Revolver

Side Two, Track Six

“Got to Get You Into My Life,” An Ode To Pot

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Dr. Kit O’Toole

This month, the Fest for Beatles Fans Blog takes an in-depth look at Revolver’s “Got To Get You Into My Life.” Jude Southerland Kessler, our Fest Blogger and author of The John Lennon Series, pairs up with Dr. Kit O’Toole, author of Songs We Were Singing: Guided Tours Through the Beatles Lesser-Known Tracks and Michael Jackson FAQ: All That’s Left to Know about The King of Pop. O’Toole is also the co-author – with Dr. Kenneth Womack – of The Beatles and Fandom.

Besides being the co-host of the very popular Beatles solo podcast “Talk More Talk,” along with Ken Michaels, Kenneth Womack, Tom Hunyady, and Joe Mayo and co-host of “Toppermost of the Poppermost” with Ed Chen and Martin Quibell, Kit serves as Associate Editor for Beatlefan magazine. She contributes to many distinguished Beatles and music publications including Goldmine magazine, “Something Else Reviews” and “Blinded by Sound.” For years, Kit was a sought-after speaker at Beatles at the Ridge Authors and Artists Symposium, and in 2016, she was a Guest Speaker at the GRAMMY Museum of Mississippi Beatles Symposium. Most of all, Kit has long been a respected member of our Fest Family, taking part in numerous panels each year in Chicago and New Jersey. We are delighted to have her share her insights on “Got To Get You Into My Life” in the “Fresh New Look” segment of the blog.

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 7 April 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Three

Time Recorded: Evening Session from 8.15 p.m. – 1.30 a.m.

Technical Team

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72)

On this day: The Beatles had spent the afternoon and early part of the evening working on John’s “Tomorrow Never Knows.” At 8.15 p.m., however, they turned their attention to Paul’s new song, “Got to Get You Into My Life,” capturing 5 takes. Take One was a rhythm track with a one-note organ intro performed by George Martin, enhanced by Ringo on hi-hat. At this point, Paul seemed to be creating an acoustic number, a love song. Indeed, Paul’s bluesy outro was: “Got to get you into my life, somehow, someway,” with John and George responding: “I need your love.” By Take Five, this new love song had an organ introduction and was accompanied by full drums. As the evening ended, this take was marked as “best.” (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72)

Second Date Recorded: 8 April 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time Recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 9.00 p.m.

Technical Team

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72)

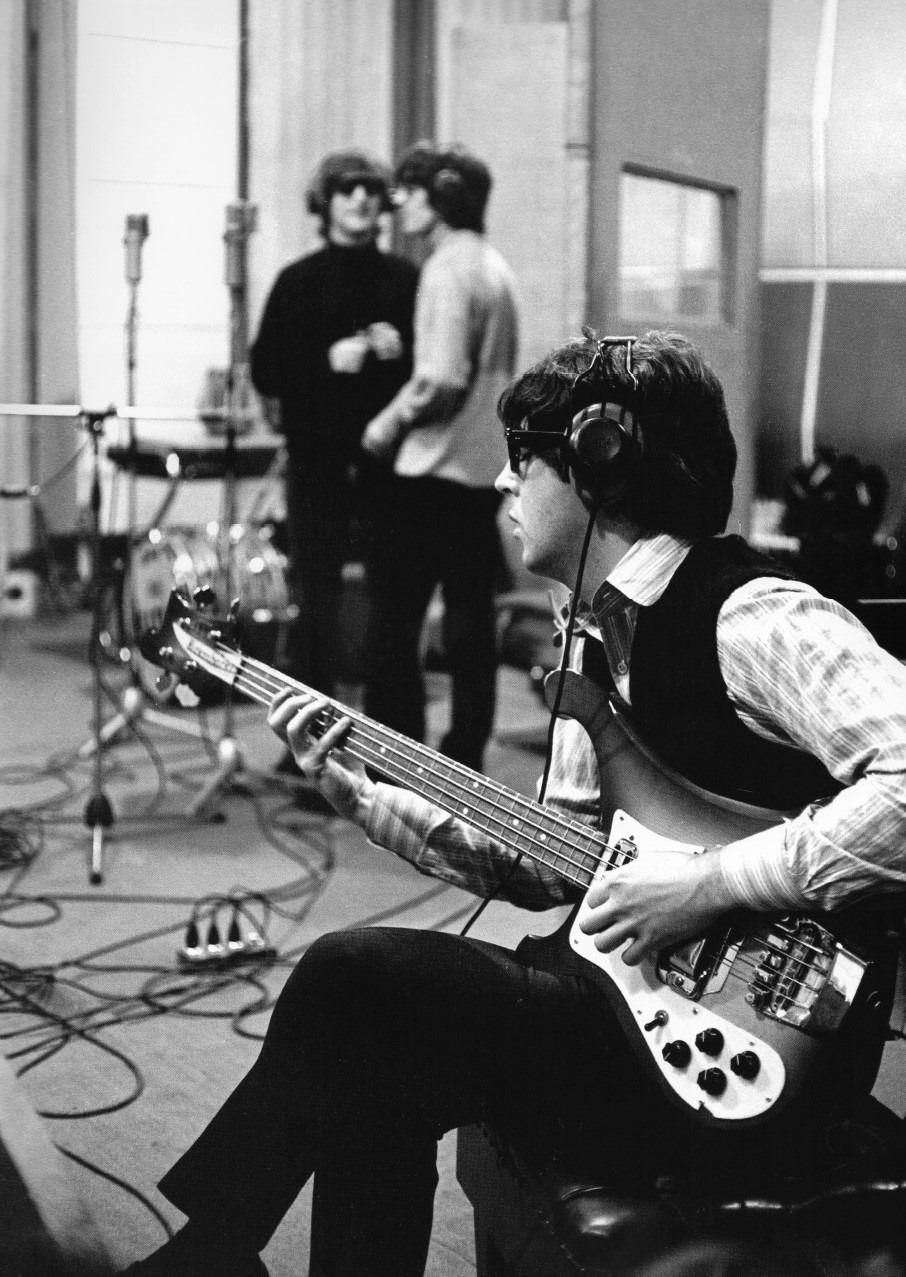

Since the “best” take (Take Eight) from 8 April is the one used for future superimpositions leading to the final product, the instruments that were used on this day are noted. In The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Hammack states that they were:

McCartney: 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass

Lennon: Vox organ (adds acoustic guitar on 11 April)

Harrison: one of the three guitars available in April 1966, including his 1961 Fender Stratocaster, 1964 Gibson SG Standard, or 1965 Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino

Starr: Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set

On this day: The Beatles tackled Paul’s new song again, slowing it down a bit to perfect the rhythm track. Winn in That Magic Feeling tells us that this version was “a slightly different arrangement.” Three more takes were attempted, and the last, Take Eight, was dubbed “best.”

Third Date Recorded: 11 April 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time: 2.30 p.m. – 7.00 p.m. (Time supplied by Lewisohn in The Beatles Recording Sessions)

Technical Team

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72)

On this day: According to Hammack in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, The Beatles returned to Studio Two to work on superimpositions for “Got to Get You Into My Life.” Hammack says, “McCartney added another bass to the song while Harrison added more guitar, and Lennon added more acoustic guitar using his 1965 Gibson Jumbo J-160E.”

Fourth Date Recorded: 18 May 1966

Place Recorded: Studio Two

Time Recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 2.30 a.m.

Technical Team

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72)

On this day: In a 12-hour studio session, “Got to Get You Into My Life” was completed. The vocals were overdubbed and extra instruments were added. But then, the song was dramatically altered. In Sound Pictures, The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, Womack tells us that “during the May 18 session, ‘Got to Get You Into My Life’ took a hard left turn from British pop fare into the world of American Motown…” (p. 79)

However, the product of this hard day’s night wasn’t a standard Motown or Stax song. Instead, Paul featured a brass blast, a front-and-center horn section. He composed a catchy big-band line, and as five gifted brass musicians looked on, Paul sat at the piano, demonstrating the notes he wanted them to play. As the quintet attempted to capture this sound, John listened from the booth, running out with a ”thumbs up” and vociferous “Got it!” when the sound was just right. And George offered input as well. Only Ringo, (we are told by Lewisohn) “was playing draughts in the corner.” (The Beatles Recording Sessions, 79) It was a Beatles group effort to create something very distinctive.

Sources:

Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 217, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 109-112, The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology, 209, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 111-113, Womack, Long and Winding Roads, 146, Womack, Sound Pictures, The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, 79-80, Harry, The Ultimate Beatles Encyclopedia, 272, Miles, The Beatles Diary, Vol. 1, 228-229 and 239, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 23, Gould, Can’t Buy Me Love, 363-364, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 216, Turner, Beatles ’66, 146-147, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 115, Turner, Beatles ’66, 260 and 261, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 26, 40, 44, 252 and 350-351, Riley, Tell Me Why, 197-199, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 154, Spizer, The Beatles From Rubber Soul to Revolver, 222, Everett, The Beatles as Musicians, Revolver Through Anthology, 38-39, Robustelli, I Want to Tell You, 49 and 63, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 176, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs, 95, and Mellers, Twilight of the Gods, 80-81.

What’s Changed:

- “An Ode to Pot” – Paul makes no bones about it: this song lauds the experience that produces “another kind of mind.” It’s a song about cannabis. This will be discussed in depth by Dr. Kit O’Toole in her “Fresh, New Look” segment, but failing to mention this theme here as a “changed” scenario in The Beatles’ catalog would be remiss.

John alludes to drug usage in “Dr. Robert” and “Tomorrow Never Knows” (the latter song will be discussed in next month’s Fest Blog), but this “ode to pot” is a first for Paul. (Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 176 and Spizer, The Beatles Rubber Soul to Revolver, 222) After initially disguising his subject matter with the trappings of a standard love song, McCartney eventually stripped away that façade and sang honestly about his enthusiasm for the inspiring effects of marijuana.

- A Motown/Jazz/Rhythm and Blues Number – By 1966, The Beatles had sampled myriad musical instruments: hand claps, maracas, harmonicas, tambourines, bongos, celestas, tape loops, a sitar, a Hammond organ, a sped-up piano that resembled a harpsichord or tack piano, and even a sweater stuffed inside the bass drum to produce a unique effect. In the summer of 1965, “Yesterday” had even featured an orchestral arrangement. Indeed, the desire to give listeners “something new” never diminished with John, Paul, George and Ringo. And as Spignesi and Lewis point out, “The Beatles were constantly pushing the envelope, testing their fans to see what they could get away with.” (100 Best Beatles Songs, p. 95)

Here, Paul does showcase “soul-style horns” that were inspired by “Memphis soul,” Atlantic Records, and Motown. Then, he added forcefully delivered lyrics that transformed the song into what Robert Rodriguez referred to as “an R&B-styled shouter, complete with the brass and production that Paul may have had in mind back when the band was still contemplating recording at Stax.” (Revolver, How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 111) In our “Fresh, New Look” segment, Kit will discuss the Stax/Motown influence in much greater detail. But it’s worthy of a mention in our “What’s Changed” segment that this sound was quite different from anything the boys had offered up previously.

Years later, one of the brass musicians, Peter Coe, recalled that, “The Beatles wanted a definite jazz feel.” But another musician, Les Condon stated: “The tune was a rhythm and blues sort of thing.” McCartney’s song combined elements from several genres, making it (in the words of Condon) both “interesting and unusual.” “Got to Get You Into My Life” was not a mere copy of anything – not the Memphis, Atlantic, or Detroit sound.

- The Use of “Outside” Musicians – Since George Martin’s early “wind-up piano” contribution to “Misery,” the Guildhall School trained musician had frequently contributed to Beatles arrangements and performances. But apart from the use of a studio drummer in the very early days, recruiting outside musicians to participate on Beatles recordings was a relatively new practice.[i] It dated back to June of 1965, when George Martin had convinced a very reluctant McCartney to permit a string quartet to supply the orchestration for “Yesterday.” (Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 252) In the spring of 1966 – welcoming outside performers to the collective was a still a rather bold decision.

The five gifted horn players recruited to perform on “Got to Get You Into My Life” were Eddie “Tan Tan” Thornton (trumpet) and Peter Coe (sax) – both of whom who hailed from Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames – Ian Hamer (from Liverpool, trumpet), Les Condon (trumpet), and Alan Branscombe (sax). (Rodriguez, Revolver, How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 112 and Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 79). Kit will discuss the contributions of Motown in the “Fresh New Look” segment, but the performance of these five musicians on this track certainly added that Memphis soul flair as well. They also unwittingly insured that “Got to Get You Into My Life” could never be performed on stage by the Fab Four. Paul could successfully perform “Yesterday,” without orchestration, but “Got to Get You Into My Life” was a Beatles track that could not be replicated by John, Paul, George, and Ringo alone.

However, afterwards, all four boys agreed that the end justified the means. Only four weeks after “Got to Get You Into My Life” was recorded, Paul permitted Alan Civil to add his elegant French horn to “For No One.” The way had been paved for later contributions by other “non-Beatle” musicians (Eric Clapton and Billy Preston, for example) to enhance the boys’ repertoire.

(Note: Paul often performed “Got to Get You Into My Life” with Wings in 1979. He used a four-piece brass section. WATCH HERE

- Diverse Reception – The reactions to this uncommon Beatles genre have been, through the decades, quite strong and diverse. Ian MacDonald in Revolution in the Head states, “Slightly out of his neighbourhood in this idiom, McCartney seems to have no idea how he wanted the song done, and it took two days of trial and errors to record the basic track…Leaving it for a month, he hired the brass…By this time, the production had become messy, with raggedly matched lead vocals and leakage from the brass onto one of the guitar tracks.” (p. 154) Similarly, Gould in Can’t Buy Me Love comments: “Revolver abounds in songs that were brought to life in the studio: this one was nearly done to death there…overshooting the idiom of soul music entirely, landing closer to the sophistication of big-band jazz at its blandest.” (p. 363)

However, Walter Everett in The Beatles as Musicians observes, “‘Got to Get You Into My Life’ has always been one of the LP’s most popular tracks; it rose to the Top Ten in July-August 1976 when Capitol released it as a single in support of a compilation LP.” (p. 39) Tim Riley in Tell Me Why says, “The vigorous horns, pulsating bass, knockabout drumming, and above all, the untamed Wilson Pickett vocalisms in the refrain echo the charged brilliance of the Motown and Atlantic labels…” (p. 198) And John Lennon, who quite liked the song, said, “I think that was one of [Paul’s] best songs, too, because the lyrics are good, and I didn’t write them.” (Miles, The Beatles Diary, Vol. 1, 228)

A Fresh, New Look:

We welcome our friend Dr. Kit O’Toole to the Fest Blog! At the recent Chicago Fest, Kit participated in a wide range of scholarly panels including “The Beatles Academic Panel (co-moderator with Ken Womack),” “Generations Panel,” “Media Panel (moderator),” “Toppermost of the Poppermost (co-host),” “Historians Panel: Yesterday IS Today,” and of course, the “Talk More Talk” panel on the topic “Wrack Our Brains.” Kit possesses expertise in music through the ages (from 1950 to today and from pop to classical) and an extensive knowledge of The Beatles. I’m looking forward to her “Fresh, New Look” at Paul’s “Got to Get You Into My Life.”

Jude Southerland Kessler: Kit, thanks so much for joining us for this month’s “Fresh, New Look” at Revolver’s “Got to Get You Into My Life.” If I’m not mistaken, this is one of your favorite tracks on the LP. Tell us (to paraphrase Ringo in Help!), “What first attracted you to this song?”

Dr. Kit O’Toole: I’m a huge fan of soul and R&B, as were The Beatles, so “Got to Get You into My Life” is right up my alley! One of my other favorite bands, Earth, Wind & Fire, covered the track years later, and I think it’s one of the best Beatles covers of all time. “Life” encapsulates everything I love about the band—their ability to take on a genre but make it entirely their own. They never simply copied a particular style—they incorporated their signature lyrics, voices, and instrumentation to create something new.

Kessler: In Ken Womack’s Long and Winding Roads, he points out that “Got to Get You Into My Life” “brilliantly captures the sound of Motown, especially the flavor of Supremes hits such as ‘Baby Love’ and ‘Where Did Our Love Go.’” (p. 146) Do you hear this, and if so, how do McCartney and The Beatles create the Motown overtones?

O’Toole: First, it cannot be overemphasized just how much Motown influenced The Beatles. As we know, Merseybeat groups were devouring American R&B as early as the late 1950s—Berry Gordy founded Motown in 1959, and he struck a deal with Decca’s London American imprint to distribute music in the UK (until Motown finally released music under their own label in 1965). Ringo Starr stated in the Anthology documentary that “when I joined The Beatles we didn’t really know each other, but if you looked at each of our record collections, the four of us had virtually the same records. We all had The Miracles, we all had Barrett Strong and people like that. I supposed that helped us gel as musicians, and as a group.”

The Beatles covered Motown tracks—on radio, at least—as early as 1962, when they performed “Please Mr. Postman” on the BBC show “Teenager’s Turn—Here We Go.” It marked not only The Beatles’ radio debut, but the first time any Motown track was aired on the BBC. That performance enabled Gordy to negotiate better UK distribution deals, as the Beatles essentially introduced the sound to the larger British public. As we know, the band would go on to cover “Money,” “You Really Got a Hold on Me,” and, of course, “Please Mr. Postman,” all for With the Beatles.

In Gordy’s autobiography To Be Loved, he recalled finally meeting The Beatles during a 1965 Motown Revue package tour. “While taking photographs together, I told them how thrilled I was with the way they did our three songs in their second album,” Berry wrote. “They told me what Motown music had meant to them and how much they loved Smokey’s writing, James Jamerson’s bass playing and the big drum sound of Benny Benjamin” (p. 210).

Indeed, Jamerson in particular played a huge role in Paul’s bass playing. As he learned the instrument, he listened to the melodic bass lines of Jamerson, even though Paul didn’t even know his name for many years. His jazz-influenced playing and distinctive bass lines in tracks such as the Temptations’ “My Girl” expanded the possibilities for bass players, teaching Paul to avoid stagnant, clichéd lines (for examples of Jamerson’s inventiveness, listen to Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” or the Four Tops’ “Standing in the Shadows of Love”).

Smokey Robinson and the Miracles were another influence, as demonstrated in Please Please Me’s “Ask Me Why.” From John Lennon’s falsetto to the backing vocals to the dramatic bridge (“I can’t believe it’s happened to me / I can’t conceive of any more misery”), Robinson and the Miracles’ style resonates through the track. As George Martin stated in the Anthology companion book, “In the early days they were very influenced by American rhythm-and-blues . . . They certainly knew much more about Motown about black music than anybody else did, and that was a tremendous influence on them” (p.194). The Beatles would prove it with the B-side of the “I Want to Hold Your Hand” single, “This Boy,” a close-harmony track which Harrison described as ”a song John did that was very much influenced by Smokey . . . If you listen to the middle eight of ‘This Boy,’ it was John trying to do Smokey,” he told Timothy White in his George Harrison Reconsidered interview (p. 23).

Fast-forward to 1966, and the Motown influence continued. For his “Paperback Writer,” Paul wanted a particular sound. “I need you to put your thinking cap on,” Paul told Geoff Emerick, according to the memoir Here, There, and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles. “This song is really calling out for that deep Motown bass sound we’ve been talking about, so I want you to pull out all the stops this time.” (p.114) According to Emerick, Paul was obsessed with the deep bass sound of Motown records and frequently challenged Emerick to duplicate that sound in Beatles recordings.

This brings us to “Life.” In a 1968, Rolling Stone interview with Jonathan Cott, John Lennon described it as “our Tamla Motown bit. You see, we’re influenced by whatever’s going. Even if we’re not influenced, we’re all going that way at a certain time.” The horns, the lush production—all reflected Motown at its best. Obviously, there were differences—to make the horns sound bigger, Emerick close-miked the instruments, applied severe limiting to the sound, then came up with the idea of “dubbing the horn track onto a fresh piece of two-track tape, then playing it back alongside the multitrack, just slightly out of sync” to create the effect of ten horns playing instead of five (Here, There, and Everywhere, p. 128).

The close-miking and double-tracking effect lent the horns a “dirtier” sound than a typical Motown production, but Paul’s cooing “oohs” recall a breezy Supremes vocal, the driving bass a touch of soul, and just the presence of horns a nod to the Funk Brothers. The growl behind Paul’s utterance of “Got to get you into my life!” may be a tip of the hat to Marvin Gaye. Overall, it demonstrates how The Beatles absorbed all the Motown records they had heard, put them in a blender with their own sound, and created a unique, infectious track.

Kessler: Every essay on “Got to Get You Into My Life” heralds George Harrison’s lead solo on his Sonic Blue Fender Stratocaster. John C. Winn in That Magic Feeling refers to it as “a brief but thrilling guitar solo” (p. 26) and Riley in Tell Me Why asserts, “This could well be George’s finest moment: the sound of his guitar is dazzling…” Tell us more about Harrison’s solo and how this remarkable sound was achieved.

O’Toole: In 2021, Guitar World magazine asked some of the world’s most respected guitarists to cite some of their favorite George Harrison guitar solos. David Grissom, who has played with such artists as John Mellencamp, the Chicks, and the Allman Brothers, cited “Life” as one of George’s best. “It was this song that started my infatuation with guitar,” Grissom said. “The lick that happens at 1:50 still gives me goosebumps. That Vox midrange and George’s soulful double stop bend on the second and fourth strings are as good as it gets.”

What Grissom describes is the fuzzy, distorted sound of George’s guitar and the piercing solo, and the bending of the notes during his solo. In contrast with the brassiness of the trumpets, these elements give a harder rock edge to the track. “Life” exemplifies “rhythm and blues” in every sense of the word—George’s riff and gritty guitar solo perpetuates the rhythm, offering a sharper, driving companion to the bright horns. The Beatles and George Martin could have easily stuck to the pure soul sound, but adding the crunchy-sounding guitar was a stroke of genius.

Kessler: Finally, you were the person who first alerted me to the fact that this song is (as Paul said in Miles’s book McCartney) “an ode to pot.” I always thought it was a love song. How did Paul reshape his original lyrics to tailor them to this unique subject matter?

O’Toole: In discussing the song with Barry Miles in Many Years from Now, Paul stated that he wrote “Life” when he was first introduced to pot. He found it easier to tolerate than alcohol and called it “mind-expanding” (190). The song, he added, is “not to a person, it’s actually about pot. It’s saying, I’m going to do this. This is not a bad idea. So, it’s actually an ode to pot, like someone else might write an ode to chocolate or a good claret” (190).

More recently, in The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present, Paul reiterated that when writing the song, he consciously wrote lyrics addressing his newfound love of marijuana. He cited the specific lyrics “I was alone, I took a ride / I didn’t know what I would find there” as representing the “joyous” and “sunny-day-in-the-garden” experience of the time (p. 1954). Indeed, an ode to pot would prove too controversial for mainstream audiences, so Paul composed lines that could be interpreted as being in an altered state romantically or chemically.

Upon first listen it sounds like a bouncy love song, but a closer analysis of the lyrics reveals something else beneath the surface. The narrator, alone, seems to enjoy a car ride. But here’s the key line: “Another road where maybe I could see another kind of mind there.” This is a ride of another sort: a journey of the mind, a hallucinogenic ride. The horn blasts represent joy, a high of a sort. After this experience, he wants the experience “every single day” of his life. Next, he personifies pot, claiming that unlike others “you didn’t run, you didn’t hide,” and he wants to hold not only the pot itself but the hallucinogenic experience. “You were meant to be near me,” he declares, and reiterates that they will be together every day (note that the beloved never speaks, the narrator says he wants it to hear him).

The next verse again suggests that the narrator is in love with an experience, not necessarily a person: “When I’m with you I want to stay there / If I’m true I’ll never leave / And If I do I know the way there.” In other words, he’s reluctant to return to the “real world,” instead lingering in this dream state. As the song ends, however, he reprises the opening lines about taking a ride and “suddenly seeing” his beloved — or, as Paul later clarified, marijuana. In other words, he knows he can re-experience the high any time he wishes to escape. What an interesting choice to use the language of soul music to express his desire for pot!

Kessler: So interesting! Thank you, Kit, for your insights, and for those of you who haven’t yet enjoyed Kit’s book Songs We Were Singing: Guided Tours Through the Beatles Lesser-Known Tracks, this is the sort of excellent information you can expect for each of the “umplumbed” songs she discusses. Kit, thanks very much for being with us for The Fest Blog this month, and we’ll see you in March for our big New York Metro Fest.

For more information on Dr. Kit O’Toole, HEAD HERE

Connect with Kit on Facebook HERE

Come meet Kit and Jude in person at the

New York Metro Fest for Beatles Fans

March 28-30, 2025 at the Hyatt Regency Jersey City

[i] Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 40 and 44 and Robustelli, I Want to Tell You, 49 and 63. According to Robustelli, session musician Andy White did play drums on version 3 of “Love Me Do” (Margotin and Guesdon say version 2) and drums on “P.S. I Love You,” (Margotin and Guesdon say bongos) but this was not a group decision but rather the decision of George Martin. A studio drummer was also used once to perform fills during the making of “A Hard Day’s Night” in 1964 when the boys were too busy to return to studio. But once again, this was not the decision of John, Paul, George, and Ringo.