Author: Danny

Revolver Deep Dive Part 9: And Your Bird Can Sing

Side Two, Track Two

In Which “You Don’t Get Me” becomes “And Your Bird Can Sing”

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Erin Torkleson Weber

This month, our Fest Blog continues our in-depth study of Revolver with a song that has “more than meets the eye.” It’s John Lennon’s enigmatic “And Your Bird Can Sing,” a track full of vitriolic lyrics, incredible musicianship, and controversy about “who did what.”

Joining Jude Southerland Kessler, author of The John Lennon Series this month to explore this song is the highly respected author Erin Torkelson Weber. A graduate of Newman University and Wichita State, after completing her graduate degree, Erin Weber began teaching American History part time at Newman University. Looking for a new, more modern subject to appeal to students in her senior seminar and research classes, Erin, a Beatles fan since childhood, began researching the band’s historiography. In 2016 McFarland published her work The Beatles and the Historians: An Analysis of Writings About the Fab Four, which examines the historical methodology and historiographical arc of the Beatles story. In addition, Erin helps run a blog, “The Historian and the Beatles,” which provides book reviews and source analysis of various Beatles works: she also co-hosts “All Together Now,” a podcast with Karen Hooper, and has guest starred on numerous other podcasts. Erin is a beloved member of our Fest Family, and we welcome her to the blog!

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 20 April 1966

Time recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 2.30 a.m. (Note: Lewisohn points out that also recorded on this long day in studio were 4 rhythm track takes of “Taxman.”)

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil MacDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 75)

On this day: A backing track was created with Ringo on his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set and George on his 1965 Rickenbacker 360 12-string electric. There is a second guitarist, and the identity of that person has been questioned and debated through the years. In The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, Hammack states that it was “either Lennon on his 1961 Fender Stratocaster with synchronized tremolo or McCartney on his Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino electric guitar with Selmer Bigsby B7 vibrato.” (p. 125) Hammack notes that when George Harrison was quizzed about who performed on the second guitar by Guitar Player magazine in 1987, Harrison admitted that he didn’t know the answer. Hammack says that he feels “Lennon’s aggressive count-in indicates him as the guitarist,” but there is no conclusive proof. On this same track, John and Paul also sang on the backing vocals. (Hammack, 125)

Two takes were performed. Take Two was deemed “best.”

Then, superimpositions followed:

McCartney performed on his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass

Harrison performed a guitar solo on one of 3 guitars he had in studio

Starr performed on tambourine

Paul and John double-tracked the backing vocals. The harmonies in the backing vocals are quite intricate and of note. This often-overlooked song has many layers.

Date Reworked: 26 April 1966

Location for both sessions: EMI, Studio Two

Time recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 2.45 a.m.

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 76)

On this day: The Beatles decide to completely remake “And Your Bird Can Sing.” In 11 takes, (which are numbered 3-13) The Beatles create a completely new backing track. Hammack tells us that “Lennon [is] either on his Fender Stratocaster or his Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino electric guitar, Harrison [is] again on [his] Rickenbacker 360-12 electric guitar, McCartney [is] on his Rickenbacker 4001S bass, and Starr is on his Ludwig drums. (Hammack, 126)

Takes 6 and 10 were selected as “best.” Superimpositions included:

Ringo on tambourine

Ringo on high-hat and cymbals

Eventually, Take 10 would be chosen as “best,” but Paul’s bass work on Take 6 would still be dubbed as the best. So, these elements were blended.

Once again, the harmony lead guitar work is questioned. There is no doubt that Harrison performed. But no one knows for sure if Lennon or McCartney accompanied him.

As the last order of business, Hammack tells us, “Finally, John added his lead vocals with McCartney and Harrison on backing vocals and hand claps (all recorded with frequency control (varispeed) at slower than normal tape speed, on playback sounding around half a semitone higher in pitch.)” (The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, p. 127)

***See Jerry Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 125-128 for more information.

Other Valuable Sources: Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 75 and 77 , Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 218 and 219, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 12-13 and 14-15,Lennon, Cynthia, A Twist of Lennon, 128, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 89 and 123-126, Robertson, The Art and Music of John Lennon, 54-55, Gould, 360, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 215, Spizer, The Beatles Rubber Soul to Revolver, 219, Turner, Beatles ’66, 159-161, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 111-112, Margotin and Guesdon, 340-341, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 169-171, Spignesi and Lewis, 79-80, Riley, Tell Me Why, 192-193, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 159, Womack, Long and Winding Roads (2007 edition), 143-144, Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia, 36-37, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 125-128, and Mellers, Twilight of the Gods, 76.

A Fresh New Look:

Jude Southerland Kessler: Erin, the recording of “And Your Bird Can Sing” took two long days of studio work – 13 takes! Yet, in The Beatles Anthology, John Lennon categorizes “And Your Bird Can Sing” as “one of my throwaways.” This is a typical Lennon “tell,” a phrase he consistently uses to characterize songs that reveal too much emotion, leaving him vulnerable. John applies the epithet to 1965’s “It’s Only Love,” which explores the deepening rift in his relationship with Cynthia. He applies it to “Run for Your Life,” a song that lays bare his jealously and feelings of inadequacy. (He told David Sheff that only after his Primal Scream therapy was he able to write a song openly about these feelings: “Jealous Guy.”) Is it possible that John is rebuffing other deep-seated emotions in this song as well?

Erin Torkleson Weber: A “throwaway” song would presumably come across as (by Beatles standards, anyway) formulaic and relatively unremarkable, and “And Your Bird Can Sing” is neither. John’s ex post facto dismissal of its significance (he criticized it several times after the band’s breakup, both in 1971 and 1980) doesn’t erode the song’s lyrical bite and sharp edges, which appear to offer a glimpse into John wanting, for lack of a better term, “top billing” from someone with whom he’s connected, and whose preoccupation with tangential things is apparently mucking up their connection with and understanding of the singer, John. Given what we know of John’s deep-seated, lifelong fear of abandonment, this reading of the song would make it the furthest thing from a throwaway; rather, it can be seen as an expression of insecurity and frustration at an important someone’s not prioritizing him and letting him down by not “getting” him. One of the authors to underscore this song’s possible emotional significance is Tim Riley, who notes “the implied rejection” (Riley, Tell Me Why, 192) evidenced by the snag in Lennon’s vocalization of “me.”

However, Riley appears to be one of the authorial exceptions. In his excellent work, Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America, Jonathan Gould describes “And Your Bird Can Sing” as “directed at an anonymous adversary,” (Gould, 359), and that adversarial component is what has drawn the most focus and encouraged significant speculation over the decades, by numerous authors, over whom John is addressing. Theories have ranged from Mick Jagger to Frank Sinatra, usually arguing that the song was provoked by Lennon’s “professional jealousy” (Gould, 360) and/or his dismissal of individuals whose pretension blinded them to true enlightenment. (Turner, Beatles’ 66: The Revolutionary Year, 160).

Yet these interpretations tend to ignore that, at the same time it criticizes, “And Your Bird Can Sing” also attempts to offer its subject some reassurance. “I’ll be round,” is, after all, wrapped inside the warning “you don’t get me;” a very appropriate lyrical pivot for the emotionally mercurial Lennon. This appears to indicate that, once the subject has tired of their pretentious distractions, Lennon and the song’s subject can possibly “see” one another and connect.

This reading of the song would certainly seem to eliminate Gould’s speculation that it was directed at Sinatra, to whom John would hardly be inclined to want to “see” or “get” him. And Faithfull’s speculation that the song was directed at Jagger (identifying her, Marianne, as the “bird” in the song) is purely that, speculation. (Rodriguez, Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 89). This overall reading of the song inevitably leads us to the question: Whom did Lennon feel, during this point in the Revolver sessions, wasn’t understanding him or prioritizing him the way he needed? That’s a level of lyrical analysis that’s above my historian’s paygrade, but a fascinating question to ask, particularly given John’s latter strong dismissal of the song.

Kessler: Erin, as a follow-up question… In the wake of his successful volumes, In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works, John had contracted with Jonathan Cape Publishers to write a third book to be released in February 1966. And writing was important to John. Indeed, when asked by Kenneth Allsop which profession he would prefer if he could choose between writing songs or writing books, John immediately chose writing books. He told Allsop he’d been doing that long before he became a Beatle. However, by the end of 1965, John admitted that he had only one poem prepared for the upcoming book, and so, he abandoned the idea of publishing again. Of course, John’s unrelenting schedule in 1965 must have had a great deal to do with that decision. But, do you think it’s possible that songs such as “And Your Bird Can Sing” gradually supplanted John’s need to write emotional, soul-revealing poetry and prose?

Weber: This is an excellent question, because it offers a chance to delve into issues regarding John’s creative process, and how that process was impacted by external and internal factors. What’s interesting about John’s schedule in 1965 is that you can make the argument his earlier schedules from the years when he wrote In His Own Write, published in 1964, and A Spaniard in the Works, which was published in June of 1965, were equally frantic. Why would this demanding schedule only begin to slow down his literary productivity by the end of 1965, when it hadn’t seriously impacted it before? Having said that, you can certainly argue that it was the cumulative effect of what had been, at that point, approximately three years of an unrelenting schedule, frantic pace, and constant demands of new songwriting material that played a role in preventing John from producing his third book.

We can speculate on any number of reasons, in addition to his frantic schedule, as to why John ultimately didn’t produce his third book. John told Allsop that he preferred writing books to writing songs, but the reality is that contractual and studio demands unquestioningly and unrelentingly prioritized song writing. So did the band’s group ethos and his competitive partnership with Paul.

Additionally, the argument that John’s realization that he could use song lyrics, such as those in “And Your Bird Can Sing,” to express the emotions previously and primarily expressed in his poems, letters and cartoons is a convincing one. In The Art and Music of John Lennon, John Robertson notes how Lennon’s “prose and verse writing had once been a form of exorcism,” (Robertson, 50) but argues that the lyrical example of Bob Dylan, coupled with the sonic possibilities in the studio, essentially allowed John to exorcise these elements through songwriting in a way that he had never previously considered or been able to accomplish.

Finally, we have to note that this use of self-revealing lyrics, replacing the old outlets of poetry and prose, corresponded with John’s initial exposure to and use of LSD. Robertson discusses how Lennon’s LSD use seriously influenced his writing and also argues that, in contrast to “the more fixed medium of prose,” songwriting allowed Lennon to express “these vague, shifting feelings” created by the aforementioned LSD use. (Robertson, 50)

Kessler: To conclude, what’s your reaction to this song, Erin? Does it speak to you in any way? Musically? Lyrically? Emotionally?

Weber: For me, “And Your bird Can Sing” is an excellent case study of how our connections and reactions to songs can shift with time and experience. As a bookish, four-eyed, awkward pre-teen with only a few (but amazing, essential, now lifelong) friends, every time I heard “And Your Bird Can Sing” on my dad’s Beatles tapes, I heard it as an indictment of the “cool” crowd in my middle school: fellow preteens so obsessed with wearing the right pair of brand-name sneakers that anyone, no matter how smart or funny or warm or generous, who didn’t meet their superficial standards was shunned or teased: “You say you’ve seen the seven wonders…but you don’t see me.” It went both ways, too: in my mind, if you were the sort of individual who cared so much about such trivial, adolescent status symbols that you couldn’t bother to look beneath the surface in order to know the person underneath, I didn’t want to waste my time attempting to get to know you, either.

Decades later, and (thankfully) well removed from middle school, I have a deep appreciation for the song’s lack of sentimentality. “And Your Bird Can Sing” is a song about attempting, and failing, to connect with someone. This is a feeling to which almost everyone can relate. Yet there’s no self-pity in it, and no sentimentality. I’m not a musician, or a musicologist, but my interpretation is that every other musical aspect of the song – the strident guitars, the edge in John’s voice – serves the song well. Its blend of warning over how prioritizing the wrong things – “prized possessions” – has damaged a point of connection between two people, combined with the singer’s frustration at feeling unseen and unheard, makes it relatable. Connections between people can and do fray, and while they can be patched, this song lays bare how it feels when that distance starts to occur.

What’s Changed:

Generally, this segment of the Fest blog precedes the “Fresh, New Look” interview. However, Erin Weber’s responses were so integral to the information in the following section that for this month, we’ve shifted things around. The aspect of “And Your Bird Can Sing” that has changed most over the years is the presumed identity of the protagonist, the “you” in this song. There have been many theories and suggestions proffered. Based on 37 years of study of John’s life and personality, I’m postulating yet another theory. Fifty-nine years after the song’s composition, however, no one can conclusively prove John’s intent. – Jude

As historian Erin Torkleson Weber so adeptly pointed out, Beatles experts and biographers have, over the years, offered myriad suggestions about the identity of the person to whom this song addressed. Others have claimed that they were the subjects of the song, although they can’t explain why Lennon was so annoyed with them. Marianne Faithfull, for example – as Erin indicates – swore the song was about her, claiming John’s jealousy toward Mick Jagger and herself. But Faithfull’s claim falls flat when we discover that 1) John genuinely liked Mick Jagger and 2) John wrote this song before Marianne and Mick were even “an item.”

Cynthia Lennon, who once gave John the gift of a wind-up songbird, thought the song was directed at her and said so in her first book, A Twist of Lennon (p. 128). But when we closely examine the lyrics, Cynthia meets none of the criteria to be the song’s protagonist. Cynthia had only traveled a limited number of times and all of those excursions were taken with her husband: to Ireland, Paris, Tahiti, and America for The Beatles’ Feb. 1964 visit. (Her visit to India was yet to transpire.) Cynthia had never visited exotic locations or seen “Seven Wonders.” Additionally, she knew very little about sound and music, and most crucially, she certainly didn’t have everything she wanted. John’s lyrics simply don’t fit Cynthia’s profile.

Lately, a YouTube video from James Hargreaves (which is well-presented) offers up Frank Sinatra as the song’s possible protagonist because Sinatra edged out The Beatles for The Grammy’s “Album of the Year” award in 1965 with the LP, September of My Life – and because Sinatra intensely disliked The Beatles and said so.

However, John and Paul had never “given a whit” for gold records, titles, or honors. By the summer of 1965, John had quit attending the Ivor Novello Awards. All of The Beatles complained about appearing at innumerable gold record ceremonies. In fact, in August of 1965, when compelled to attend the celebratory cocktail party given for them by Capitol Records president, Alan Livingston, George flatly refused to attend; Paul left early, and John departed not long after Paul. Such laudatory proceedings had become tedious.

All The Beatles really wanted to do was make great music. And as they returned to EMI in October of 1965 to create what would become Rubber Soul, they were inspired (and not threatened) by American competitors such as The Lovin’ Spoonful and the Byrds. In fact, the more talented their competitors (The Stones, the Byrds, the Beach Boys), the more The Beatles respected and liked them!

Frank Sinatra hardly registered on The Beatles’ radar. If the performer didn’t appreciate their hair or their style or even their personalities…well, who cared? Yet the tone of “And Your Bird Can Sing” is anything but milquetoast. It is angry. Very angry. John Lennon is singing to someone who really matters to him. Indeed, it appears that John is speaking directly to someone he knows – someone close to him whom he feels has betrayed his trust. We know this is the case because, as Erin pointed out, John vows in the bridge that no matter how cruel the person is to him,

“Look in my direction,

I’ll be ’round; I’ll be ’round.”

In other words, John has no intention of turning his back on the offender. Despite perceived disloyalty demonstrated by his former friend, John promises that he will always be there.

So, who is the protagonist of this song? John supplies numerous (though cryptic) clues to the betrayer’s identity:

- The person has “everything he wants.” (The protagonist is well-to-do: living in a chic locale and driving a prized car, making headlines and rubbing shoulders with the rich and famous, succeeding in a powerful career.)

- The person has “seen Seven Wonders.” ( In other words, the individual is well-traveled: having seen the world from the Spanish Riviera to the width and breadth of North America to exotic Hong Kong, New Zealand, and Australia. In John’s eyes, this person has seen it all, done it all. The protagonist is far more cosmopolitan than John, more polished and experienced.)

- The person purports to “have heard every sound there is.” (This tidbit clues us into the fact that the individual in question is, quite possibly, part of the music industry. However, John’s legendary sarcasm here hangs on two words: “you say.” John is smirking as he hisses, “You say you’re a music expert. You say you’ve heard every sound there is.” We get the feeling that the individual to whom John is singing has made unwelcome suggestions to John about his own compositions or performances.)

- The person has quirky, idiomatic tastes. (Well, after all, his bird is green…which leads us to perceive him as exotic and singular for his day.)

- Finally (and most significantly), this individual is extremely important to John. In fact, according to the lyrics, at an earlier point in their relationship, John wrongly assumed this person, “got him,” “understood him,” “heard him,” and “saw him.” Now, in the sunless backlash born of faithlessness, John is striking out with a lacerating verbal attack.

Who fits this five-point profile?

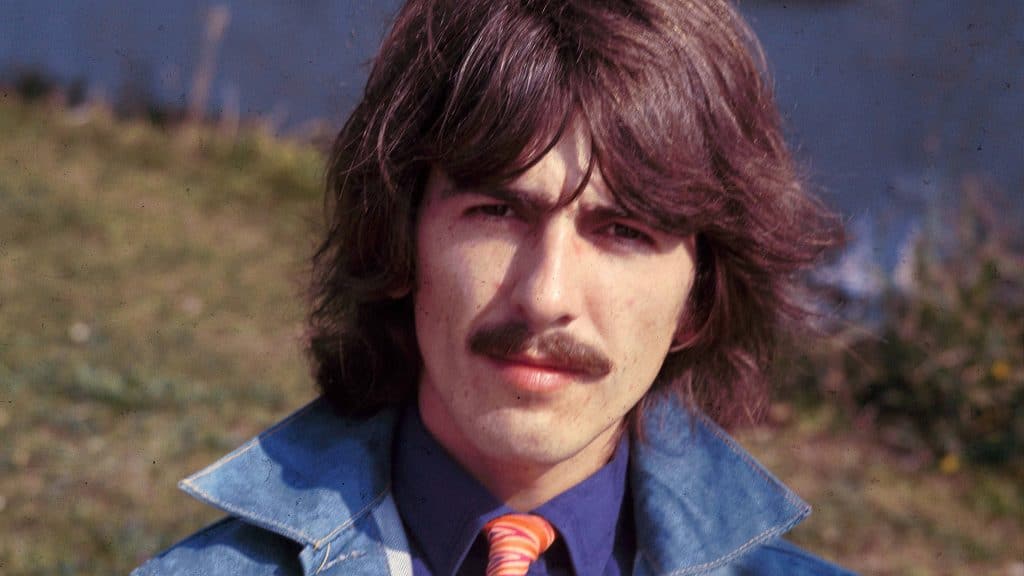

Who had a very intimate relationship with John – so deep that he shared John’s secrets and trusted John with his own? Who had been so close to John that it was rumored by mutual associates such as Yankel Feather and Joe Flannery that a possible love affair might exist between the two? Who had been John’s advocate before possessions, world travels, the myriad demands of business, and the intricate web of power struggles set in? If your answer is “Brian Epstein,” then we’re on the same page.

It is the reference to the “green bird” that really highlights Brian’s identity for us. In Liverpool’s Scouse lingo, a “baird” is a term for a girl or a girlfriend. And “to swing,” in the 1960s, meant “to step out from the norm sexually.” Thus, John’s reference to his friend’s unusual “green bird” – a bird who “swings” – was, in all likelihood, a bitter Lennonistic dig at Brian’s gay relationships. Indeed, on The Anthology version of this song, when Paul and John sing, “and your bird can swing,” they snicker naughtily at their sly double entendre.

If we agree that John is, in fact, addressing Brian in this song, a second question immediately arises: What would have caused John to become angry enough with Brian that he penned this attack – a song only slightly less hostile than “How Do You Sleep?”

By 1966, John ached to stop touring. All of The Beatles did. And although they had expressed that sentiment to Brian over and over again, he completely ignored them. While this was frustrating for Paul and George, it seemed a personal wound for John.

In December of 1961 – upon assuming management of The Beatles – Brian had pledged to Mimi Smith that no matter what happened to the other boys, he would always protect John. He had vowed to work tirelessly to defend her nephew’s best interests. But now, John feels that Brian has stopped putting him first. Consumed with what John has decided is a desire for wealth, fame, and power, Brian (John thinks) is pushing The Beatles too hard – callously demanding new films, tours, singles and LPs, interviews, radio shows, television programmes, and personal appearances. And once upon a time, Brian had promised better.

Hence, John lashes out with real invective, linking each verse with the string of repeating accusations. “You don’t hear me!” “You don’t see me!” “You don’t get me!” John sees Brian’s refusal to address his needs as a broken vow, an infidelity.

This song, therefore, fits snugly into the “broken relationships” theme of Revolver. Originally entitled, “You Don’t Get Me!” this song shatters the giddy mood of “Good Day Sunshine.” Track Two of Side One gave us “Eleanor Rigby.” Here comparably, in Track Two of Side Two, John and Brian are “the lonely people,” standing in a church of abandoned promises, surrounded by memories from May of 1963, when they vacationed together for 10 days on the Spanish Riviera or September 1963 when they spent happy days alone together in Paris. During those times, John and Brian had formed a bond born of shared vulnerabilities rarely voiced to anyone else. They had reached out to one another in mutual trust. Now, a mere three years later, John is spewing fury over the perceived perversion of that trust as Brian steadily continues to insist upon the course he feels The Beatles must follow.

For the wounded John Lennon, having “everything you want,” “seeing Seven Wonders,” “knowing every sound there is,” and even owning an exotic green, swinging bird means nothing if, in the process of garnering such success, you sacrifice friendship. Frustrated and fuming, but promising to “be ’round” when Brian finally hears him, sees him, and gets him once again, John is hanging on. However, the unresolved chord at the end of this song reminds us that in the future, anything can happen.

Sadly, by August of 1967, anything did happen. Fame exacted its price. And the birdsong fell silent.

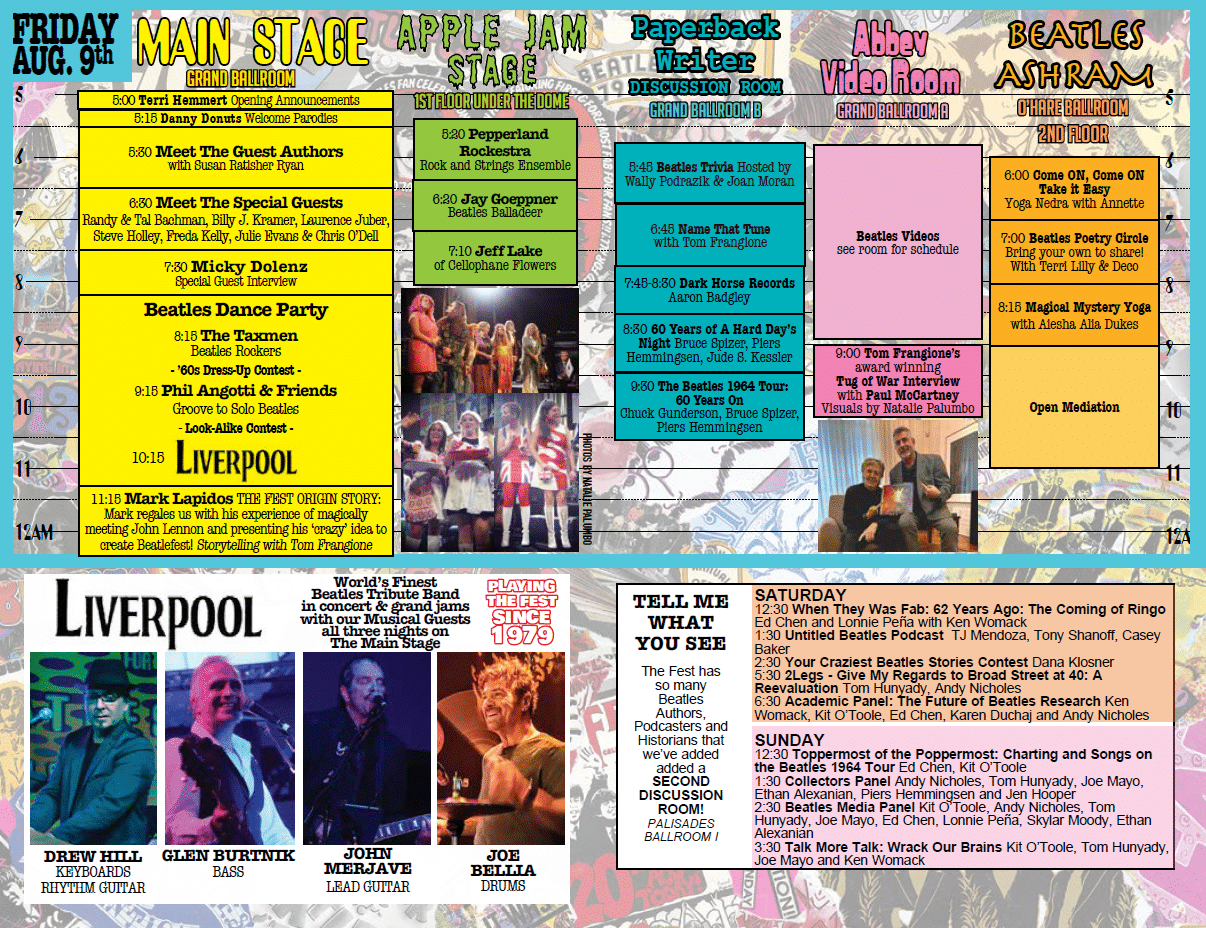

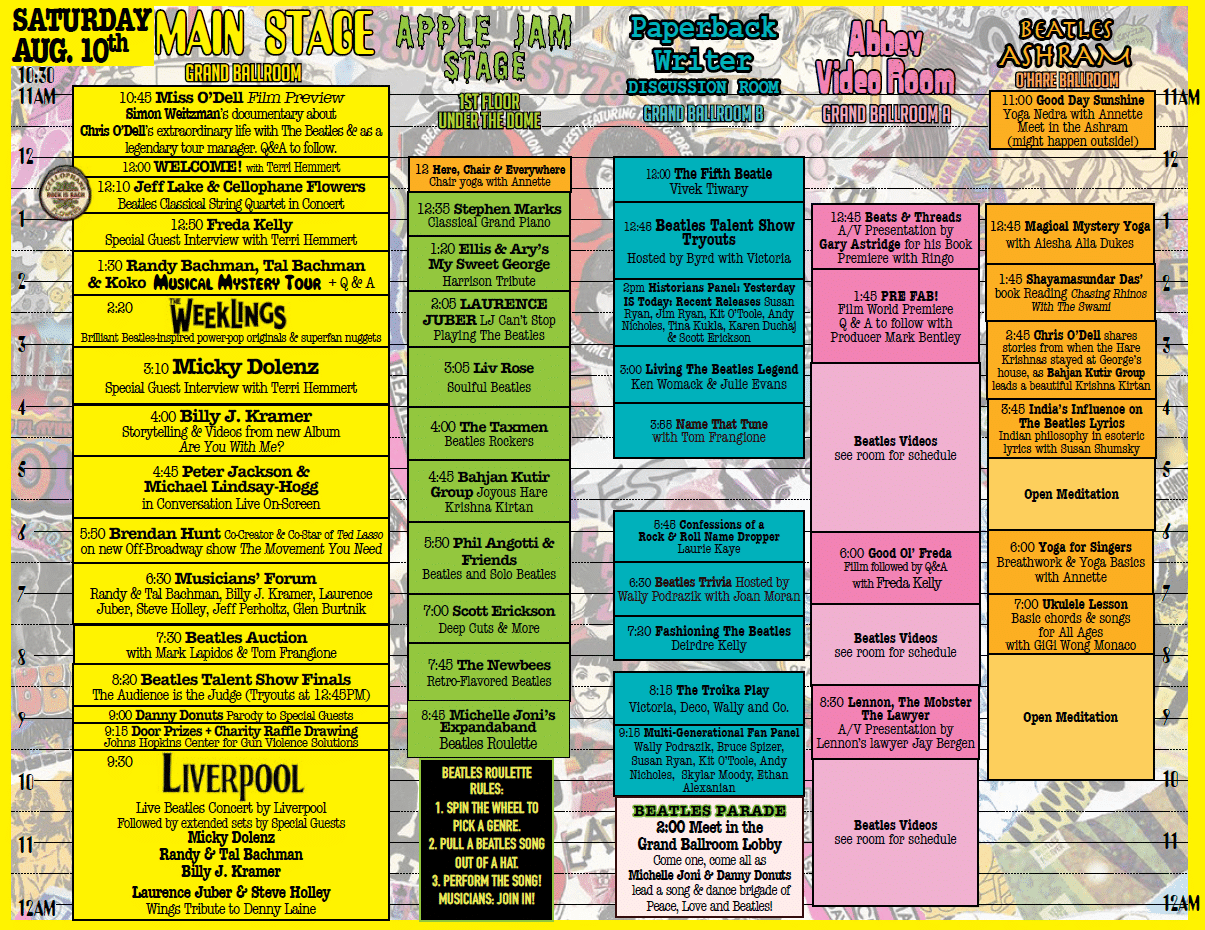

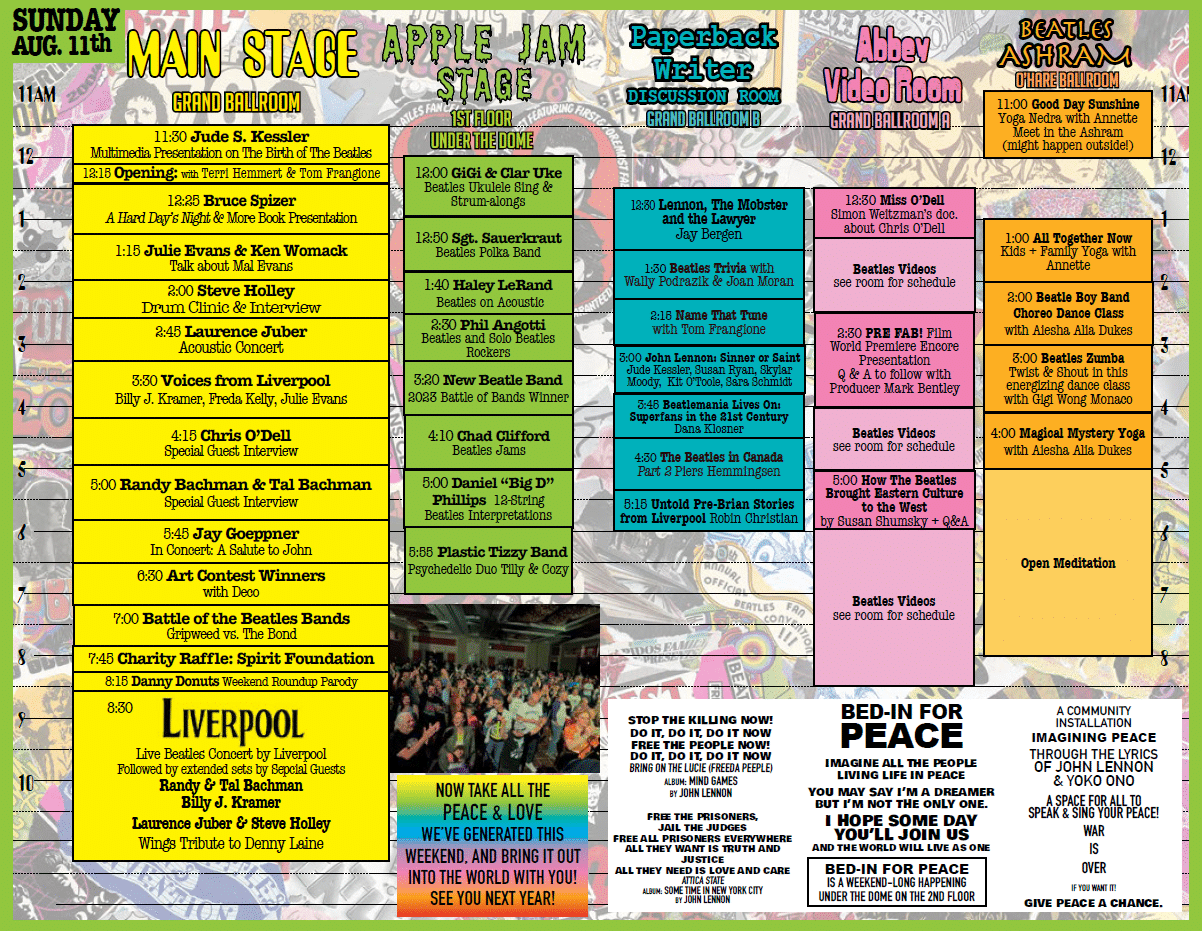

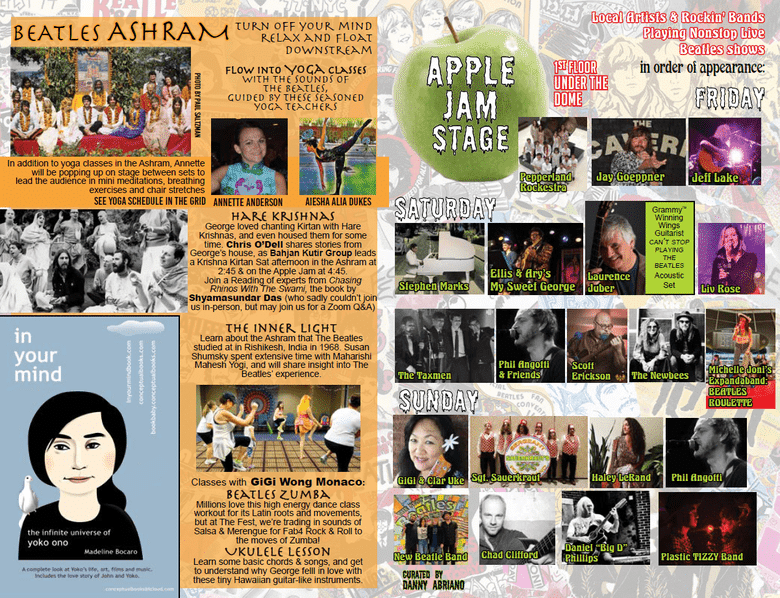

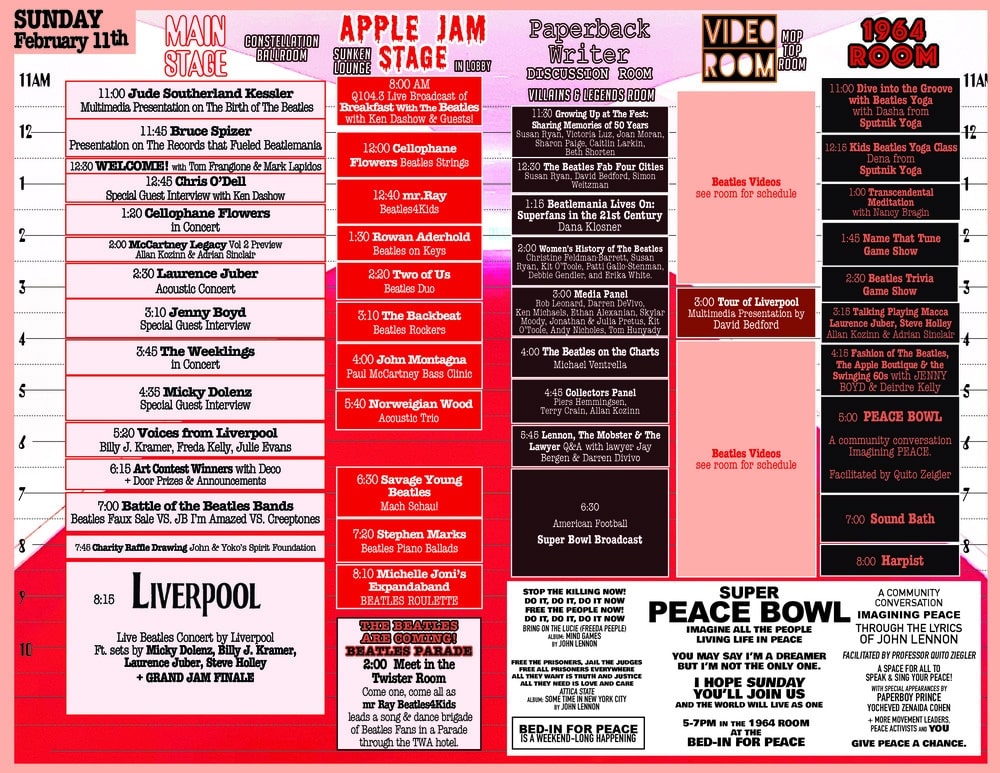

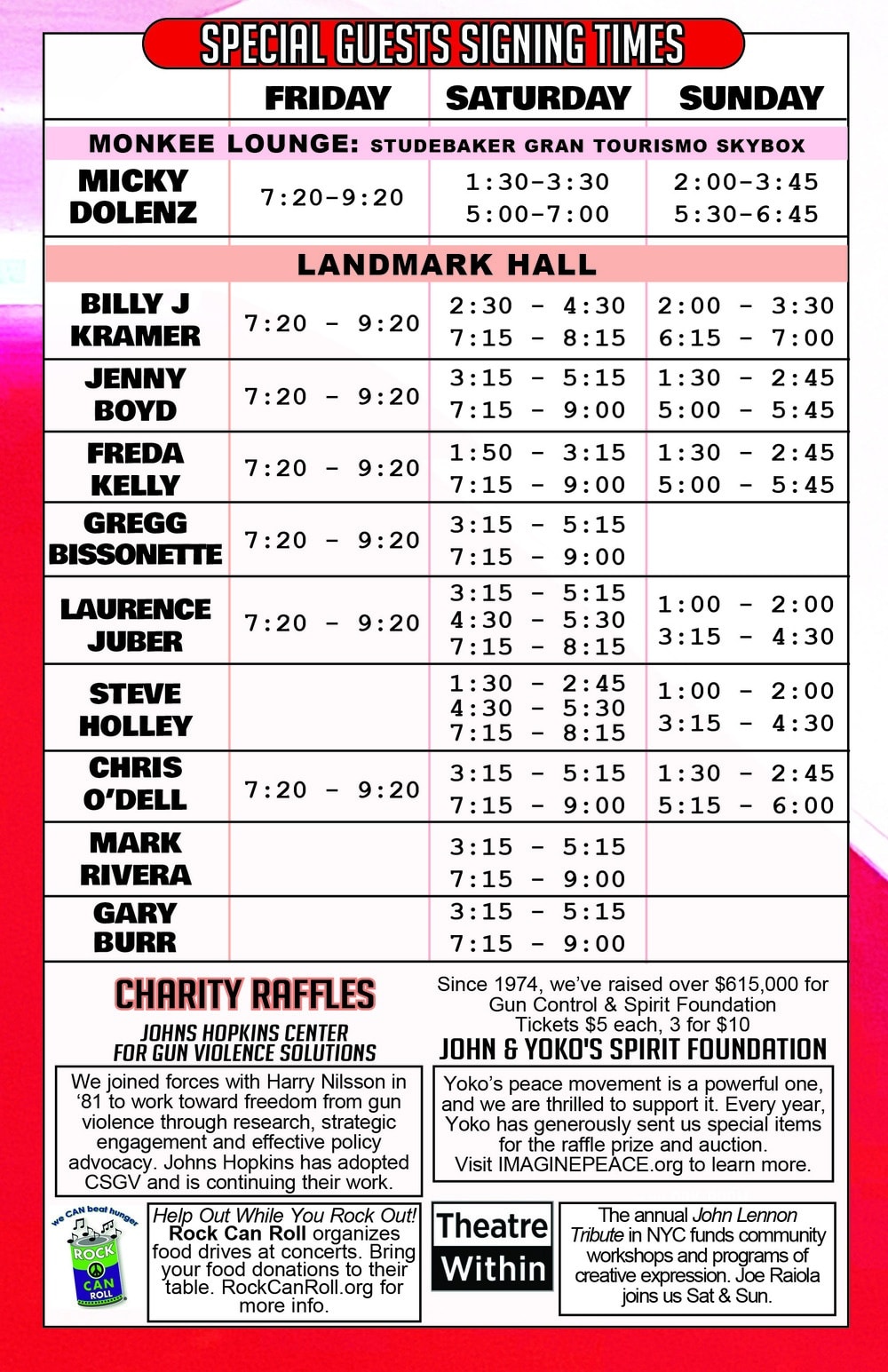

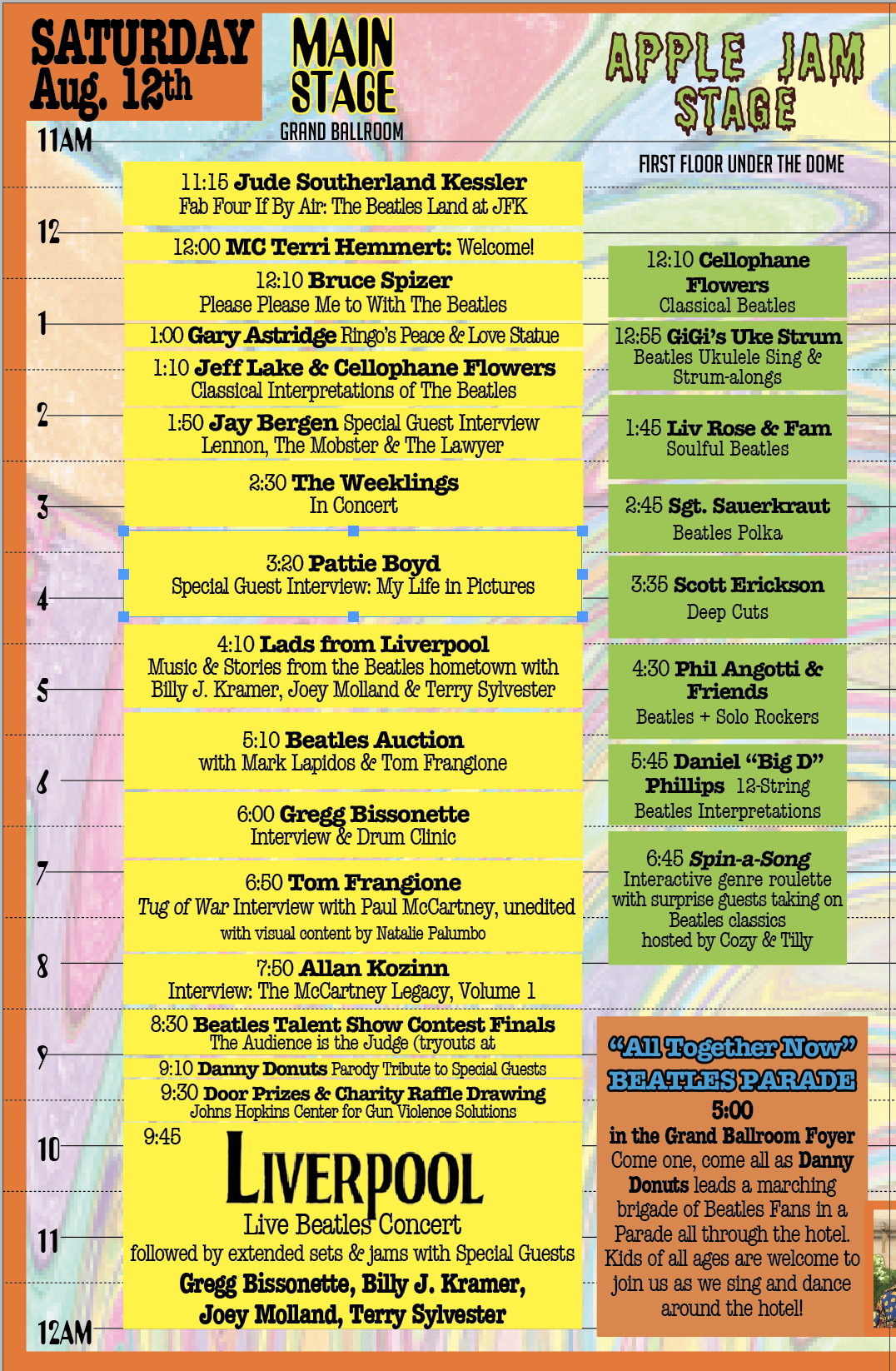

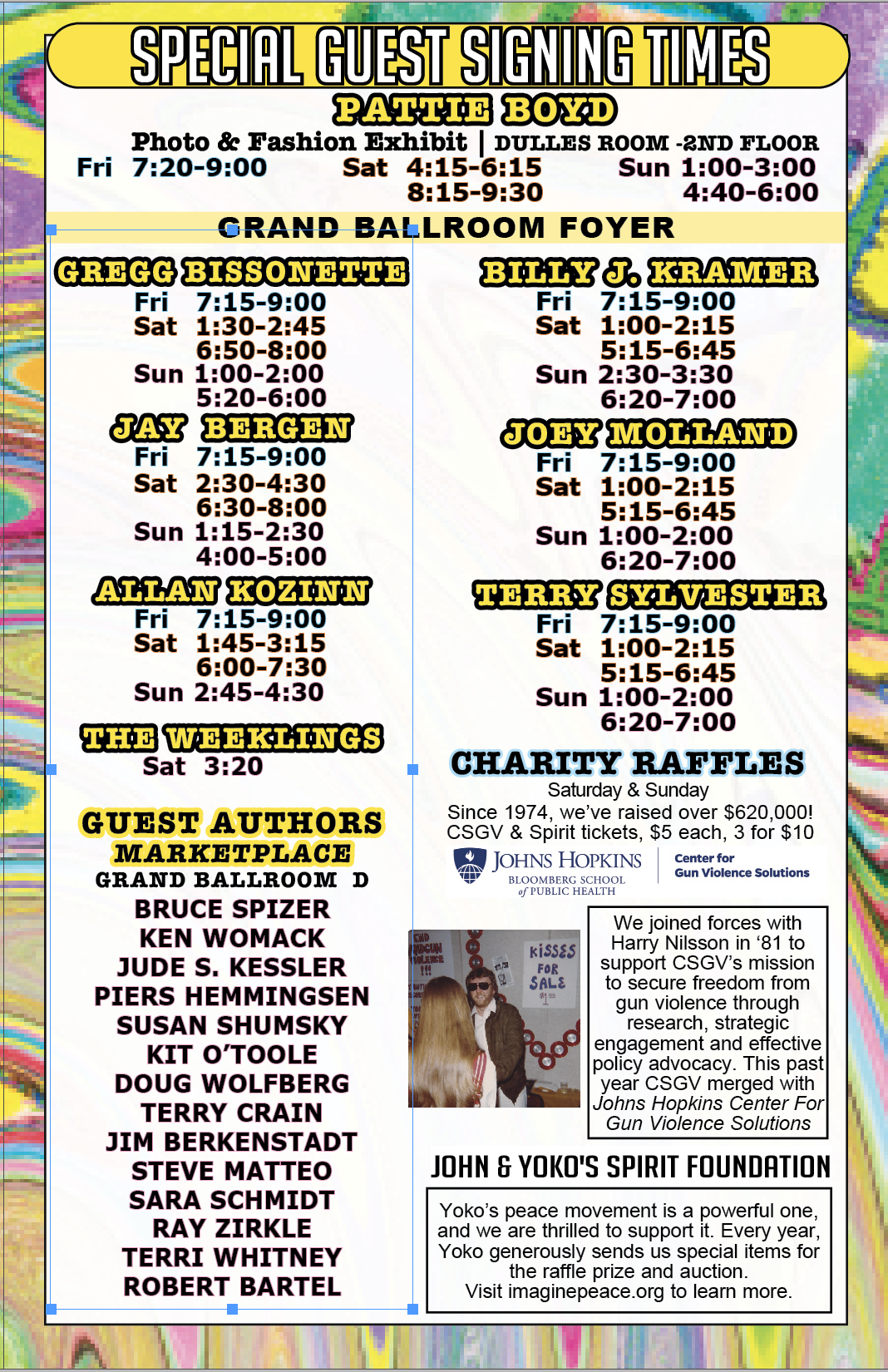

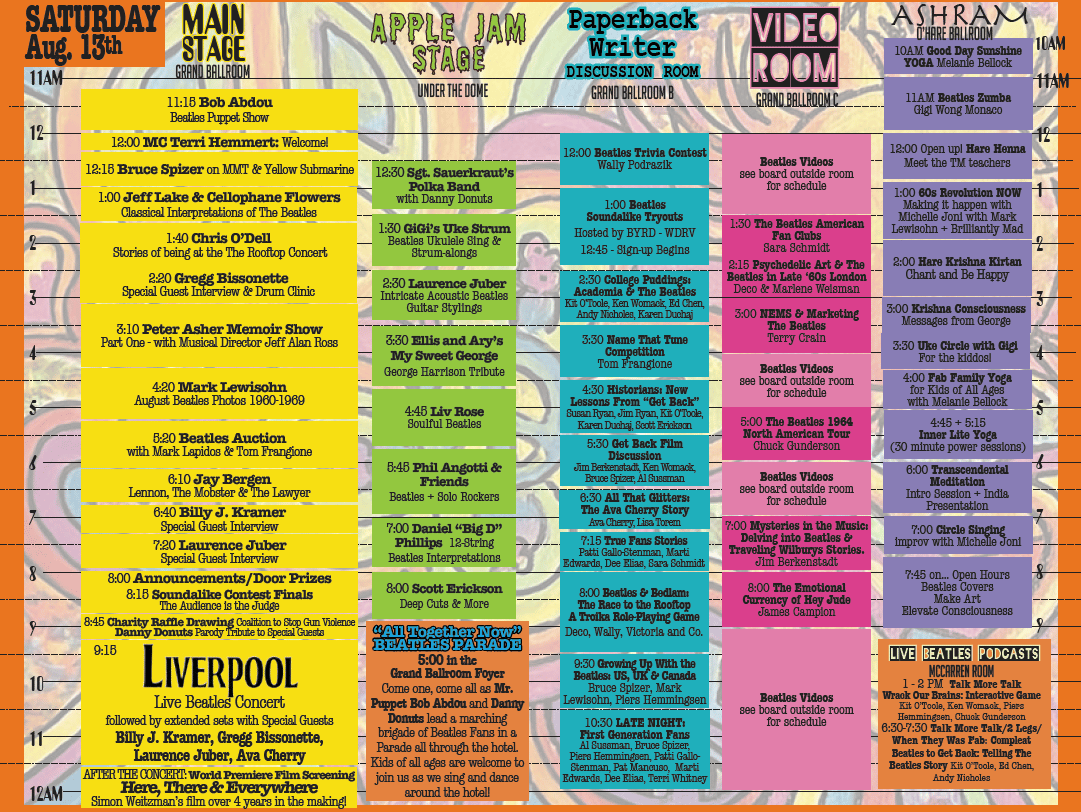

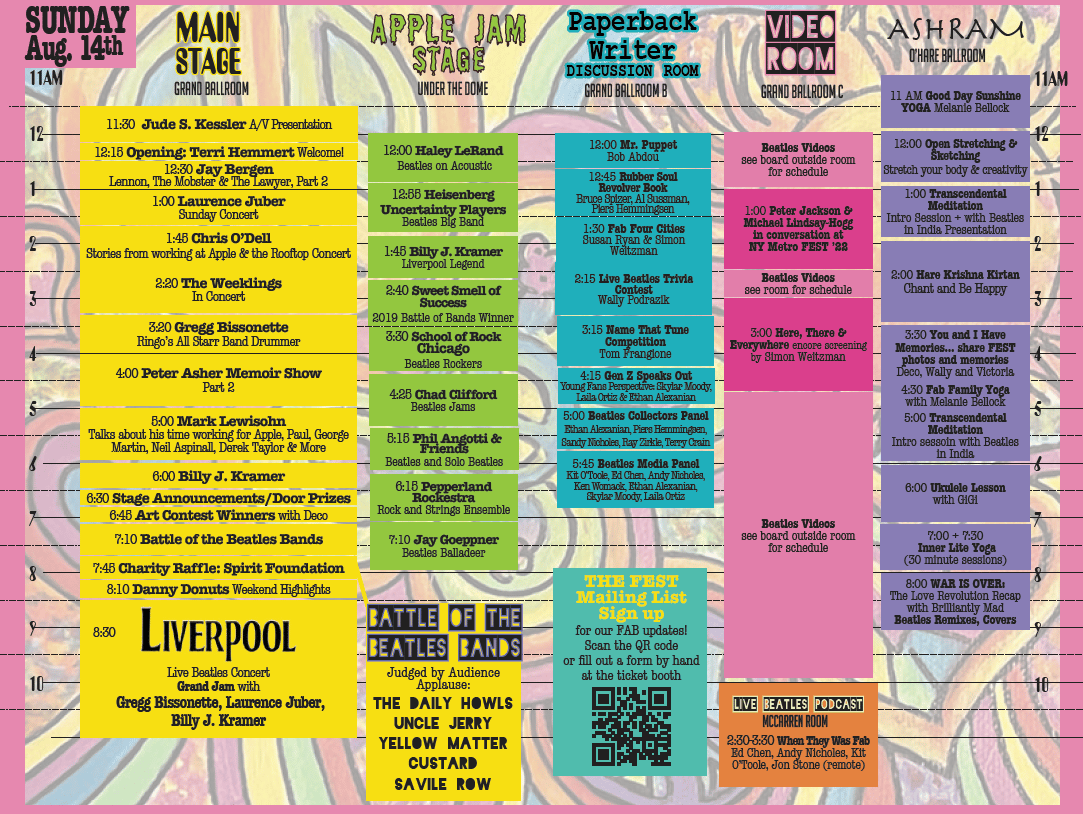

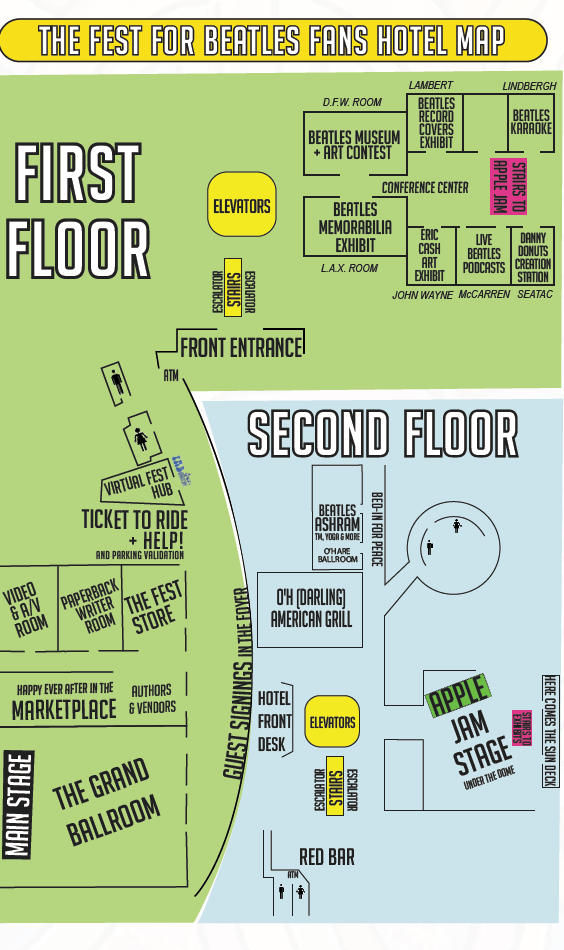

2024 NYC Fest Schedule of Events

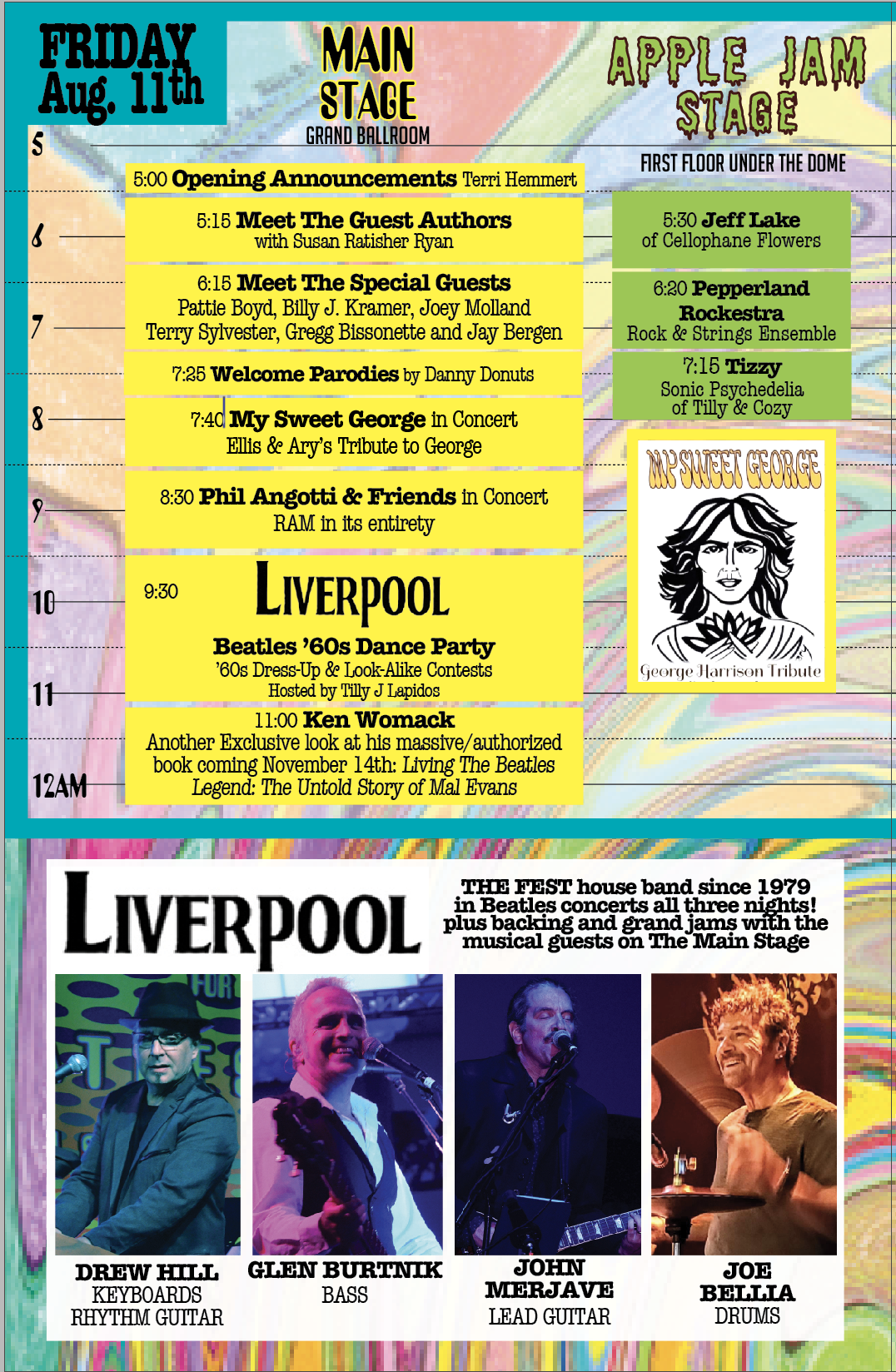

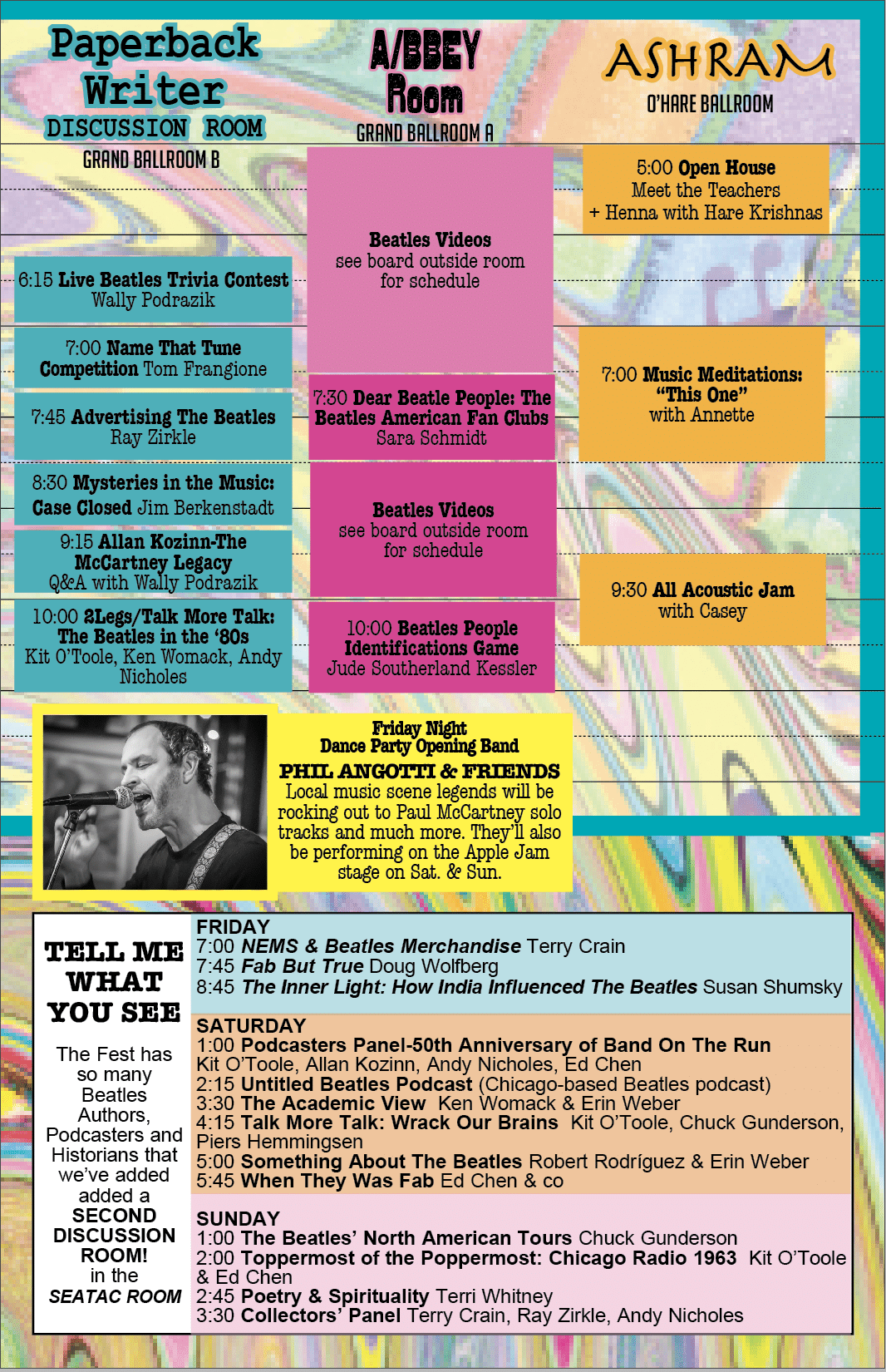

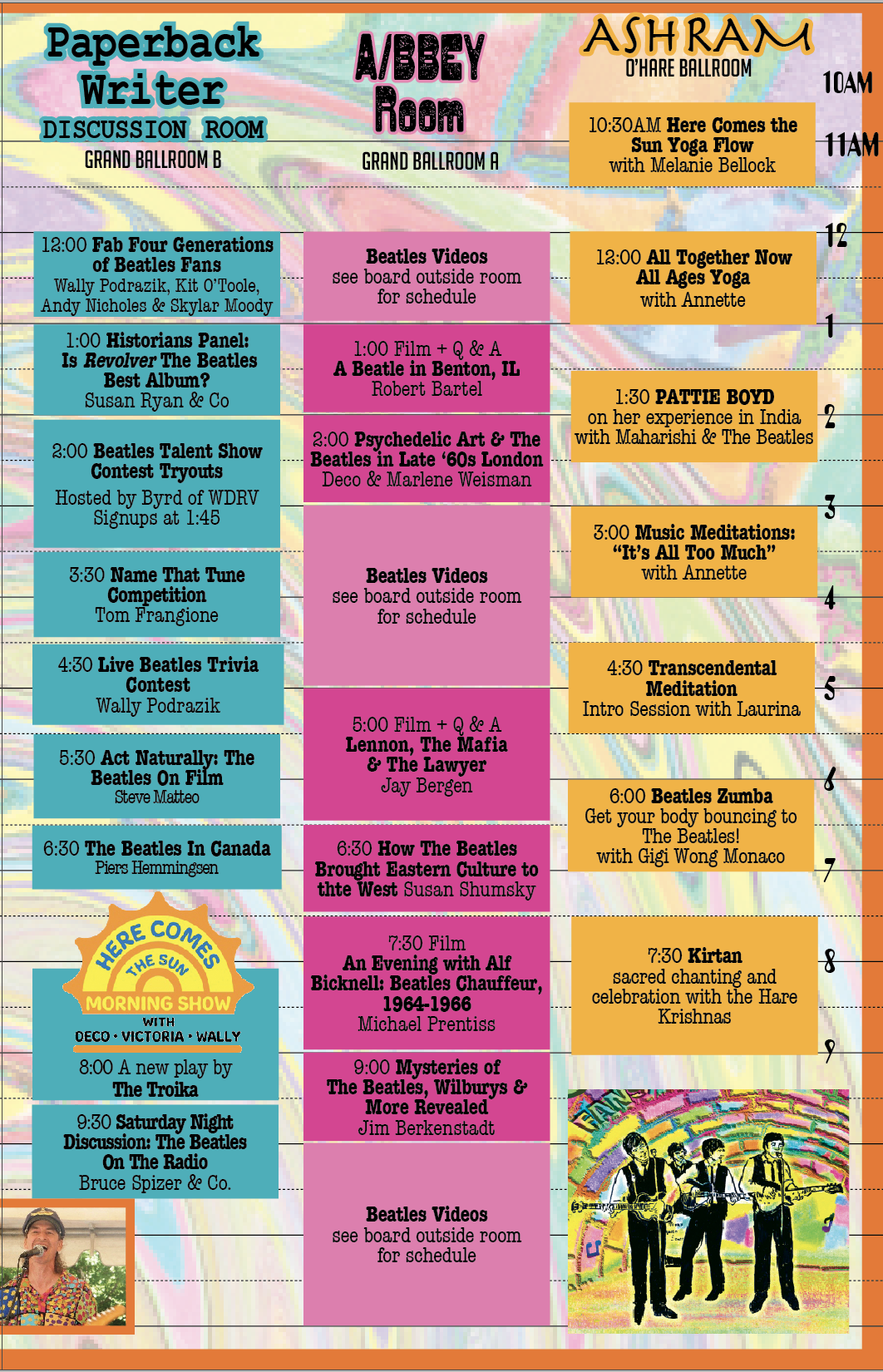

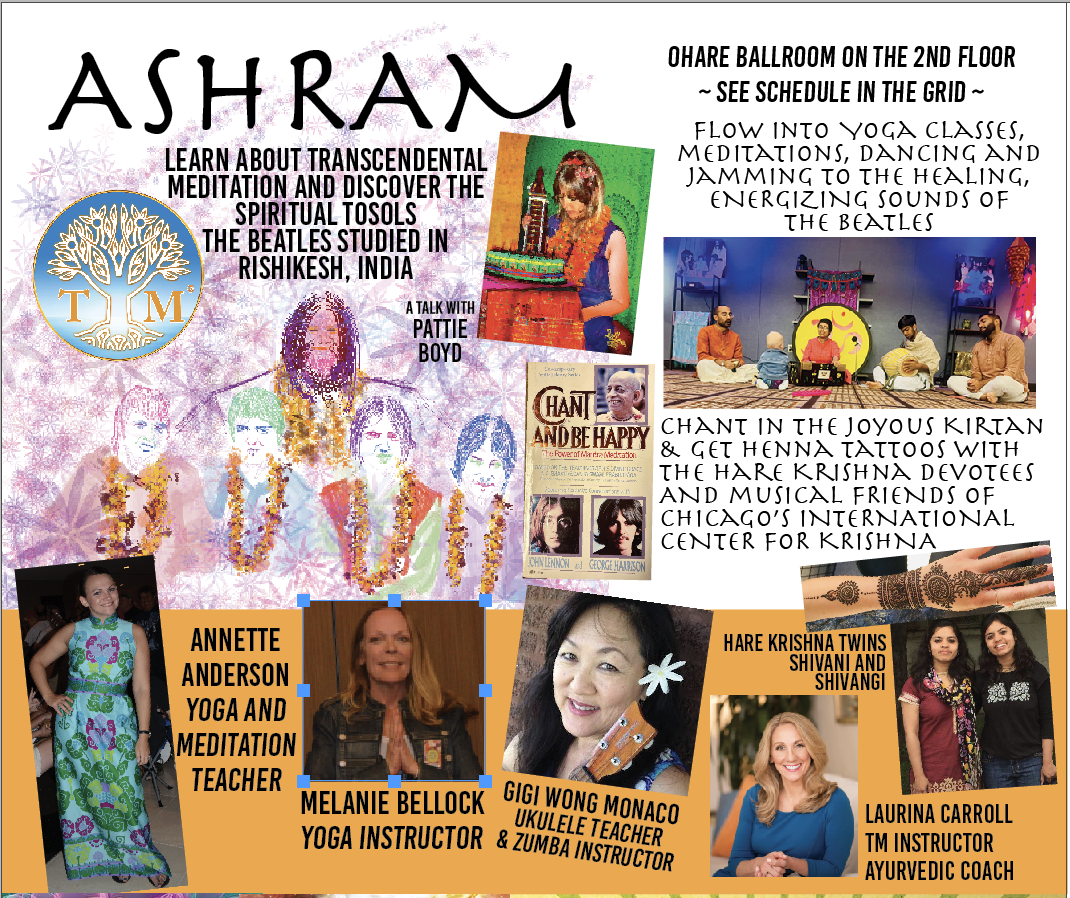

2023 Chicago Fest Schedule of Events

Revolver Deep Dive Part 5: Here, There & Everywhere

Revolver

Side One, Track Five

“Here, There And Everywhere”: In Which Paul McCartney “Obliterates Place”[i]

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Melissa Davis

Through 2023, the Fest for Beatles Fans blog will explore the intricacies of The Beatles’ astounding 1966 LP, Revolver. This month, Melissa Davis will provide our “Fresh New Look” at “Here, There And Everywhere,” the gorgeous song inspired by a particularly happy time in the romance of Paul McCartney and Jane Asher. Melissa was a member of the inaugural class of the world’s first graduate degree program concentrating on the musical and cultural impact of The Beatles, moving to Britain in 2009 and graduating from Liverpool Hope University in 2011. Her dissertation, A Contextual Analysis of the Reception of The Beatles in America, examined the questions: “Why then and why them?” Melissa has co-authored The Beatles Bibliography: A New Guide to the Literature (2012) and its 2013 supplement with Michael Brocken, founder of the first Beatles MA program. She is currently at work on the third volume of the bibliography.

Jude Southerland Kessler is the author of The John Lennon Series and a Guest Speaker at the upcoming Chicago Fest for Beatles Fans, August 11-13. She has written the “What’s Standard” and “What’s New” segments of this blog.

What’s Standard:

Recording Stats:

14 June 1966 – EMI, Studio 2 – 7:00 p.m. – 2:00 a.m. On this evening, 4 rhythm track takes were recorded, and vocals were superimposed onto take 4.

16 June 1966 – EMI, Studio 2 – 8:30 p.m. – 3:30 a.m. The decision to start the work over on “Here, There And Everywhere” was made. The boys began anew with take 5. By take 13, John C. Winn tells us “the bass, drums, and electric guitar rhythm track (with a second guitar playing volume pedal ‘swells’ near the end) was perfected.” Winn says Paul was singing a live guide vocal, which may have been redone later. (That Magic Feeling, 25) You can hear that “live guide vocal” on Anthology 2. Backing vocals were added during this session. At the close of this evening, Mark Lewisohn states, “A 14th take was created by reduction, onto which Paul superimposed his live lead vocal…” (The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 226) Womack goes on to say that Paul had varispeed recording applied to his vocal to manipulate the sound. ”Martin and Emerick recorded the track at a slower speed. During playback, varispeed recording [produced] a higher pitch – in this case, with the rendering of McCartney’s vocal at a higher frequency.” (The Beatles Encyclopedia, 386)

17 June 1966 – EMI, Studio 2 – 7:00 p.m. – 1:30 p.m. Paul added a second lead vocal to the final track of the song. He harmonized with himself on the second “love never dies” and “watching her eyes.” George added some lead guitar work. At the conclusion of this session, a rough mono mix was made.

21 June 1966 – further mixing of the song was accomplished.

Of Special Note:

Under the category of “What’s Standard,” we must not neglect to comment on The Beatles’ harmony. Paul, of course, is singing the melody line, but directed by George Martin, John and George are singing what Margotin and Guesdon refer to as “sumptuous vocal parts” (All the Songs, 333) Martin himself arranged these harmony lines, and they are performed beautifully. Such harmony may be standard – perhaps even “expected” – for The Beatles (think “This Boy” and “Yes It Is”), but their work is, nevertheless, breathtaking.

Tech Team:

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil MacDonald

Instrumentation and Musicians:*

Paul McCartney, the composer, sings lead vocal and harmony vocal. He plays his 1962 Epiphone ES-230TD Casino (some sources say “Epiphone Texan”) electric guitar with Selmer Bigsby B7 vibrato and his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass, using his 1963 Fender Bassman 6G6-A amplifier with cabinet.

John Lennon sings backing vocals and adds finger snaps.

George Harrison sings backing vocals, plays lead guitar on his 1965 Rickenbacker 360/12 12-string guitar and adds finger snaps.

Ringo Starr plays his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set, including brushes, and adds finger snaps.

*This information from Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 151-152.

Sources: Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 225-226, Lewisohn, The Recording Sessions, 83, Harry, The Ultimate Beatles Encyclopedia, 304-305, Womack, Long and Winding Roads, 140, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 332-333, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 25, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 151-152, Riley, Tell Me Why, 186-187, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 108, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 214, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 168, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 158-161, Mellers, Twilight of the Gods: The Music of The Beatles, 74-75, Everett, The Beatles as Musicians, Revolver Through The Anthology, 60, Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia, 386, Sheff, The Playboy Interviews with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, 152, and McCartney, Paul McCartney: The Lyrics, 272-273.

What’s Changed:

- A New McCartney “Personal Fav” – Paul states that of all the songs he’s composed “Here, There And Everywhere” is his all-time favorite, “with ‘Yesterday’ a close second.” (McCartney, The Lyrics, 273 and MacDonald, 168) Although MacDonald disagrees with this choice, stating that the sentimental lyrics render the song “chintzy and rather cloying,” McCartney would probably just shrug and respond, “You’d think that people would’ve had enough of silly love songs, but I look around me and I see it isn’t so…” Indeed, John Lennon said of “Here, There And Everywhere”: “That’s Paul’s song completely, I believe. And one of my favorite songs of The Beatles.”

- An “Overture”…or as Tim Riley phrases it, the tune’s “disarmingly simple four-bar introduction” (Tell Me Why, 186) – Many sources indicate that this is the “first time” that The Beatles have opened a song with an introductory melody and lyrics that will not be repeated again within the body of the song. However, that’s not quite true since John Lennon’s composition (performed by George Harrison) “Do You Want to Know a Secret,” opens with a brief overture: “You’ll never know how much I really love you/You’ll never know how much I really care.”

As Hammack points out in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, this technique is a throw-back to the classic songs that populated The Beatles’ youth, songs such as Harold Arlen’s “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” (p. 151) Indeed, Disney’s “I’m Wishing” (from Snow White) and Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas” were familiar “chestnuts” to the lads as well. Both featured preambles. But employed on a 1966 LP by the world’s most famous rock band, the renaissance of the “overture” stands as yet another innovation that makes Revolver so unique.

In Paul McCartney: The Lyrics, Paul reminisces that he was trying to imitate Cole Porter in “Anything Goes.” He explains, “…we were trying to emulate some of our favourite old songs that had a completely rambling preamble.” (p. 272-273) Hammack observes, “John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s ‘Here, There And Everywhere’ served notice that the duo could master any form they chose to explore.” (p. 151)

- Poetically Interlocking Lyrics – In The Beatles Lyrics, Hunter Davies extols the ingenuity of Paul’s manipulation of the words “here,” “there,” and “everywhere.” Davies says, “It’s easy to miss how clever the lyrics are. [McCartney takes] the three adverbs in the title, one by one, structuring the verses around Here, then There, and then Everywhere. He finishes the first line on ‘here’ and then begins the next line with the same word, and then repeats the same trick for the fourth and fifth lines with ‘there.’” (p. 158)

One might more accurately substitute the term “verse” for “line” in Davies’s quote, but whatever terminology one employs, Davies is correct. And in his 1980 interview with David Sheff, John Lennon admiringly noted Paul’s poetic technique. McCartney is consciously and poetically interlinking all space (“I need my love to be here,” “Nobody can deny that there’s something there,” and “I want her everywhere,”) and time (”hoping I’m always there”) into the ideal realm in which he wants his love to exist.

Tim Riley in Tell Me Why points out that when Paul steps into the “everywhere” segment, “the bridge leaps to a new harmonic ground.” (p. 187) This musical shift emphasizes the far-reaching implications of that highest, all-encompassing plane. Indeed, the shift from mere “here” and “there” to “everywhere” evokes a major chord – perhaps indicating that when his love is “everywhere,” all will be resolved.

- Special Effects – There are many brief but elegant “extras” in this song. Just before Paul sings, “but to love her is to need her everywhere,” listeners are treated to a guitar line that sounds very much like a mandolin. MacDonald notes that this was achieved “through the Leslie cabinet.” (Revolution in the Head, 168) And as the song plays out, Riley points out that “a descending French horn figure is added in the right channel.” (Tell Me Why, p. 187) This is achieved, MacDonald explains, “by use of the volume pedal.” (168) The song, of course, would have succeeded without these lagniappe flourishes, but empowered to experiment and embellish, The Beatles were lavish – pulling out all the stops.

- A Nod to Marianne Faithful – Some sources tell us that Paul worked to model his vocals after Marianne Faithfull’s soulful 1964 rendition of “As Tears Go By.” Listen and decide for yourself: https://tinyurl.com/bdy6ju6b

A Fresh New Look:

Jude Southerland Kessler: Although Paul was inspired by several other well-known artists in the creation of this song’s introduction and melody (to be discussed in the next few questions), the “love” to whom Paul writes is his girl, Jane Asher. Throughout 1964 and 1965, his songs for Jane had indicated trouble in paradise. In “You Won’t See Me,” “I’m Looking Through You,” and even “We Can Work It Out,” (“Love has a nasty habit of disappearing overnight”), we got the clear message that the two were at odds. Here, Paul’s message seems gentler and more hopeful. Was there a biographical reason for this change of heart?

Melissa Davis: Well, that sort of tells the tale right there, doesn’t it? As with all relationships over time, you fight, you make up, you break up, you get back together. The infatuation stage fades, and you begin to fully appreciate what the relationship and the other person bring to your life. Some couples get married. To each other. Some don’t. It’s a maturing process both individually and within the relationship.

Paul moved into the London home of Jane’s parents six months after they met in April 1963 when she had just turned 17, and he was not quite 21. While John was already married and a father, George and Ringo shared a bachelor apartment, spending much of their free time enjoying Swinging London. The Asher home was better suited to McCartney in that it offered a combination of the family atmosphere he craved, music (Mrs. Asher had taught George Martin at the Guildhall School of Music) and an introduction to the sophisticated world of London’s theater, art and music scenes.

But despite having a home base, McCartney was still very much a working Beatle contractually committed to writing and recording singles, albums and movie scores, filming a new movie a year, making television appearances, and, of course, touring with his mates – hardly conducive to a steady romantic relationship. Just as in any relationship, especially that of young people still living at home, Jane and Paul would have their ups and downs. Complicating matters was Jane’s desire to pursue her acting career and the added fact that Paul McCartney just happened to be the most eligible bachelor in the world.

The songs noted in the question reflect the spats, fights, break-ups and make-ups that all couples face, but Paul had the gift of being able to use them as inspiration for lyrics to express his emotions almost in real time.

When “Here, There And Everywhere” was written in mid-June 1966, Paul was in the process of rehabbing the home he had purchased at 7 Cavendish Avenue in St. John’s Wood. According to Peter Brown in The Love You Make (2002), “Instead of turning the decoration over to professionals, they decided to furnish it themselves. They took pleasure in shopping for each piece individually, sometimes buying used furniture at secondhand shops…”

So, we can guess that the time around the composing and recording of “Here, There And Everywhere” might have been a particularly happy time for the couple, looking forward to moving out of Mom and Dad’s and into a home of their own!

Kessler: By 1966, the Beach Boys and The Beatles had supposedly entered into a symbiotic-creative relationship. How did that inspirational association affect “Here, There And Everywhere”?

Davis: As an original generation fan, I experienced the Beach Boys and The Beatles contemporaneously. I was a kid, but my college-aged brother had a band that was headquartered at our house and rehearsed in our living room, and I benefitted from exposure to all kinds of great music that most of my friends didn’t have in their home.

The retrospective narrative (with a liberal dose of revisionist history thrown in for good measure) has had the Beach Boys moving from cars, girls, and surfboards to innovation in the studio combined with deep and mature lyrics that not only put them on an equal basis with The Beatles, but inspired Revolver and, according to some, made Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band possible. The reality in 1966 might not have matched such generous re-appraisal.

Yes, yes, I know. I’m familiar with Paul McCartney singing the praises of Brian Wilson and Pet Sounds. I also know he has a tendency to sometimes remember things as he wishes they had been rather than as they were or altogether misremembering them, e.g. the origin of the name Eleanor Rigby. But I am sure he feels genuine respect for Brian Wilson’s genius.

No one loves to sing along in the car with “I Get Around” at top volume more than I do, but with all due respect… I have a confession to make: I don’t buy the hyperbole.

The Beach Boys were AM radio; The Beatles were singles, albums, and movies. The Beatles were men; the Beach Boys were… well, boys. Brian Wilson may have been born a mere two days after Paul McCartney in June 1942, but he was still a ‘boy’ in a band with his younger brothers.

1964 was the year of The Beatles. The year of Beatlemania. They came to America, launched The British Invasion, and popular music shifted in a matter of weeks. Billboard’s 1963 Year End Top 100 featured a healthy contingent of R&B and Motown, but otherwise consisted of a mélange of folk, light pop, country (Johnny Cash), crooners (Nat King Cole, Johnny Mathis, Al Martino, Steve Lawrence, and Tony Bennett all had records in the top 100 that year), Henry Mancini instrumentals, foreign language (“Sukiyaki,” and “Dominique” by the Singing Nun) and even novelty (“Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah”). Surf was only a sliver with five records in the Billboard Top 100 for the entire year of 1963; the Beach Boys hadn’t had a #1 at that point, despite releasing singles since 1961.

To say The Beatles dominated the charts in 1964 is an understatement. Much has been made of the fact that by first week of April, The Beatles held the top five singles on the U.S. charts. This overlooks the additional seven Beatle singles in the Top 100 that week; two more records were songs about The Beatles. They also had the top two albums. They replaced themselves at the top of the charts. Three times.

The Beatles set fashion trends around the world and not just with teenagers; the Beach Boys wore dorky clothes and had unfashionably short hair.

The Beatles made movies that premiered with royalty in attendance. They had been recognized by the Queen. Most Americans mistook the MBEs for knighthoods, but it was still a step beyond anything accorded other groups.

Reporters queried The Beatles about the Warren Commission Report and the war in Vietnam. The Beatles forced desegregation at their concerts in the South. No one cared what other groups thought about much of anything.

In the summer of 1964, The Beatles starred in their first movie, garnering unexpected rave critical reviews (and that opening chord in “A Hard Day’s Night!”). Then, they toured internationally (Australia!).

Brian Wilson suffered a nervous breakdown at Christmas 1964, less than ten days after Beatles ’65 was released in the U.S. (Beatles For Sale in the U.K.). I’m not saying the two events are exactly related, but… there is much anecdotal comment from their contemporaries, professional musicians who felt the overwhelming pressure of competing with The Beatles, especially when it came from record label executives or a demanding manager.

The Beach Boys Today! was released in March of 1965, with the singles “Help Me, Rhonda,” “Dance, Dance, Dance,” “Do You Want To Dance?” and “When I Grow Up To Be A Man.” The Beach Boys were singing adolescent lyrics about dancing and growing up like “Wouldn’t it be nice if we were older…”

Beatles For Sale/Beatles ’65 featured “I Feel Fine” and “She’s A Woman,” “No Reply,” “I’ll Be Back,” “I’m A Loser,” and “I’ll Follow The Sun.” All about slightly more mature relationship issues.

The Beatles taped “Yesterday” for The Ed Sullivan Show the day before their August 15, 1965 Shea Stadium appearance. In a genre-shattering 2 minutes and 3 seconds, it blew down the limits of what popular music could be.

The Beach Boys Party! album came out three months later at the end of 1965. It was largely a compilation of covers (“Alley Oop,” “Papa Oom Mow Mow,” “Hully Gully”) and included three Lennon/McCartney compositions: “I Should Have Known Better,” “Tell Me Why,” and “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away.”)

Rubber Soul was released at the same time for the holiday season: “Norwegian Wood,” “Girl,” “In My Life,” and “Nowhere Man.”

Influence at the time seemed to be flowing east to west across the Atlantic.

By 1966, Brian Wilson was writing on pot; three of the four Beatles had taken LSD. In fact, when The Beatles were in Los Angeles during a break in their tour, the Byrds were invited over for music and acid. When David Crosby was spotted crouching behind a stage curtain during a press conference, John Lennon identified him to the press as, “our mate, Dave.” It was around that time that The Beatles publicly proclaimed the Byrds as their favorite group.

Despite the growth the Beach Boys were experiencing as Brian Wilson’s severe anxiety took him off tours and put him almost exclusively in the studio when he was able, The Beatles were featuring the sitar on a second song and constructing electronic tape loops for the finale to Revolver. They were grousing about British tax policy, musing about the loneliness of an old woman, and knowing what it’s like to be dead.

The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (recorded over a period of nine months from July 12, 1965 through April 13, 1966) was released on May 16, 1966. During that time, they released four singles: “The Little Girl I Once Knew,” “Barbara Ann,” “Sloop John B,” and “California Girls,” the last undoubtedly the one that influenced The Beatles’ “Back In The USSR” in late 1968.

Revolver was recorded from April 6 to June 21, 1966 (11 weeks) and released on August 5 of that year. In addition to “Here There And Everywhere,” Revolver gave us “Taxman,” “Good Day Sunshine,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Got To Get You Into My Life,” and “Tomorrow Never Knows.” It is simply in a class by itself.

Because the Beach Boys could not create the musical sounds Brian Wilson heard in his head, over 40 session musicians (including 25 members of the Wrecking Crew) and a 10-piece string section are credited with virtually all instrumentation on Pet Sounds. Revolver was recorded by the four Beatles playing their own instruments with the contribution of brass from Sounds Incorporated, an Indian tabla player on “Love You To” and a string octet on “Eleanor Rigby.”

Pet Sounds marked a departure for the Beach Boys from their own style and genre and opened their musical future to new possibilities; Revolver changed music for everyone and forever. The album was considered groundbreaking at the time it was released and influenced the groups and music that followed.

The year 1966 saw an explosion of new and immensely talented groups, many inspired by The Beatles. These groups were releasing innovative and exciting music featuring lyrics of depth, introspection and, in some cases, inexplicable meaning, which were intriguing and engrossing.

It’s important to remember contextually that the year of Pet Sounds was also the year of Simon and Garfunkel’s “I Am A Rock” and “Homeward Bound.” Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman.” Dylan’s “I Want You” and “Rainy Day Woman #12 and #35.” And if it was harmonies you wanted, one could feast on more Simon and Garfunkel, The Mamas and the Papas, The Hollies, The Lovin’ Spoonful, The 5th Dimension, and of course, the Byrds whose “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” and “Eight Miles High” were massive hits in both the U.S. and the U.K.

The Beatles’ shared love of harmony since their days listening to the Everly Brothers had resulted in years of singing, composing, performing and recording close, three-part harmonies, something The Beach Boys’ gorgeous vocals no doubt reinforced. After all, The Beatles were a group that loved covering girl groups, disregarding any awkwardness in four guys singing about boys with McCartney once saying the fun of it was “singing Bop-shoo-op-um-bop-bop-shoo-op with your mates.”

The Beatles were competitive among themselves, always trying to do better than their last record. That spirit, which Paul has long acknowledged, even vis-á-vis his songwriting partner, John Lennon, would have kicked in when they heard songs and albums they liked or they felt challenged them. So, yes… The Beatles listened intently to what was being recorded by other groups, and Pet Sounds must have been a spur for them, but not on Revolver. And it’s hard to see how Pet Sounds influenced “Strawberry Fields Forever” or “Penny Lane,” their first songs after Revolver, released while Pepper was in the works.

Pet Sounds did not do well commercially upon its release in the U.S. in May 1966; three singles gave it exposure (“Caroline No,” a Brian Wilson solo release that made it to #32; “Sloop John B” at #3, and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” at #8, with “God Only Knows” originally on the B-side).

As for “God Only Knows,” I’ve no doubt Paul loves it. I’m sure Paul does wish he had written the song. Who wouldn’t?

It’s a beautiful song. Its message is as romantic as “Here, There And Everywhere,” and McCartney is a romantic, “Helter Skelter” notwithstanding.

The song is critically acclaimed and universally loved. Bono says the song is proof of the existence of angels. Pete Townsend says it ‘still sounds perfect.’ Barry Gibb loves it. Jimmy Webb, who knows a little something about songwriting, calls it his favorite song. Even the critics love it.

Artists as diverse as Andy Williams, David Bowie, Glen Campbell, Elvis Costello and the London Symphony Orchestra have covered it. Most recently, someone (or someones) called Dr. Teeth and the Electric Mayhem recorded it. Versions in Spanish, Dutch, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Icelandic are available.

But the hyperbole, much of it stemming from McCartney’s well-publicized and genuine admiration of Brian Wilson and reverence for Pet Sounds, overstates the influence. I just take the now-assumed symbiotic relationship with a measure of salt.

That’s only my opinion. I love The Beatles, I’ve studied The Beatles, read and written about The Beatles. I’ve played their music (badly). Their music was sung at my wedding. It will probably be played at my funeral. Just a nice bookend. I’ve been steeped in them for almost 60 years. But that doesn’t mean everyone reading this won’t have their own opinions. We’re just lucky to have the music to disagree about!

Kessler: Fantastic observations, and so beautifully said, Melissa. As I researched the “What’s Standard” and “What’s New” segments of this blog, I found these words from Ian MacDonald in Revolution in the Head that second your emotion. He states, “However, while Pet Sounds, conceived of as a ‘reply’ to Rubber Soul deeply impressed McCartney and spurred him to better it in The Beatles’ next album Sgt. Pepper, Wilson’s masterpiece wasn’t issued in Britain until July. Even supposing him to have had an advance copy, no musical link exists between ‘Here, There And Everywhere’ and anything on Pet Sounds…” (p. 168)

So, moving on…

“Here, There And Everywhere,” as we indicated earlier, was one of John Lennon’s favorite songs. In fact, Paul says he received the rare “Lennon face-to-face compliment” for it. What do you think John liked and respected so much about this composition?

Davis: I think John would have noted the very personal lyrics of “Here There, and Everywhere” as this was a direction he had been heading, as well. Paul was writing about his relationship with Jane through good times (“Good Day Sunshine”), not-so-good times (“I’m Looking Through You”) and just plain confusing times (“You Won’t See Me”). John was sharing more of his own feelings in his lyrics (“Norwegian Wood,” “Nowhere Man,” “I’m Only Sleeping,” “Girl,” “In My Life,” and “She Said She Said”) and might have respected Paul doing the same.

John might also have rated the admission by another Liverpool lad that he needed this special woman in his life. Self-improvement would show up in the next album, Sgt. Pepper, in the form of “Getting Better.”

John undoubtedly would have appreciated the song’s melody and loved singing the harmony. It is an exquisitely beautiful piece of music that would have appealed to a man who had “Julia,” “Goodnight,” and “A Day In The Life” inside him, just waiting to be written.

Kessler: And finally, what do YOU like about “Here, There And Everywhere,” Melissa? Nearly sixty years after its release, is it still relevant and effective today?

Davis: I was in middle school (junior-high in those days) when I first heard this song and had been a devout “George Gurl” from the moment I “met” The Beatles on the first Ed Sullivan Show appearance on February 9, 1964. My friends all had their own favorite, of course, including one “Paul Gurl” who could never accept that he had a girlfriend.

We were just beginning to figure out what we would want in a boyfriend, and the song stated it as simply as possible: Paul believed he was better for having his girlfriend in his life. He needed her to be the man he wanted to be. What girl wouldn’t dream about her boyfriend feeling that way about her? What woman wouldn’t want a man thinking and singing those words? “Here, There And Everywhere” helped crystalize the concept of a love beyond “just holding hands.”

A few years later, Paul expressed the same sort of sentiment about another woman, his wife Linda, in the song, “My Love.” It is vastly inferior to “Here, There And Everywhere,” but the feeling behind it is from the same place in his heart. And, not coincidentally, “My Love” remains an unfailingly popular selection in his current touring setlist.

Years later, the introductory phrase (“To lead a better life, I need my love to be here…”) formed the basis of the famous takeaway from the film, As Good As It Gets, when Jack Nicholson tells the Helen Hunt character, “You make me want to be a better man.”

The song was played during a wedding scene on Friends, as certain a sign of cultural significance as any. No doubt it has been a part of many actual weddings and probably played a role in more than a few make-ups and proposals of all kinds in the past nearly sixty years. The emotion behind the singer’s acknowledgement of what his love means in his life and his honest declaration will always be relevant as long as people fall in love.

And then there’s the music.

“Here, There And Everywhere” is quite simply one of the best examples of what I think separates The Beatles from many of the excellent bands of that, or any other, era – the pure alchemy born of musicinstrumentlyricvocalmelodyharmonyemotionrhythmpoetrywitinsightselfawarenessfriendshiploveandjoy in just the right proportions almost every time.

Yes, all one word.

[i] In his work Twilight of the Gods: The Music of The Beatles, Wilfred Mellers pays this lovely homage to Paul McCartney: “If Love You To tells us how the love experience erases time, Here, There And Everywhere obliterates place.” (pp. 74-75)

For more information on Melissa Davis, go to:

e-mail: thebeatleworks@gmail.com

website: www.thebeatleworksltd.com

2022 Chicago Fest Schedule of Events

Beatles Poetry Contest: The Three Winning Poems

Since January 2021, we’ve been examining The Beatles’ 1965 work of genius, Rubber Soul, taking deep dives into each track. Having concluded Side One, this month we took a short intermission to stand, stretch, and have a bit of fun.

We invited Fest for Beatles Fans poet Terri Whitney — who has written two books of poetry on The Beatles and other rock’n’roll greats — to serve as one of the judges in a POETRY CONTEST in her honor: The Rockin’ Rhymer Poetry Contest.

Thanks to all who submitted poems. They were all wonderful.

Here are the three winning poems…

Sai Matekar, Winner

In My Life/ Two of Us (or 6th july, 1957, the birth of the Beatles)

6th July, 1957

Woolton church fete, on a beautiful sunny day

Life became a song,

When, John found Paul

Soulmate found soulmate

Music found magic,

Loss found love,

When Paths lead to home,

Wrong Words and banjo chords,

Found lost rhymes and a tuned guitar

Together came

Motherless sons, two

They, cried

Till nothing was left inside,

On a neverending night

Lines, in fully formed songs

Songs, in half written lines

Hands four played one melody,

Strings across searching eyes

Knee to knee,

Growing and healing

Memories,

Longer and

On a long road,

John hugged Paul

When the world changed

And they

Changed the world

When Paul hugged John,

On a road, long

and longer memories

Of healing and growing,

Knee to knee

Eyes searching, across strings

One melody played four hands,

Lines written, half in songs

Songs formed fully in lines

On a Night, neverending

Inside, nothing was left

Till they cried,

Two Sons,

Motherless

Came together

A tuned guitar and lost rhymes,

Found banjo chords and wrong words

Home lead to paths,

When Love found loss,

Magic found music,

Soulmate found soulmate ,

Paul found John, when

A song came to life

On a beautiful sunny day, Woolton church fete

1957,July 6th

Phillip Kirkland, First Runner-Up

THE LIFE OF JOHNNY (ABRIDGED)

Born of Mother (partly timey)

Virtual Orphan, Mimi cares

Wayward Johnny, daily howly

Auntie living deep despairs

Cocky muso young McCartney

Teaches roughneck, tuney strings

Jam together, fledgling combo

Rock ‘n’ Roll ‘n’ Blues ‘n’ things

Off to Hamburg, popping Prellies

Playing socks off, kiddies’ cheers

Man, we’re groovy little group now

Playing Cavern, Epstein hears

Richly contract, muchy money

Funny haircut, shiny suit

Liddypool is distant memory

Muchy fame and girls to boot

Arty Yoko, avant gardly

Wide-eyed Johnny, falls in lust

Beatles crumbly, end of era

Golden Apple turns to dust

Uncle Sammy, John and Yoko

Little Sean and baking bread

Starting Over, not for muchly

Mad assassin – Johnny’s dead!

Presley Moffett, Second Runner-Up

Like Mother, Like Daughter

Like mother, like daughter

Music is our common bond

And every moment in our lives is connected to a song

Mom gave me her copy of Sgt. Pepper

She bought the record

Sometime in the ’80s

The vinyl was missing, but the cover was still intact

She gave it to me and said, “I have listened to this album since I was your age in fact.”

Like mother, like daughter

Music is our common bond

And every moment in our lives is connected to a song

On the way to elementary school

Mom and I would listen to the 1 CD

It became a daily ritual

Driving down the street

Me singing my heart out in the backseat

We didn’t have real microphones

So we just used our hands, you know

Like mother, like daughter

Music is our common bond

And every moment in our lives is connected to a song

Even years later

I’m in college about graduate

And we still listen to The Beatles in the car

As soon as the first note starts

We get lost in the lyrics and forget everything else

It’s truly an escape from the chaos this world creates

Like mother, like daughter

Music is our common bond

And every moment in our lives is connected to a song

Sometimes we fight because we care

Because we never want to hurt each other

Or be unfair but

With all the challenges we face

The Beatles have ultimately brought us closer together

Like mother, like daughter

Music is our common bond

And every moment in our lives is connected to a song

Life of George: A Beatles Birthday Celebration

2 PM: Scott Erickson

3 PM: Joe DeJesu

The Beatles in June: Shine On

::: By Jude Southerland Kessler :::

As we, here at the Fest, continue our look at The Beatles in their months together, we wish you all peace…not only globally, but locally. The traumatic stresses of disease, isolation, financial loss, injustice, and violence have shaken us all over the last sixty days. We face a world filled with need, fear, anger, and resentment. As we walk through June 2020, what can we learn from The Beatles in four of their Junes together? What advice might they silently offer us? Let’s find out…

June 1964 – After 13 long days absent due to illness, Ringo was finally prepared to rejoin The Beatles’ first World Tour. Collapsing amidst a photo shoot on 3 June, he’d endured a nasty bout of tonsillitis and 11 days in University College Hospital, London. Now, however, Starr was suited-up to fly Pan Am from London to Australia to reconnoiter with his Liverpool mates. During Ringo’s absence, Jimmie Nicol (an excellent drummer in his own right, who very fortunately knew all of The Beatles songs and wore Ringo’s exact suit size…see The Beatle Who Vanished by Jim Berkenstadt for more info) had been standing in (er, sitting in) for Starr in Holland, Hong Kong, and Australia. And so, for one brief day on 14 June…there were myriad publicity photos of The Beatles with two drummers! But right away, Richard Starkey was back on the podium, banging away and flashing his winning Scouse grin. His throat was still a bit ragged but his humour was intact. When a reporter asked him, “Do you think your tonsillitis might change the group’s sound?”, Ringo chortled and said, “Only for a few days when I can’t sing…if you can call it singin’!” And the Fab Four were reunited.

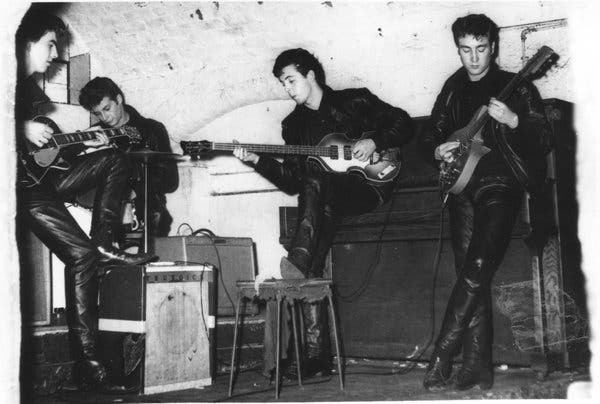

June 1966 – June was always Brian Epstein’s “month of choice” for World Tours. And 1966 was no exception to that rule. On 23 June, The Beatles left London Airport in Heathrow bound for Germany…the country where they’d cut their teeth as teenagers, performing in Hamburg. Their first night in Hamburg — August 1960 — the four Beatles (with Pete Best as their drummer) played to 6 very disappointed male customers who’d strolled down to the dark end of the Reeperbahn to see strippers — only to find 4 singing British boys instead! Somehow, The Beatles won over even those reluctant patrons, and in just a few weeks, the lads were so popular that they were promoted to a much larger venue: the Kaiserkeller. Now, two years later, John, Paul, George, and Ringo were billed as headliners in the stately halls of Munich and Essen, and tickets sold as quickly as they were printed. One reporter, disdaining the price of admission, callously asked John Lennon, “If you had to buy a ticket for your own performance how much would you pay for it?” John, in typical Lennonesque fashion, swiftly returned, “Oh, we know the manager, so we get in free.” The charm that had courted reluctant punters way back in 1960 was still very much alive.

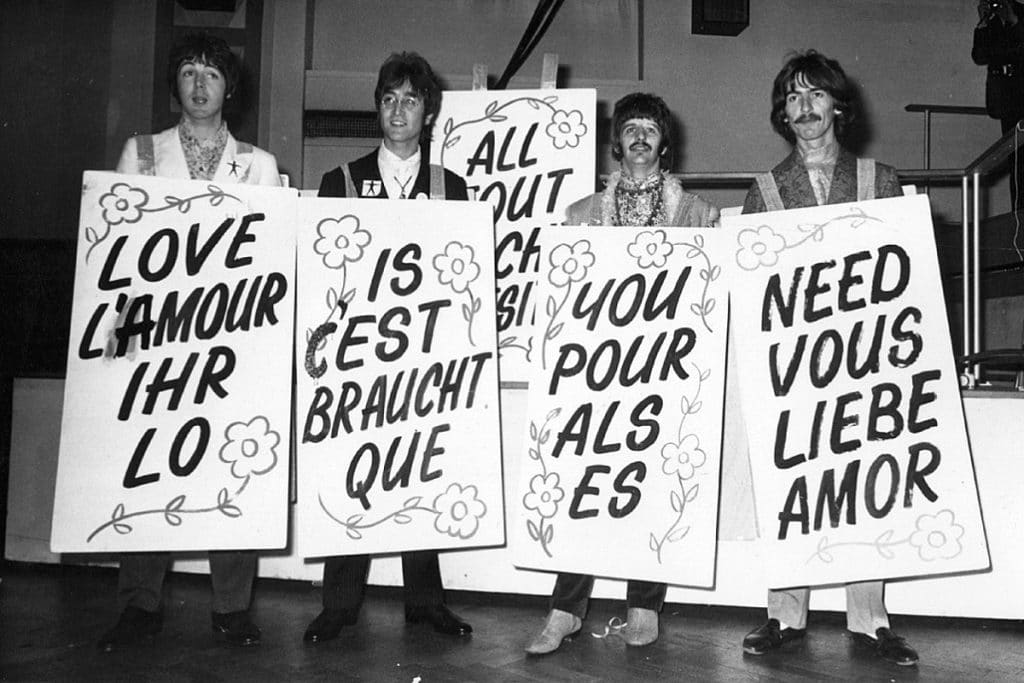

June 1967 – Done with touring forever, June of 1967 held not a World Tour this time, but a worldwide event! The Beatles had been chosen to represent Britain in the prestigious 25 June One World television special, slated to be broadcast live via satellite to 400 million viewers on 5 continents. And the song they’d selected to sing was truly, as Brian Epstein observed, “spine-chilling…the best thing they’d ever done.” It was, of course, John Lennon’s “All You Need is Love,” written specifically for the momentous affair. On 21 June, the boys began working on this landmark song in studio. Heads together as one, they prepared the anthem of peace, eager to send it out to a world heavily laden with the Vietnam conflict, Civil Rights unrest, military coups, wars, and entrenched divides. With a deep longing for concord, the boys tried to convey a simple message that would speak to all nations. As John later said, “It was a fabulous time…peace and love, people putting flowers in guns.” But as The Beatles, that night, focused globally and not locally, none of them realised that evening, that 21 June marked the very last time that Brian would ever be with them as they created in EMI. A pivotal moment went unnoticed.

June 1968 – After weeks and weeks of severe depression following John’s separation from Cynthia and from his son, Julian…weeks in which John Lennon actually contemplated suicide, the end of June 1968 found him finally rebounding with a new zest for life, as he prepared his You Are Here art exhibit slated to open on 1 July. The theme of the show was new beginnings and rebirth. As John and Yoko planned to dress entirely in white, to release 365 balloons to the world containing hopeful messages, and to zero in on John’s newly focused avant garde artiste side rather than his rocker image, “original” was the order of the day. John was, in effect, “starting over,” initiating a new life with a new lady at his side and a new message of peace. After months of agony, John had found a way to move forward.

You know, just when we think we’re alone in our struggles, we find it: the very mirror image of our griefs in the lives of John, Paul, George, and Ringo. The burdens we face, they faced. Every one.

Illness. Ringo’s ongoing struggles with health began early in life as he spent a myriad of formative years in sanitarium healing from the after-effects of a ruptured appendix and peritonitis. Then later, at age 13, he was back in hospital and long-term care again with complications from pleurisy and “effusion on the lung.” Even as a young adult, Ringo was frequently niggled with severe tonsillitis until he finally underwent surgery in December 1964. Yet rarely, if ever, do we hear Ringo complaining about the lost years in school with friends of his own age. Rarely does he moan over the lost days and weeks he might’ve spent with his family or the isolation of sanitarium life. Instead, he talks about the nurse who supplied him with a drum and the positive outlook those years gave him. To quote Hunter Davies in The Beatles, “[Ringo] never remembered himself unhappy. He thinks he had a good childhood.” (p. 148) Hmm!

Criticism. No one faced more venom from the press and public than The Beatles did. At first, journalists were gleefully “on board,” promoting and praising the British phenoms. But by late 1964, the press was hungrily seeking a chink in the Fab Armor. They were whispering about “Beatle dissention” and possible break-ups, about the Lennons divorcing, about unfair ticket prices and unkind treatment of the fans. The Beatles lived in a fishbowl, always under scrutiny. And for the most part, (yes, there were days when the boys, too, were resentful) they faced it all with humour and wit. Under adversity, The Beatles endured.

Global darkness. 1967’s grim world must have seemed unbearably oppressive to our boys. By June of ‘67, 448,800 young souls had been lost in Vietnam. June race riots in Detroit left 43 slain. Marches on Washington and rampant U.S. draft card burning events filled the headlines. In June, the Six Day War erupted in the Middle East, and the Nigerian Civil War boiled over in July. Turning their eyes globally, the boys might have missed the joys at their very elbows: the singular gift of a night in studio with their devoted manager, Brian Epstein. They might have been so intent on speaking out to a hurting world that they failed to treasure the simple and fleeting joys given to them, so close at hand. In this, too, there is wisdom for us to gather.

In each of these instances, The Beatles remind us to move forward…to keep reinventing ourselves, to keep pushing ahead. If one life phase subsides, then we can emerge into “Something New.” If the world threatens to overwhelm us, we can turn to those we love at hand. If we are heavy-laden, we can seek humor, music, faith, and friendship. We can work it out.

The Beatles never ever had a day without enormous obstacles to overcome: family losses, health challenges, public criticism, unrelenting work schedules. Yet, by simply putting one foot in front of the other, they kept going. It is a phrase we Beatles fans repeat without really thinking about it…but this month, we must make it our mantra: Shine On. You can do this, one step at a time. Shine on!

The Beatles: MAY-be I’m Amazed!

::: By Jude Southerland Kessler :::

The FEST for Beatles Fans has been tracing the “doings” of The Beatles, month-by-month, throughout their years together to see if we can glean a bit o’ wisdom from what “the lads” did in the seasons of their lives. From January’s events, we learned the value of industry and hard work. From April, we learned that suffering isn’t forever and will surely be followed by happier days!

What can we glean from the experiences that John, Paul, George, and Ringo shared in their Mays together? Well, let’s find out with John Lennon biographer, Jude Southerland Kessler…

May 1961 – The Beatles, in Hamburg for a second rollicking time, have been given the opportunity to actually cut a record — as a back-up band for headliner, Tony Sheridan. Though they were contracted to play at the Top Ten Club, the boys had been sneaking over to the Star Club, according to Tony Sheridan, and singing with the star on stage, and the Liverpool lads were quite popular there! As it happened, Sheridan — who had just been signed by music mogul, Bert Kaempfert, to a contract with Polydor Records — was looking for a back-up band to assist him with his first release. Naturally, he selected the popular Beatles and directed them to meet him “in studio.” Paul recalls, “We…expected a recording setup on a grand scale…Instead, we found ourselves in an unexciting school gym with a massive stage and lots of drapes.” But despite The Beatles’ clear disappointment, the boys (as The Beat Brothers) gave their back-up rendition of “My Bonnie” and “When the Saints Go Marching In” their all! And it’s THIS record — requested months later of Liverpool NEMS owner Brian Epstein — that induced Epstein to visit the Cavern Club on 9 November 1961 and “meet The Beatles.” That Hamburg school gym recording studio may not have been what the boys anticipated, but the results — which are still being felt today — were quite unanticipated as well! The modest recording studio led The Beatles down “a long and winding road” of lasting fame.

May 1964 – After completing their first film for United Artists, “A Hard Day’s Night,” The Beatles set out on some much-needed breaks. George and John, who’d decided to holiday together, traveled happily with John’s wife, Cynthia, and George’s girl, Pattie Boyd. Now, the concept of a yacht moored just off Papeete, Tahiti sounded divine after two long months of early mornings on set, 8-hour days filming, nights in EMI’s Studio Two recording a soundtrack LP, and many additional interviews and television shows sandwiched into the boys’ spare time as well. But once on board the rather ramshackle boat — with a sparse menu featuring primarily potatoes and a library with only one book (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) — John became fiercely bored. He discovered that he was much happier filling his days with creative work. So, he began writing songs (such as “Any Time at All,” for Cynthia) and penning pieces (“Snore Wife and the Seven D…”) for his second book, eventually entitled A Spaniard in the Works. George complained that John — who’d been going on for weeks and weeks about “needin’ peace” — now only wanted to work. It was what Lennon truly longed for — John found out.

May 1967 – After working for weeks on their most unusual and controversial LP to date, in May of 1967, The Beatles were releasing Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to a waiting world. And to celebrate what he thought would be the LP that encouraged his boys to brush shoulders with the public once again (perhaps even tour!), Brian Epstein celebrated via a lavish party in his Belgravia flat. Inviting in the “Who’s Who” of London, Brian expected John, Paul, George, and Ringo to serve as co-hosts — meeting and greeting the posh public. However, the boys arrived “rather out of it.” In fact, John — in a faux fur-lined, orange, print jacket — was deliriously giddy. Even Paul, who was customarily the group’s spokesperson, was rather agog that evening when an enchanting, blonde, American photographer he’d met four days earlier, Linda Eastman, knelt down in front of him to capture his picture. Deeply engaged in conversation, the two seemed quite taken with one another, and Brian was left to entertain his guests on his own.

May 1968 – Inviting his three friends to his Esher bungalow late in May, 1968, George Harrison anticipated a fun and relaxing afternoon. Sitting together on low, backless sofas, or wide, decorative cushions, The Beatles shared with one another the songs they’d been writing throughout the spring — both during their time in Rishikesh, India, and then back home in England. John demonstrated unpolished germs of remarkable songs. Paul offered up a tape of more perfected work. And George, wanting to remember the special afternoon, decided to record it all…just for fun. How surprised George would’ve been to see the impact of 2018’s remastered Esher Demos, his tape of that afternoon — the priceless seminal rendition of what would morph into the White Album. A lazy day shared by four friends in the British countryside was transformed: a priceless peek into The Beatles’ private lives and their methods of creating and recording music. What set out to be a jam session, more or less, ended up becoming a classic work of musical genius.

The Beatles’ Mays together seem to say one very Forrest Gump-ish thing, “You never know what you’re going to get.” Expecting Bert Kaempfert to afford them a lavish recording studio, the boys got a school gym recording space. Expecting that rather amateurish recording (so it seemed) to fall by the wayside, “My Bonnie” spawned sixty years of unequaled fame. Expecting a holiday on a yacht to calm his spirit, John Lennon discovered he craved work, and expecting an afternoon jam session to be just a bit of “in house” amusement, The Beatles inadvertently, “cut a record.” The boys’ days together in the “merry month of May” always afforded a wealth of surprises. Time and again, they were amazed…well, MAYbe.

Jude Southerland Kessler is the author of the John Lennon Series: www.johnlennonseries.com

Jude is represented by 910 Public Relations — @910PubRel on Twitter and 910 Public Relations on Facebook.