen some happy hours

Past the tram sheds with no trams

On the 5 bus into town

Past the Dutch and St Columbus

To the Dockers Umbrella that they pulled down.[i]

Frankly, anyone who hears this song in its final form would have to agree with John; it reads like a travelogue or a “guide to Liverpool landmarks.” If it had been left in, it would have made what is a poignant, universally accessible song into something a little too personal and specific. By omitting this verse, the song becomes something else – it takes on a life as a song any listener can relate to, no matter who they are or where they’re from. Everyone looks back at some point in their lives to “people and things that went before,” or remembers “friends and lovers….some (who) are dead and some (who) are living.” But not everyone is from Liverpool – and while the places mentioned specifically in those omitted lyrics may have meant something to John personally, or to the other Beatles or other Liverpudlians, they just would not have the same resonance to someone from New York or Los Angeles or any other place.

Removing this verse and leaving the form of the song as we know it was a brilliant move, whether originally intended or not, because even though the song remained intensely personal as far as John was concerned, it allowed other people to hear it and put themselves in the situation – the best way to create a “standard.” There’s a reason this song is sung at weddings and funerals and other life-cycle events – it means something to everyone precisely because it is not time- or place-specific.

Kessler: Susan, John admitted that several influences led him to write this very autobiographical song in 1965. Tell us about those people who encouraged him to be more introspective.

Ryan: Prior to this song, although John had definitely written songs that were personal, he’d hidden that behind catchy pop melodies or found other ways to disguise the fact. By the time he was working on this song, however, he’d done a couple of interviews with people who had asked him outright why he didn’t write more sophisticated, introspective songs. One of these was Maureen Cleve of the Evening Standard, who quite literally asked him why he “didn’t ever write songs with more than one syllable?” A second journalist, Kenneth Allsop, asked him why his songs didn’t contain the same kind of depth and meaning that his poetry and prose did when interviewing him after the publication of In His Own Write. All of this led John to begin thinking about doing something more serious and personal.

Add to this the release of Bob Dylan’s seminal work, “Freewheeling,” which was full of autobiographical songs, and John realized that if he wanted to do something more serious, he had to take that leap and be willing to share things of a more personal nature in his work. For a man who most often carried his most intense personal feelings close to the vest, it was a huge step into the unknown, but as I mentioned above, it was also the seed that grew into so many other personal, autobiographical, confessional songs later in his life. The beautiful, tender melody also brought out a softer side of the man who had previously been perceived by many as the “rocker” of the group.

Kessler: All right, let’s address the elephant in the room. John was very proud of “In My Life.” In fact, he said it was “his first real major piece of work.” John emphatically said that Paul didn’t even see the song until the lyrics were finished and that “[Paul’s] contribution melodically was the harmony and the middle eight.” Paul, just as insistently, claims to have written the melody. This is the short version of this disagreement. Give us the details, please.

Ryan: Wow, Jude, you really want to open a can of worms here, don’t you?

There are numerous interviews where John states that he wrote the lyrics to the song first and the music later. This was frequently how he wrote – he’d start with an idea and then come up with the music. In the group’s early years, both John and Paul emphasized their “collaborative” songwriting, stressing the idea that every song they created was a totally collective endeavor by “Lennon and McCartney.”

However, in later years, both of their recollections about who wrote the actual melody began to diverge. In a 1980 interview, John said, “There was a period when I thought I didn’t write melodies; that Paul wrote those and I just wrote straight, shouting rock ‘n’ roll. But of course, when I think of some of my own songs – “In My Life” or some of the early stuff….I was writing melody with the best of them.”[ii] In that same interview, he stated unequivocally that “Paul helped with the middle eight.” But there was controversy as early as 1976-77 – when Paul was shown a list of Lennon-claimed songs by Hit Parader Magazine, the only one he disputed was “In My Life,” claiming that he’d written the whole melody from beginning to end, inspired by Smokey Robinson.

This claim to the authorship of the melody continued when Paul reiterated his statement in 1998, in Barry Miles’ biography of him, Many Years From Now, disputing previous statements by John insisting that his contributions to the song were minor. The fact that John died in 1980 and isn’t here to clarify these claims certainly makes it difficult to discern who was the real author of the music, but given that the song is so intensely personal, it seems logical that John wrote the majority of the song, with only small contributions from Paul in sections such as the middle eight/bridge.

Another fascinating thing is that the handwritten lyric sheet of the completed song, which is in John’s handwriting, has only one credit at the bottom – John Lennon! When songs were more collaborative, they’d sign them with both their names.

I did find an interesting tidbit that said that in 2018, Harvard University applied an artificial intelligence model to the music of the song, and determined, by their calculations, that there was a “.018% possibility of McCartney having written the whole of the music.” They gave John an 81.1% certainty of having written the verses, and Paul a 43.6% certainty of writing the middle eight, which means that although the song did contain some obvious collaboration, the vast majority of it was written by John. I’m inclined to agree.

Kessler: As Ian MacDonald points out, there really is no bridge in this song. However, there is an instrumental bridge, artfully created by George Martin. It wasn’t the first bridge composed for the song, however. Please tell us about both bridges and how, by strange coincidence, they “come together.”

Ryan: As Jude mentioned earlier in the “What’s New” segment of this blog, “In My Life” doesn’t really have a “middle eight” as people who are familiar with the songs of Lennon and McCartney would recognize. Instead, it has an instrumental bridge, played by George Martin on what is credited on the album cover as a harpsichord. More on that later…

The song was recorded on October 18, 1965, during what was a relatively short studio session for The Beatles. By the end of the day, they had completed most of the song, but there was a section in the middle that was left out because John couldn’t decide what to put there. Originally it was a guitar piece by George Harrison, but that didn’t hit the right note. George Martin left a gap in the song and John suggested that he supply one himself. In a 1970 interview, John stated, “In ‘In My Life’ there’s an Elizabethan piano solo. We’d do things like that. We’d say, ‘play it like Bach,” or ‘could you put twelve bars in there?’”

With that rather vague instruction, George Martin was left to his own devices to create something to place into that section of the song. He worked on the section four days later, on October 22, 1965, when he wrote and recorded something he described as being “like a Bach inversion.” He recorded it first on a Hammond organ, but then did it again on the piano because he didn’t like the sound of the organ. It’s here where George Martin’s genius really shows through, because he used a technique called the “wind-up piano,” with the solo recorded at half speed and an octave lower. When played at normal speed, this made the piano sound like a harpsichord – an auditory trick that no one even realized at the time! When he played it back for the Beatles when they came back to the studio, they loved it, and left the “harpsichord” solo that we all know and love as part of the song.

Kessler: Susan, amazing work! I’ve so enjoyed this. Thank you for taking time out of your preparations for the New Jersey Fest coming up on April 1-3 to be with us this month for the Fest Blog!

Ryan: Thanks again for this opportunity, Jude! It’s been a true pleasure! I’m looking forward to hearing what people think about our discussion of this special song, and to seeing folks at the New Jersey Fest in April!

For more information on Susan Ryan and The Beatles Fab Four Cities:

The Beatles Fab Four Cities by Ryan, Bedford, and Porter had been acclaimed as “a must for every Beatles fan” by Billy J. Kramer. To find out more about the book, HEAD HERE

To purchase The Beatles Fab Four Cities, HEAD HERE

To hear Susan Ryan, David Bedford and Richard Porter discuss The Beatles Fab Four Cities on the “She Said She Said” podcast, HEAD HERE

To discover more about Ryan’s Beatles Tours of New York City, HEAD HERE

To follow Susan Ryan on social media, HEAD HERE

[i] The original lyrics to “In My Life” may be viewed here

[ii] Sheff, David, The Playboy Interviews with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, p. 116-117