Revolver: It was a serious LP about solemn issues, and no song expressed the theme of this album better than “Eleanor Rigby.”

Ah, look at all the lonely people!

That formal “Greek chorus” opening the song boldly announced to us all the “grand motif” of the songs that would follow (and repeated the theme of “Taxman,” which had just preceded it). “Ah, look at all the lonely people!” It was Revolver’s seven-word synopsis, in all its intricacy and creative glory.

So why is “Eleanor Rigby” not the opening song on the LP, then? Why is it placed as the second track on the record?

For the listener, “Taxman” is the equivalent of a novel’s “hook,” that exciting chapter that draws the reader into the book at large. But then, in Chapter Two – in “Eleanor Rigby” – the reader settles into the narrative and begins the book in earnest. He or she takes a breath, sits back, and listens…begins to pay attention and absorb the theme of what is to come.

“Taxman” immediately grabs our attention, but in “Eleanor Rigby” (to the moving, poignant sound of a string octet [1]), we are given a quiet moment to stop, think, and preview every single issue to follow on this album: isolation, loneliness, love desired, love denied, and finally, death. In the storied lives of Eleanor Rigby and Father McKenzie, we get a glimpse of all this is to come: the irreparable heartbreak in “For No One,” the aching need and hunger in the seemingly jaunty “Got to Get You Into My Life [2],” the anger in “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and even the deep depression of “She Said She Said.” It’s all there.

For The Beatles, this song couldn’t have come at a better time. A fissure was on its way to becoming a cleft (bass and treble), and the cleft would eventually become a split. But right now, it was only a fissure. Barely there, and yet, still a problem. But magically, this lovely song about isolation and loneliness, for a time, bridged that fragile gap and brought The Beatles close together again. If only for a short time.

They met at John’s Kenwood and began tackling “Eleanor Rigby” as a team. Paul had already developed the basic melody, but many of the lyrics still eluded him. The central character (eventually Eleanor) had inadequately evolved from “Ola Na Tungee” to “Miss Daisy Hawkins” without Paul’s feeling that this was right [3]. And similarly, he was searching for a story about the parish priest. And so, he left London behind and went out into the night, in search of a little help from his friends.

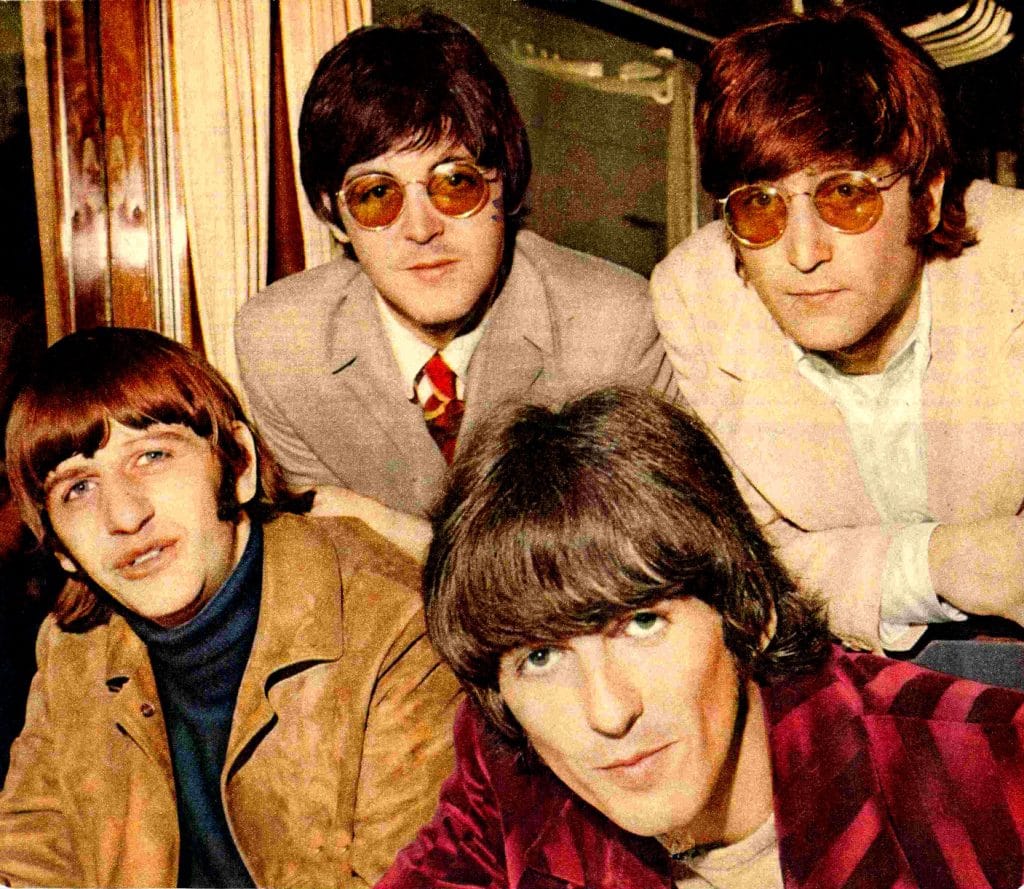

According to Pete Shotton, when Paul arrived at John’s “Kenwood,” John, George, Ringo, and Pete were all there [4]. John, bored with the telly, suggested they all go up to his recording studio “’n play a bit of music [5].” And that is when Paul offered up “this little tune here [that] keeps poppin’ into me head, but I haven’t got very far with it [6].” And so the lads listened…and began to offer suggestions.

Pete pointed out that the fans would “think that’s your poor old dad” in the song “left all alone in Liverpool to darn his own socks [7].” And alarmed, Paul quickly agreed: they needed a new name for the lonely cleric. So Pete, thumbing through a phone book, began to call out Mc-names to the gathered group. “McVicar?” he shouted. Hilarious…and so, not appropriate for the song’s disposition. “McKenzie?” Right. It fit the melody’s patter, and besides, they’d once known that Northwich Memorial Hall compere, Tommy McKenzie. “Good man – Tommy!” one of them said. “Yeah, right, give the lad a nod!”

So Father McKenzie it was…a holy man wholly alone, solitary, and brooding. But doing what exactly? “Darnin’ his socks in the night,” Ringo suggested. “Yeah, right!” “That!” And it was adopted on the spot.

“Writin’ sermons that no one will hear,” John claimed to have added later, in a room alone with Paul [8]. And that, too, became part of the song.

It was George, however, who suggested the most memorable line of all: “Ah, look at all the lonely people [9].” A simple phrase. Perfect. It spoke eloquently of solitary Eleanor, unloved and unlovely, picking up not her bouquet, but fallen rice littering an empty church where a wedding had been. It captured the spirit of the devoted, solitary man of God whose entire life’s work had (alas) saved no one. It was the quintessential line of hopelessness that hovered over this beautiful song of longing.

The Beatles: each one of them added something. (Even Pete, who’d once been a QuarryMan and their mate in the Jacaranda [10]). For several hours, the lads worked together, standing close – shoulder to shoulder, as it were – and in that small bit of time, the fissure closed.

In days to come, Paul would record the song alone, with John and George only brought in to sing harmony. No other contribution needed.

In years to come, they would argue about who had contributed what that seminal night.

Paul would say he had most of the song written before he even visited Kenwood. John would say, “Of course there isn’t a line of theirs [Ringo’s, George’s and Pete’s] in the song because I finally went off into a room with Paul, and we finished the song [11].” Pete would continue to insist that McKenzie was entirely his, but others would deny it vehemently. The Beatles would forget the night they came together as the cleft widened to a split, and they would go their separate ways.

In the summer of 1966, The Beatles lived in a dream, but it wasn’t always a pleasant one. And that night, when they all said, “T’rah” and motored away, John stood at the window, wearing a face that seemed content, yet was anything but. Dousing the light and trudging upstairs did he hum, “All the lonely people, where do they all come from? All the lonely people, where do they all belong?”

It’s possible that he did. And the fissure ran.

1. Rodriguez, Robert. Revolver: How The Beatles Re-Imagined Rock’n’Roll, 132.

2. Of course, Paul famously stated that “Got to Get You Into My Life” was a sly reference to his new fascination with marijuana, but like all Beatles’ songs, “there’s more here than meets the eye.” We’ll discuss the complex levels of meaning in this song soon!

3. Guesdon, Jean-Michel and Phillipe Margotin, All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release, 326.

4. Shotton, Pete, John Lennon: In My Life, 123. Note that Guesdon and Margotin state the Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall were also there. Pete does not include them in his account of the evening.

5. Shotton, 123.

6. Shotton, 123.

7. Shotton, 123 and Rodriguez, 82. Pete says that he was the one consulting the phone book. Rodriguez tells us that Paul was the one consulting the phone book. In any event, a phone book was consulted and the group conferred on last names.

8. Guesdon, Jean-Michel and Phillipe Margotin, All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release, 326. This information was gleaned from David Sheff’s Playboy Interviews with John and Yoko.

9. Shotton, 123.

10. Pete’s contribution might have been quite significant indeed. We are told in Rodriguez’s book that “It was Shotton that came up with the key development of having these two lonely people cross paths, only in death.” (p. 82)

11. Sheff, The Playboy Interviews.

Jude Southerland Kessler is the author of the John Lennon Series: www.johnlennonseries.com

Jude is represented by 910 Public Relations — @910PubRel on Twitter and 910 Public Relations on Facebook.